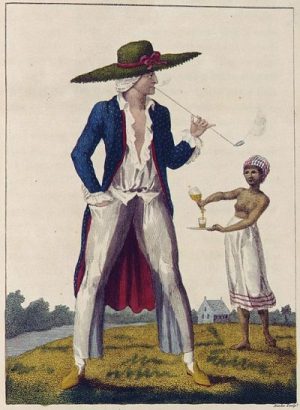

William Blake, A Surinam Planter in his Morning Dress, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

by Madeline Klintworth

David Dabydeen’s Slave Song addresses the dilemma of how to identify the ‘true’ voice of a Guayanese culture that has been clouded and corrupted historically by the voice of colonialism. Dabydeen, born in Guyana to Indian parents but having emigrated with his family to England as a young boy, expresses this conundrum in the three separate voices, all of them created by Dabydeen himself, that are intricately intertwined throughout the book: the creole voice of the poems; the historical, cultural, and at times academic voice of the introduction and notes; and the English voice found in the translation of the creole poems. These voices are, in turn, juxtaposed with the historical colonialist illustrations that accompany the creole poems throughout the book. The complex nature of the culture, and thus the text, forces the reader to constantly re-examine the authority of each given voice. Readers must piece together all they are given and form their own connections in an effort to understand Dabydeen’s attempt to imagine both his homeland and his own identity in relation to it. This is particularly evident in the textual relationships that surround the poem “Brown Skin Girl.” Here, each of the voices represented in the different sections of the book seeks to control or subvert the figure of the Guyanese woman in the text. The colonialist representation of the native woman is mimicked by her own native male counterpart in the poem, and this triangular relationship is then further complicated in Dabydeen’s notes. The glorification of the Western ‘elsewhere’ is seen through the idyllic imagery of the Americas, but is balanced by the dark desperation to escape their reality and home. The woman’s daily life is depicted by her male counterpart as violent, diseased and monotonous. This is delivered without sympathy, perhaps until the end when the speaker reflects upon the suffering behind his dreams for the girl. The only voice we are unable to identify in the work is that of the girl herself, which expresses her lack of control within the conflicting forces of ‘here’ or ‘there’. She is an object of exchange being used by both sides to affirm power over the other. Her character, and its value, does not extend past her bodily identification: “Brown Skin Girl.”

In the introduction to the book, Dabydeen begins by describing his home country in terms of its portrayal in Western literature and media, clearly aware that for many of his readers, these will be the only accessible references to Guyanese culture. Dabydeen foreshadows the frustrations present in “Brown Skin Girl,” where the black female body is used by white men as a means of expressing their own desires, including the shame or indecencies not permitted in “civilization.” Focusing on the tendency to mystify England as a sort of utopia or promised land, with whiteness symbolizing religious purity, Dabydeen explores in the introduction the “banal,” “spiritual” and “sexual” elements of this fantasy: the material gain of “civilization,” the inherent power brought on by whiteness, and the modern sexual appetite centered on the white idealization of the female. At the same time, however, that Dabydeen mercilessly parodies white colonialist attitudes, much of his characterization of the people of his homeland elsewhere in the introduction is far from flattering. His cultural biography of sorts is both gritty and disturbing. He has no qualms about passing judgement on “bush-rum” and its detrimental effects on the Guyanese people, as well as on the sordid reality of wife-beating as commonplace. The daily routines and destructive patterns are made explicitly clear. What is not quite yet entirely clear is a palpable sense of how the combination of invasive and natural forces of domination construct Dabydeen’s worldview, his identity, and his vision of his past.

The reader’s immediate introduction to “Brown Skin Girl” is through the poem itself, which is deceptively simple in its structure and form. The accompanying image seen alongside the poem is a late 18th-century engraving by William Blake of a “Surinam Planter,” whose powerful stance and ornate dress occupy most of the frame. His power over the land, the women, and the depiction of the image itself are explicitly evident. To his right, standing behind him physically and just out of the range of his gaze, is a highly fetishized young black woman. She is standing topless, facing the colonialist and waiting to serve him a drink. Her body, and her service to the man in the image, perfectly complements the thematic content of the poem. As in the text of the poem, in the image the girl is depicted only in terms of what her body can do in service to this figure, who in turn will “save” her from her own identity. The primary source, the original poem, is split into two stanzas which follow a similar pattern to one another. The voice of the speaker both envies and pities the girl. His internalized racism and shame he now projects onto those whom he considers beneath him. It is startling and disturbing for the reader to encounter such Euro-centric statements presented in the creole language. This inherited cultural insecurity presents itself as the speaker urges her to escape and to adopt new ways. To say to the girl, learn to “Taak prappa” (40), is to imply an inherent wrongness in the poem’s very existence, and the existence of what the voice represents. Distinctively human qualities are assigned to the west; it is represented through its technological ‘advancements’. There she will “Laan” (40) to “dress, drive car, / Hold knike and faak in yu haan” and “Move smood, stand tall” (40). The control and order of the west is contrasted to the wild and natural depiction of her home: “De mud, de canal de canefield” (40); “Cackroach, kreketeh, / Maskita na deh- deh” (40). In her home the land represents the power and currency of the culture and is materialized and cultivated. However, in America it is she who will be altered and refined, and will serve as a tool of power in this same way. The poetic content of “Brown Skin Girl” is a voice given to reflect the delusions of elsewhere and the internal and external struggle for power with women’s bodies as currency.

While Dabydeen’s notes exist in theory to clear the reader’s confusion, they serve instead only to add to the complexity of each poem. We are given a rather unique perspective, as his cultural identity seems to defy both popular notions of “native” and “colonialist”. He includes elements of his English scholarly influence (Dabydeen was a lecturer in Caribbean studies at the University of Warwick when he wrote the book) as well as personal and political anecdotes in his notes. However, his personal and emotional biases are also ever-present due to his inevitable closeness to the “voice” he seeks to explore in this collection. There is an implied judgement in his account of Guyanese women who “‘willingly’ give themselves to the white man in a new kind of prostitution. They do so out of a deep feeling of inferiority” (68). On one level, this information is conveyed as a generalized, objective historical fact; on another level, it simultaneously hints at an expression of his own unique personal experience. The reader must again examine how the additional voice in the notes both complicates and complements the poem. The author of the notes seems, at times, to be in agreement with the dehumanizing voice of the speaker: “For the women, this quest for ‘civilization’ can only be realized though giving their bodies: what else have they to offer the white man? What else is he capable of taking from them?” (68) He simultaneously sheds light on the suffering of the women of his home, and minimizes their worth and humanity. Intentionally or not, he describes their bodies in terms of currency between the two male powers, much like the voice of the poem. And there is yet a further context to the historical roots of this ideology. Dabydeen’s “Brown Skin Girl” is an inverted revision of a folk song that originally described a native girl being made worthless and eventually abandoned by the father of her baby seeking new life in the western ‘elsewhere’. Perhaps Dabydeen is intentionally expressing this notion of male inferiority as he describes his own rendition as a “male at the receiving end of such cruel desertion and sexual disdain” (68). It is important to distinguish that even still, the female perspective has been intentionally left out. “Brown Skin Girl” is not a person, but rather a motif for a struggling male ego in a culture in which he must compete for his “rightful” honour, represented in the body of the “Brown Skin Girl.”

The final version of the text given to the reader is the English translation of the poem. Though much of the subtleties of the dialect are surely lost in translation, it certainly assists the average English reader in finding personal connections and deeper meaning within the text. However, it is important for readers to consider which factors may inform their own cultural lens, and how in turn that may affect their worldview as a whole. Unlike the original Creole poem, the English text is structured in sentences, with lines separated clearly on the page. The visual progression of each stanza leads us to two separate conclusions. The first stanza ends with the image of the speaker and a rice bowl, a physical representation of the death of the land “thinking far”(69). It is clear that it is he, and not necessarily the “girl,” who reveres the “manners and material” of the west and longs for an escape. The poem is not about the dynamic between colonialists and Guyanese women, but rather about the projection of the male’s worth onto the figure of the female. The second stanza solidifies this further with the line “Dreams like bleeding deep inside” (69). The last echo of the male speaker’s voice shows how his desires and his suffering intertwine and feed one another. He longs to have his culture’s worth validated through the westernization of “his” women, but the inferiority that such longing brings upon him is at the same time torturous.

Dabydeen’s poetry and its accompanying texts are filled with a variety of voices that must be identified and negotiated by the reader. This complicates immensely both the process of reading and the poetry itself. “Brown Skin Girl,” its English translation, and its notes exemplify how crucial this process is in order to gain a full understanding of the text. The short, repetitive poem is rather straightforward and simplistic upon first glance. This could not be further from the truth, however. Through an examination of its complex interplay of voices, it becomes clear that “Brown Skin Girl” touches on a cultural dynamics of power that extends far beyond a single or singular girl.

Works Cited

Dabydeen, David. Slave Song. Leeds, UK: Pepal Tree Press Ltd, 2005.