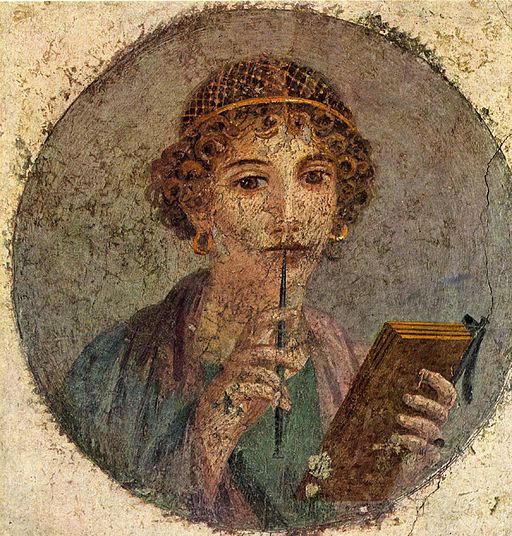

Fresco of Sappho from Pompeii, 1st century CE, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

by Graysen Currie

The narrative of As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner could not exist without the character Addie Bundren – mother of five and wife to Anse. Throughout the chapters of the novel, the narrative’s perspective changes from character to character as they travel to Jefferson to bury Addie’s body. Addie herself has her own chapter – her voice resounding after death to speak her own monologue. By placing As I Lay Dying beside Anne Carson’s translated work of Sappho, If Not, Winter, readers may come to find that Addie may not be truly dead, as vital pieces of her still remain. Many of Sappho’s fragments may even be read from the voice of Addie herself, even before her death. By taking a closer look particularly at Addie’s influence over her sons, the theme of travel, and at Addie’s desire for revenge against Anse, we may see that Addie’s influence is still potent, up until her body is put to rest in Jefferson’s soil.

Addie still lives in the memories of her sons, and in this way drives their actions throughout the novel. While it is well known that Addie isn’t particularly fond of her other sons, she does love Jewel. In her monologue, she describes the moment when she first was pregnant with Cash, when she “knew that living was terrible” (Faulkner 171). Similarly, her reaction to later giving birth to Darl was murderous hatred for Anse. Only with Jewel do soft and delicate descriptions come into being: “With Jewel, I lay by the lamp… Then there was only milk, warm and calm, and I lying calm in the silence…” (Faulkner 176). This love for Jewel may also be reflected in Sappho’s fragments: “If she does not love, soon she will love / even unwilling” (1). Up until this point of the novel, Addie has offered nothing remotely akin to feelings of kindness or compassion for another human, despite being a mother to two already. As a teacher, she showed no inclination for compassion towards children, either, but now with Jewel, Addie finds warmth and serenity. She now has someone to call “my darling one” (Sappho 163). Though she is a mother to her other children, they are not dear to her, and so in loving Jewel, a piece of her comes alive. Addie has become a woman “who loves children more than Gello” (Sappho 168A). Gello are Greek demons who threaten the reproductive cycle of women, and with Addie’s hatred, she may see Anse to be one of these – something who curses her with what she views to be living debt in the form of human lives. However, she finds repose in her affair with Whitfield, and so Jewel, as the production of this affair, exists past Addie’s death to be something she herself lives on in.

Even if Addie does not love her other children, her influence over Darl and Cash continues to keep her alive and present within each chapter of the story. Darl narrates the opening scene of As I Lay Dying as he walks along a path with Jewel. Darl can hear Cash working on Addie’s coffin (“who honoured me / by giving their works” [Sappho 32]) and Darl thinks to himself that “Addie Bundren could not want a better one, a better box to lie in. It will give her confidence and comfort” (Faulkner 5). At the time of this quote, Addie is still alive, but already Addie is speaking through Darl. She also speaks indirectly through Cash, who continues to work on the coffin until its completion. Cash even goes to the effort of giving the coffin a bevelled edge, believing the end result will be a “neater job” (Faulkner 83), and better appreciated, presumably by Addie, despite her passing. As she lies on her deathbed, Cora sees Darl as “he just stood and looked at his dying mother, his heart to full for words” (Faulkner 25). The impact Addie has on Darl continues to affect him throughout the novel, until he acts by burning down a barn with her body inside of it. This once more prompts the voice of Addie through Sappho: “you burn me” (38). Perhaps Darl’s wordlessness was too much, and his heart felt so overfilled for so long that it created the spark so this could affect Addie too. But even so, both Darl and Cash try to keep Addie’s coffin safe from harm. After the coffin is saved from the burning barn, the barn’s owner and Anse both ask Vardaman where Darl is. Vardaman replies that “he is out there under the apple tree with her, lying on her” (Faulkner 225). In a similar scene, Cash lies on top of the coffin too, crying, after rescuing it from the cold clutches of the river. Addie’s sons are acting as if she is alive; as if her body has not perished but instead still holds her essence inside of it: “Then [Cash and others] raise the coffin to their shoulders and turn towards the house. It is light, yet they move slowly; empty, yet they carry it carefully; lifeless, yet they move with hushed precautionary words to one another, speaking of it as though it now slumbered lightly alive, waiting to come awake” (Faulkner 79-80). By having this influence, “she summons her son[s] to “guard her / bridegrooms / kings of cities” (Sappho 164, 161). Though a sickness may have claimed her, Addie is still alive in the memories and minds of Cash and Darl too. And so, “someone will remember [them] / … even in another time” (Sappho 147).

As I Lay Dying is a narrative fundamentally about travel – the journey of the Bundren family and the hardships they face along the way. They take Addie’s body to Jefferson “because [she] prayed this word: I want” (Sappho 22). “[She] might go” (Sappho 182), but only so long as Addie’s family obeys her wishes. Cora doesn’t at first understand why the whole family would struggle through so much for Addie, but because she was adamant about this, the plot that follows blooms into being as they traverse the land. “For she who overcame everyone / left her fine husband / behind and went sailing to Troy. / Not for her children nor her dear parents had she a thought, no – / led her astray” (Sappho 16). By wishing to not lie in the ground with the other Bundrens, Addie leaves her children and husband not only in death (which may be seen as Troy in Sappho’s fragment) but physically too. Addie casts her family out of the country to see if in fact they may “not complete the road” due to the “dewy riverbanks” that all claim are not “crossable” (Sappho 17, 23, 181). After some time, the Bundren family approaches the city of Jefferson. Resting, Darl and Jewel “put her under the apple tree, where the moonlight can dapple the apple tree upon the long slumbering flanks from within which now and then she talks in little trickling bursts of secret and murmurous bubbling” (Faulkner 212). The sounds that they hear from within the coffin are sounds of Addie’s decomposing, since it has taken so long for them to travel to this point. But they take these sounds to mean that she is speaking, and even guess what she’s trying to say. A similar passage rests in Sappho’s fragments: “And in it cold water makes a clear sound through / apple branches with roses the whole place / is shadowed and down from radiant-shaking leaves / sleep comes dropping” (2). In both these passages, nature is speaking: the cold water, and the body that nature has once more claimed as its own. Addie is alive in this way, after the Bundrens have taken days to reach this peaceful place. Both these quotes mention a place of growth and nature, and so through a distant apple tree that Addie has come to lay under, she comes alive once again.

In her own monologue, Addie’s voice more candidly comes to life as she recounts her desire for revenge against Anse. Remembering back to earlier years, Addie says that once she had Darl, she “then believed that [she] would kill Anse. It was as though he had tricked [her]” (Faulkner 172). Anse is a “paingiver” (Sappho 172) for Addie, making her have Cash and Darl. And so Addie plots her revenge. She does not mean to kill him literally – but “[she] long[s] and seek[s] after” a way that “[she] would lead” Anse to his doom (Sappho 36, 172) in a way that he does not even realize it. Then, Addie has Jewel. “And then [Anse] died. He did not know he was dead” (Faulkner 174), because Jewel is not Anse’s. She had tricked him into thinking that she was giving him another child, but Jewel’s father is actually Whitfield. Further in the monologue, concerns over virginity arise in Addie considering her revenge: “I would think: The shape of my body where I used to be a virgin is in the shape of a and I couldn’t think Anse, couldn’t remember Anse. It was not that I could think of myself as no longer unvirigin, because I was three now” (Faulkner 173). Part of Addie’s desire for revenge against Anse manifests in emptying his name of any meaning. And even though Anse has biologically aided in the birth of her children, Addie views them as not his, or even hers, but more than that: smaller parts of herself. “Do I still yearn for my virginity?” (Sappho 170). Addie doesn’t dwell much on this question, as for her, revenge is more important. Addie’s life lives on through Jewel not only as her son, but also as proof of her revenge – and even more so as a smaller part of herself that lasts past the final beat of her heart.

Through her sons, travel, and her desire for revenge, Addie’s vitality shines when illuminated by Sappho’s fragments. With themes of mourning, family, and obligation, As I Lay Dying ultimately concerns itself with what it means to be alive. “Dead, you will lie and never memory of you / will there be nor desire into the aftertime… / you will go your way among dim shapes. Having been breathed out” (Sappho 55).

Works Cited

Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying: The Corrected Text. Vintage International, 1990.

Sappho. If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. Trans. Anne Carson. Vintage Canada, 2003.