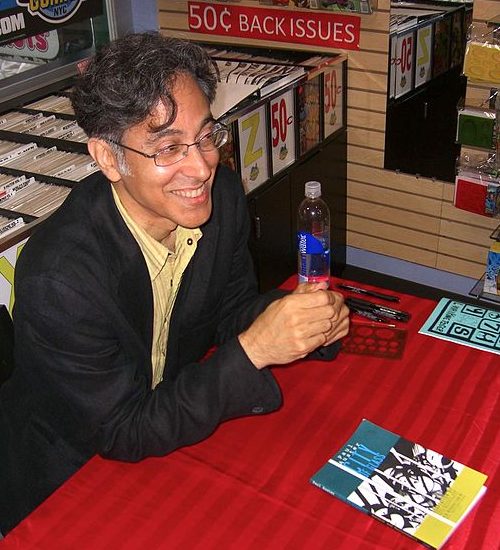

David Mazzucchelli, by Luigi Novi, licensed CC BY 3.0. (c) Luigi Novi/Wikimedia Commons

by Serena Huang

Paul Auster’s novel, City of Glass, fabricates a world in which appearances often fail to correspond to reality and the readers can be as confused and bewildered as the characters in the novel. To adapt City of Glass into a graphic novel, where images on every panel supplement a significantly-reduced amount of text, constitutes a considerable challenge. In Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli’s graphic novel retelling of the story, the plot, characters, and setting essentially remain the same as in the original text version, but the approach used to describe the protagonist, Quinn, and his attempts to solve a case differs noticeably due to the additional range of storytelling tools that the graphic novel provides. This essay examines the ways in which the graphic novel is either more effective or less effective in its message compared to the original text, as well as the specific features, such as the usage of panels, perspectives, and visual detail, which contribute to differences between the texts.

One of the most pivotal scenes in the story occurs in the Grand Central Station in New York City, as the events of this scene determine much of the course of the remainder of the novel. It is interesting to note that while the original text is approximately two hundred pages long and the graphic novel adaptation is a little over half its length, both versions devote around ten pages to this scene, which suggests that the adaptation cannot always omit or condense details from an original text. In the beginning of the scene, the author of the original, written text introduces the train station in which Quinn finds himself. Although the graphic novel adaptation does so as well with an abundant amount of visual detail in its long, horizontal panels, the first page only includes two captions’ worth of text, which leaves the reader to infer the remainder of the details from the images alone. For example, the text directly reveals to the reader that “[Quinn] saw by the clock that it was just past four” (Auster, page 81). In the adaption, however, a careful reader must pay attention to the visual detail to locate the clock in the background, located halfway in between Quinn and the border of the panel, on which the hour hand and minute hand indicate that it is approximately five minutes past four (Karasik, page 46). It can be easy to miss the clock, especially given that Quinn faces away from it in such a crowded panel, which implies that, on the whole, a graphic novel cannot lay out all the details as neatly and as clearly as the original text can.

As Quinn continues to move through Grand Central Station, the graphic novel provides an instance in which it is better equipped to convey the nuances and subtleties of the author’s message. In the original text, the reader learns of the effects on Quinn of taking the name of Paul Auster and the comfort and freedom which come with the illusion. The tone generally remains consistent throughout the passage of text, as if it is meant simply to convey the information to the reader. The graphic novel adaptation, however, adds a tangible sense of sudden drama, as within three panels, the point of view zooms in on Quinn to focus on his face (Karasik, page 47). As it is successively enlarged in the three panels, it shifts from his normal appearance to that of a determined, resolute, and fedora-wearing detective, drawn in solid black lines and surrounded by thick lines of emphasis which almost give the impression that a bright light emanates momentarily around him, in stark contrast to the dark backgrounds of the previous two panels. According to the thought bubble in the first panel, Quinn assumes the appearance of Paul Auster, but since the character of Paul Auster has not yet made an appearance in the story, neither Quinn nor the reader truly knows what Paul Auster looks like. Therefore, Quinn must choose another character with whom he is more familiar, and his appearance in the third panel bears a striking resemblance to Max Work, the narrator of Quinn’s own mystery novels, who is introduced in the beginning of the novel (Karasik, page 3). This sequence of panels implies that while Quinn wants to imagine himself as Paul Auster, he actually steps into the role of Max Work, as if living out one of his own detective stories.

In other parts of the Grand Central Station scene, however, the graphic novel adaptation cannot convey the wealth of detail present in the original novel, especially where it concerns the inner thoughts of the characters. When Quinn encounters the young woman reading the book that he wrote, the text reveals Quinn’s expectations for his encounter with one of his readers and describes how he wants to be “suavely diffident” and show “great reluctance and modesty” (Auster, page 85). When the bubble-gum-chewing reader does not live up to his expectations, however, Quinn reacts with indignation and annoyance and wants to “tear the book out of [the woman’s] hands and run across the station with it” (Auster, page 85). In the graphic novel adaptation, this encounter takes place over nine, uniform panels on a single page, which greatly reduces the amount of attention given to Quinn’s expectations and thoughts (Karasik, page 49). Quinn is portrayed as merely surprised in the first panel when he glimpses the cover of the book, and his inner desires, whether positive or negative, are inaccessible to the reader of the graphic novel. His expression in the last couple of panels is clearly frustrated or annoyed, but his downturned eyebrows and firmly-set mouth cannot show the level of precision present in the text as Quinn “[struggles] desperately to swallow his pride” and restrain the urge to “punch the girl in the face” (Auster, page 87).

Another way in which the graphic novel fails to convey the entire spectrum of details occurs as a result of the medium of the work. Notably, the adaptation by Karasik and Mazzucchelli is rendered in black-and-white, which means that it loses all the vivid colour described in the original text. A sea of passengers surges towards Quinn as he waits by the train, and Auster describes them as “men in brown and gray and blue and green, [and] women in red and white and yellow and pink” (Auster, page 88). In the graphic novel, all the colours are reduced to either black or white, leaving the reader with the task of determining which colour a passenger’s clothing is likely to be. Furthermore, the original text describes the sheer diversity of the passengers who come from every imaginable background, as if the crowd really is vast and limitless in its size, but in the graphic novel, the artists can only draw so many distinct figures due to the limitations of space on the physical page and the width of the pen strokes. In this way, the original text version has an advantage because of its ability to appeal to the reader’s imagination, whereas the graphic novel is restricted by the nature of its images, which insist that the graphic novel has to explicitly lay out the scene for the readers.

One panel in particular highlights the differences between the original text and the graphic novel adaptation, although it perhaps cannot even be considered a panel as it has no borders, almost as if to suggest that this scene’s importance to the story cannot be contained. Quinn finds himself conflicted between following either the first or second Stillman, who walk off in opposite directions, and the graphic novel artists convey the crucial decision that Quinn must make through the layout and perspective of the panel (Karasik, page 53). The only three figures present are the two Stillmans, who take up the majority of the space, as well as Quinn, standing stupefied in the background. By completely removing the rest of the background, the graphic novel artists draw the reader’s attention to the three characters alone, without any distractions present at all from the rest of the crowded train station — it is as if Quinn’s attention is so focused on the two walking Stillmans that the train station literally disappears. Furthermore, the use of perspective and the placement of the Stillmans directly in the foreground give the impression that the two Stillmans are on the verge of walking off the physical page, perhaps out of the book altogether, while Quinn is still stuck helplessly at the back of the page. The original text, on the other hand, cannot reproduce the effect of a disappearing background or a shift in perspective, and all it can tell the reader of Quinn’s struggles is that he craves the body of an amoeba so that he can pursue two different Stillmans in two different directions (Auster, page 90). In this way, the text lacks the richness and possibility of the graphic novel adaptation, as well as its ability to make such an important moment stand out for the reader.

Overall, as both text novels and graphic novels have their strengths and weaknesses, neither one nor the other is necessarily superior, but adapting a novel into a graphic novel results in the addition of emphasis to some areas as well as a decrease in details in other areas. Graphic novel artists have at their disposal the tools necessary for including a large number of details within the relatively-limited space of one panel or for adding drama and intensity to a particular scene. At the same time, graphic novels cannot include every meticulous detail which occurs in the original novel, and due to lack of space must omit many of the characters’ inner thoughts. Thus, the narrative which the graphic novel tells is not an exact copy of the original novel, but permits the reader to choose from two different approaches to the same story.

Bibliography

Auster, Paul (1987). City of Glass. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Penguin.

Karasik, Paul, David Mazzucchelli, and Paul Auster (2004). City of Glass. New York: Picador/Henry Holt.