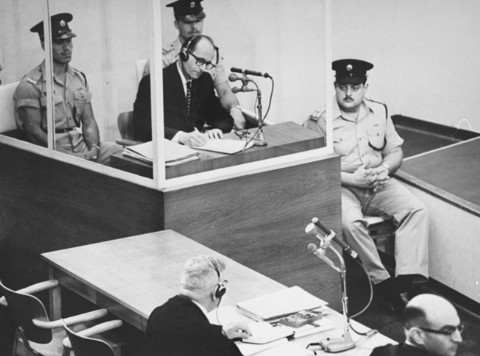

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

by Erfan Hakim

In Plato’s Republic, Thrasymachus makes the disconcerting claim that “justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger” (Plato 338c).What is fascinating about Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil is that Adolf Eichmann falls prey to Thrasymachus’ problematic conception of justice. Not only does Eichmann blindly swallow Hitler’s punitive orders as a deliberate strategy to achieve personal advancement, he does so in an effort to commit himself to justice. It is in this manner that he has no issue “[shipping] millions of men, women, and children to their death with great zeal and meticulous care” (Arendt 25). Likewise, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer also becomes subjected to Thrasymachus’ view of justice when he, in response to the ramifications of the dropping of the atomic bomb, claims that “we, as experts, were doing a job we were asked to do” (Kipphardt 15). Accordingly, both Eichmann and Oppenheimer appear unrepentant for their participation in the organization of mass human destruction. In this paper I will show that while Oppenheimer is eventually able to redeem himself by revealing a sense of remorse for blindly complying with governmental orders (which in turn reveals an implicit love for humanity), Eichmann’s “inability to think from the standpoint of [others]” (Arendt 49), his obsession with social status, and his lack of moral judgment render him indifferent to the brutality of the Holocaust, and enable him to actively abuse humanity without remorse. Thus, I seek to illustrate how Eichmann’s Thrasymachean view of justice — which, I suggest, expresses itself as an absolute commitment to obedience — functions as a foil to Oppenheimer’s conscious and regretful outlook on the ramifications of the dropping of the atomic bomb, as well as his disapproval of the development of the hydrogen bomb. My basic thesis, then, is that Eichmann’s unequivocal belief that just action is obedience to the law of one’s state (Plato 339b) fosters tribalism and traps him inside of an ideological group that is not only rooted in terror, but occludes his social obligations. In this way, I demonstrate that the figure of Oppenheimer offers a critique of, as well as an alternative to, Eichmann’s flawed moral reasoning. In deviating from a Thrasymachean conception of justice, Oppenheimer enters a Socratic domain that puts the collective good into the foreground. While this leads him being exiled from his own ideological group, I argue that this sacrifice is precisely what enables Oppenheimer to rise above Eichmann’s deplorable behaviour and transcend ideology. By embodying the Socratic notion that one’s loyalty ought to be directed to humanity, rather than to any particular ideological group, Oppenheimer overcomes Eichmann’s conformity and encourages humanism.

In Plato’s Republic, the character of Thrasymachus presents a compelling and, simultaneously, unsettling argument for the true nature of just or right action when he claims that “justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger” (Plato 338c). Although his position is malleable, and undergoes minor modifications throughout the first book of the Republic (which is a natural consequence of Socrates’ relentless interrogation), the essence of Thrasymachus’ argument is that “each [ruler] makes laws to its own advantage […] and they declare what they have made — what is to their own advantage — to be just for their subjects, and they punish anyone who goes against this as lawless and unjust” (Plato 338e).GeorgeHourani understands this as suggesting that Thrasymachus is advocating for a form of legalism. According to this interpretation, Thrasymachus is a relativist who denies that justice is anything beyond obedience to existing laws (Hourani 110). Indeed, Socrates, in cross questioning Thrasymachus, makes it clear that he understands obedience to law as being one of the basic definitions offered by Thrasymachus: “Tell me, don’t you also say that it is just to obey the rulers?” (Plato 339b). While Socrates’ chief concern is to elicit a fundamental contradiction in Thrasymachus’ thinking, namely, that rulers are infallible, Thrasymachus retaliates by suggesting that a “ruler, insofar as he is a ruler, never makes errors and unerringly declares what is best for himself, and this his subject must do” (Plato 341a).

In Eichmann in Jerusalem, Adolf Eichmann consciously subjects himself to this view of justice; Arendt writes that “[Eichmann] had always been a law-abiding citizen, because Hitler’s orders, which had certainly been executed to the best of his abilities, had possessed the “force of law” in the Third Reich,” and that the “command of the Führer […] is the absolute centre of the present legal order” (Arendt 24). In other words, given Hitler’s categorical position of dominance in Nazi Germany, he is able to determine justice by ordering the deaths of millions of Jews, and Eichmann — in raising his words to a state of divinity — makes it his life’s mission to commit himself to this questionable notion of justice by arbitrarily following through with Hitler’s morally corrupt demands. Arendt’s claim that “he would have had a bad conscience only if he had not done what he had been ordered to do” (Arendt 25), and her suggestion that “he would have killed his own father if he had received an order to that effect” (Arendt 22) corroborates the view that Eichmann would have been more than willing to overstep boundaries so as not to disobey the laws of the state. But, even more than that, it indicates that such behaviour will inevitably preclude the possibility of essential human values like empathy and compassion. Indeed, Corduwener emphasizes that Eichmann became “incapable of human compassion” (Corduwener 143), and relates this decay of moral values to the fact that “[he] would have followed every [command] or order of any political leadership […] even while he knew that the orders were wrong” (Corduwener 139). Thus, justice, for both Eichmann and Thrasymachus, is a matter of conformity, and of obliging the firmly held beliefs of one’s superiors, regardless of whether or not their decisions are tyrannical. While Thrasymachus’s conception of justice intends to organize the whole of humankind into a systematic social structure that is supposed to enable ‘order’— as is illustrated in the authoritarian regime of Nazi Germany — it is worth noting that the obstinate obligation to obedience that this social structure demands has severe limitations and dangers. Not only does it occlude one’s cognitive autonomy (i.e. the capacity to think for oneself), it also ensures “that all other questions of seemingly greater import — of ‘How could it happen?’ and ‘Why did it happen?,’ of ‘Why the Jews’ and ‘Why the Germans’ etc. — be left in abeyance” (Arendt 5).

Likewise, Oppenheimer also appears to be subsumed by Thrasymachus’ view of justice — which, as I have shown, demands a vehement tendency to obedience — when he responds to Robb’s accusation of his “[support] of the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan” by suggesting that he was simply “doing [his] job” (Kipphardt 13), and that “we, as experts, were doing [what] we were asked to do” (15). Like Eichmann, Oppenheimer emerges as a man who is forced to compromise his integrity in an effort to execute the orders demanded of him. For both Eichmann and Oppenheimer, the question of human suffering appears to be left out of the equation so long as they were following their orders. At first glance, this comes across as an innocuous defence. Neither Oppenheimer nor Eichmann functioned as the evil geniuses behind such morally questionable political decisions. Why, then, should they be forced to bear full responsibility? Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that while it is true that neither Oppenheimer nor Eichmann directly advocated for the political decisions that occurred within their respective contexts, both figures consciously played instrumental roles in the organization of genuine human destruction, which reveals a disturbing diversion from any system of moral and ethical values. In the case of Eichmann, he “supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations” (Arendt 279); in the case of Oppenheimer, he knew that the “dropping of the atomic bomb on the target [he] had selected would kill thousands of civilians” (Kipphardt 15). For this reason, the fundamental problem associated with Thrasymachus’ view of justice is that it reduces the individual to a machine-like being who is unable to distinguish between right and wrong, or good and evil. Eichmann’s indication that when “‘The Führer ordered the physical extermination of the Jews’ […] I understood, and didn’t say anything, because there was nothing to be said” (Arendt 83) reveals the necessity of suppressing one’s moral judgement so as not to undermine those in positions of dominance, even if they happen to be legislating unjust laws. Oppenheimer, likewise, echoes this view when he notes that “in every case, I have given my undivided loyalty to my government, without losing my uneasiness or losing my scruples” (Kipphardt 78). In other words, in dogmatically committing themselves to a Thrasymachean view of justice, both Eichmann and Oppenheimer have convinced themselves that their sole object of life is to reinforce prevailing — not to mention, unequal — power structures within society. Hence, they become blinded to the moral ramifications of their deeds.

Nevertheless, whereas Eichmann remains impervious to the consequences of his actions, Oppenheimer’s confession that he possessed “terrible moral scruples” (Kipphardt 15) reveals an underlying sense of remorse and regret concerning his participation in the tragedy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Richard Ball’s remark that “[Oppenheimer] ends haunted with guilt, both for betraying friends, colleagues and lovers, and for masterminding the most destructive weapons ever made” (Ball 301) illustrates Oppenheimer’s burgeoning sense of self-consciousness and awareness in relation to the atrocious consequences of his deeds. It is in this way that Oppenheimer begins to recognize that his purpose ought to transcend simply buttressing existing power dynamics within society, and to embody the Socratic method of challenging the norms and conventions of those unequal power dynamics, in order to endorse the collective good. His query that “I ask myself whether we, the physicists, have not sometimes given too great, too indiscriminate loyalty to our governments, against our better judgement (Kipphardt 126-27) reveals the necessity of withdrawing from Thrasymachus’s view that justice is obedience to the decree of one’s superiors, for it denies a fundamental aspect of what it means to be living as a human being on this planet: the maintenance of independence and free will. This profound realization is evidenced in his comment that:

When, more than a month ago, I sat for the first time on this old sofa I felt I wanted to defend myself for I was not aware of any guilt, and I regarded myself as the victim of a terrible political conjunction. But when I was being forced into that disagreeable recapitulation of my life, my motives, my inner conflicts, and even the absence of certain conflicts — my attitude began to change. (Kipphardt 125)

While it is true that this new realization of his convoluted role as the architect of weapons of mass destruction may have come too late in that the destruction had already taken place, it is nevertheless worth mentioning that Oppenheimer’s feelings of remorse give him at least partial redemption from his offences. Such a change of attitude guarantees that he has made the conscious decision to never partake in such destructive activities again, which is illustrated in Oppenheimer’s eventual resignation from the General Advisory Committee as soon as he became aware of the fact that the president, despite his ongoing disapproval, still went forward with the crash program for the hydrogen bomb. He writes, for instance, that “I offered to resign from the General Advisory Committee,” because, as Oppenheimer went on to say, “a man must take the consequences when he has been overruled by a crucial issue” (Kipphardt 80).

Eichmann’s “inability to ever look at anything from the other fellow’s point of view” (Arendt 48), in contrast, reveals an empathetic void that authorizes him to slumber on the criminal gravity of his deeds, leaving him content with the way in which he chooses to conduct himself in the world. Arendt’s assertion, for example, that “the longer one listened to him, the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, from the standpoint of somebody else” (Arendt 49) relates Eichmann’s monstrous activities to his failure to scrutinize the justification of the rules and conventions that he so eagerly accepts. As Socrates would have likely pointed out: “he was full of opinions (doxai) he took to be true without question” (Beatty 268). Therefore, Arendt attributes Eichmann’s ‘evil’ not to intrinsic cruelty or disgust of the Jewish people, but simply to his inability or his refusal to think for himself. Indeed, Thrasymachus’ authoritarian view of justice encourages, and even demands, Eichmann’s thoughtlessness, for it is thoughtlessness that can be most easily manipulated into serving the “advantages of the stronger.” Crucially, the Socratic method of constant interrogation and questioning is not compatible with Thrasymachus’ view of justice, for the simple reason that such a philosophical approach will undermine, and indubitably lead to the collapse of, the more ‘powerful.’ However, whereas Oppenheimer “takes the consequences” of entering this Socratic domain by disapproving the development of the hydrogen bomb, and regarding the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as calamitous missteps — which is depicted in his claim that “the great discoveries of modern science have been put to horrible use” (Kipphardt 15) — Eichmann’s blind obedience to the law of Hitler’s land embeds him inside of a resentful ideological group that inhibits his capacity to recognize that “murder is against the normal desires and inclinations of most people” (Arendt 150).

While Oppenheimer persistently challenges his “undivided loyalty to [his] government” by wondering “whether [they] were not traitors to the spirit of science” (Kipphardt 126), Eichmann, in not questioning Hitler’s vindictive laws, traps himself inside of a belligerent ideology that fosters cultural tribalism. Arendt’s remark that “his conscience rebelled not at the idea of murder but at the idea of German Jews being murdered,” and that “this sort of conscience, which, if it rebelled at all, rebelled at murder of people ‘from our own cultural milieu’” (Arendt 96) illustrates the way in which Nazi ideology has eliminated in Eichmann any “connection with the real world as it is constituted by human plurality” (Mack 42). As Mack points out: “Eichmann sees the outside world in terms of the uniformity of Nazi racism, which, by killing those who perceived to be other, destroys human diversity” (Mack 42). That is, Eichmann’s capacity to commit mass murder is an outcome of his retreating from the communal sphere, and his failure to recognize that human beings belong to the same species, and are hence sufficiently alike in their capacities to understand one another. As Arendt identifies inThe Origins of Totalitarianism, “‘tribalism’ and ‘racism’ are very realistic [and] very destructive ways of escaping the predicament of common responsibility” (Mack 58). Therefore, the preeminent consequence of Eichmann’s Thrasymachean conception of justice hinges on the fact that it compels him to view social obligation as something irrelevant and worthless. Conversely, Eichmann is rewarded for making sure that his primary obligation remains as loyalty to his group or to those who are strongerthan he is. Rather than trying to establish truth, or move towards a reasonable approximation of reality, the fundamental objective of Eichmann’s ideological group is to structure social interactions such that his own fascist group comes out on top. In attributing unearned moral superiority to his own cultural group, Eichmann and his fellow Nazis were not only able to eradicate those who possessed different racial, ethnic and sexual characteristics than them, but in so doing they managed to reduce themselves to a state of passivity. The peculiarity of Thrasymachus’ view of justice is that it reduces the individual to the state of a passive subject: he is subjected to the will of either a group or a supposedly stronger ruler. In authorizing the resignation of his own individuality, Eichmann chooses to forever remain a slave.

It is in this fashion that Oppenheimer’s thoughtfulness, with regard to the moral implications of his work, functions as a foil to the unexamined life of Eichmann. Whereas Eichmann only sees the world through the lens of his ideological group, Oppenheimer — in recognizing the problem of “[handing] over the results of [their] research to the military, without considering the consequences (Kipphardt 126) — acknowledges the injustice that one can commit by arbitrarily complying with governmental orders. In emphasizing the importance of “considering the consequences” of his deeds, Oppenheimer places the human race at the position of paramount importance. Even more, it is here that Oppenheimer begins to learn a fundamental

Socratic feature: the ability to ask questions that foster doubt. In the words of Audra Wolfe, “[Oppenheimer] was beginning to question the propriety of dedicating [his] work to national interests rather than to the nation of science” (Wolfe 14). It is worth noting that Socrates was not executed for his seemingly flamboyant and presumptuous suggestions, but for tenaciously doubting the absolute truths of others (Schultz 711). Similarly, in declaring that “we were doing the work of the devil,” (Kipphardt 127),Oppenheimer is cast out of his own ideological group: “We conclude that Dr. Oppenheimer can no longer claim the unreserved confidence of the government of the Atomic Committee Commission” (Kipphardt 124). Nevertheless, it is precisely this exclusion that enables Oppenheimer to retreat back into the communal sphere, and demonstrate his love for humanity. While Eichmann only looks to the interest of his own cultural group, Oppenheimer broadens his scope by focusing on the long-term and wider picture of the collective good. As Socrates points out in The Apology: “if you think that a man who is any good at all should take into account the risk of life or death; he should look to this only in his actions, whether what he does is right or wrong, whether he is acting like a good or a bad man” (Apology28b). The crux of Socrates’ statement is that one’s obligation to humanity surpasses the obligation one has to either his group or to his superiors. While Oppenheimer may have committed “something like ideological treason” (Kipphardt 126) by opposing the development of the hydrogen bomb, he is at the same time advocating for “humanist values such as openness in American politics and communalism in global relations” (Banco 136). In the end, exclusion from one’s ideological group is irrelevant, because in embracing such an exclusion you open the doors to the most important group of all: the human race. Whereas Oppenheimer overcomes the conformity that Thrasymachus demands of his subject, Eichmann’s passivity ensures that he remains an isolated follower.

Both Eichmann and Oppenheimer appear to fall at the mercy of Thrasymachus’

dangerous notion of justice, namely, that it is just to obey the rules of one’s superiors, even if those rules end up having severe moral ramifications. Nevertheless, while Oppenheimer manages to break away from this notion of justice, Eichmann’s “inability to think” and his desire for personal advancement encourages him to pursue the Thrasymachean path until his last breath. The consequences of such an attitude places Eichmann inside of a cultural group that not only encourages him to be responsible for millions of deaths, but blinds him from his social obligations. Oppenheimer’s progression into a Socratic domain, on the other hand, provides him with the much-needed empathy that is required to redeem himself from his initial negligence of humanity. While this led to him being cast out of his own ideological group, this exclusion is exactly what enabled him to become more conscious of humanity’s needs. The message that Arendt is trying to elucidate, and the message that is embodied in the character of Oppenheimer, is that in a world filled with conformists, what humanity needs, above all, is healthy disobedience. That is, to make sure that history does not end up repeating itself (and history has a funny way of coming back to haunt us), what we need to do is begin exercising our rights as citizens — our Socratic rights — to criticize, to reject conformity, passivity and inevitability, to develop a life-long commitment to asking questions. While Oppenheimer eventually embodied these values, Eichmann refused to do so and, as a consequence, he was responsible for the deaths of millions of human beings. Let us not make the same deceptively simple mistake. At the centre of this idea is taking the human for what the human is, and a belief that it is worth trying to do better.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Penguin Group, 2006.

Beatty, Joseph. “Thinking and Moral Considerations: Socrates and Arendt’s Eichmann.” The Journal of Value Inquiry, vol. 10, no. 4, 1976, pp. 266–278. doi:10.1007/bf00137306.

Ball, Philip. “Theatre: Atomic Tragedian.” Nature, vol. 518, no. 7539, 2015, pp. 301–301.doi:10.1038/518301a.

Banco, Lindsey Michael. “Presenting Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer: Science, the Atomic Bomb, and Cold War Television.” Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 45, no. 3, 2017,

- 128–138. doi:10.1080/01956051.2016.1269052.

Corduwener, Pepijn. “‘Eichmann Is My Father’: Harry Mulisch, the Eichmann Trial and the Question of Guilt.” Journal of War & Culture Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 133– 146. doi:10.1179/1752627214z.00000000039.

Hourani, George F. “Thrasymachus’ Definition of Justice in Plato’s Republic.” Phronesis, vol. 7, no. 1-2, 1962, pp. 110–120. doi:10.1163/156852862×00070.

Kipphardt, Heinar. In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Translated by Ruth Speirs, Hill and Wang 1997.

Mack, Michael. “The Holocaust and Hannah Arendt’s Philosophical Critique of Philosophy:

Eichmann in Jerusalem.” New German Critique, vol. 36, no. 1, 2009, pp. 35–60. doi: 10.1215/0094033x-2008-020.

Plato.Apology. Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy: from Thales to Aristotle. 2nded., translated by G.M.A. Grube, Hackett Publishing, 2000, pp. 112-130.

Plato. Republic. Translated by G.M.A. Grube, edited by C.D.C Reeve, Hackett Publishing, 1992.

Schultz, Anne-Marie. “Socrates as Public Philosopher: A Model of Informed Democratic Engagement.” The European Legacy, vol. 24, no. 7-8, 2019, pp. 710–723. doi: 10.1080/10848770.2019.1641312.

Wolfe, Audra J. Competing with the Soviets: Science, Technology, and the State in Cold War America. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2013.