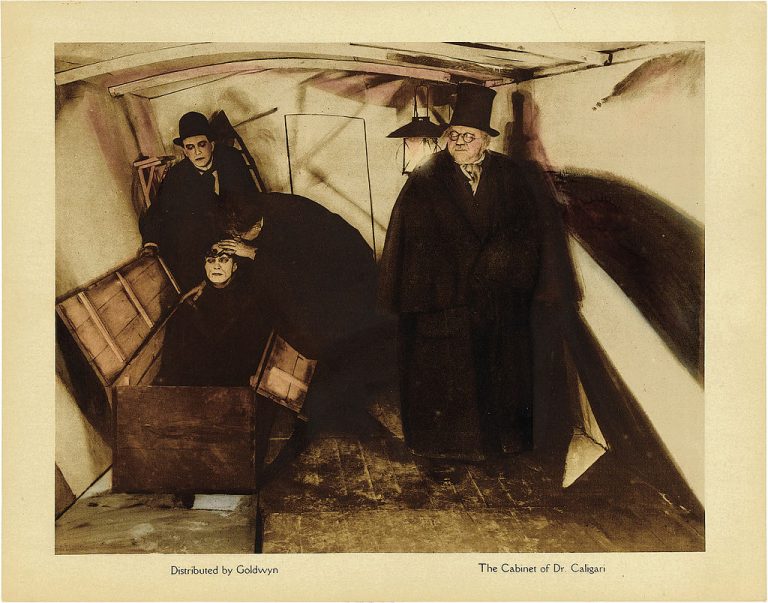

Lobby Card for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

By Aaron Zhuo

May 2017

“Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass”

— Anton Chekhov

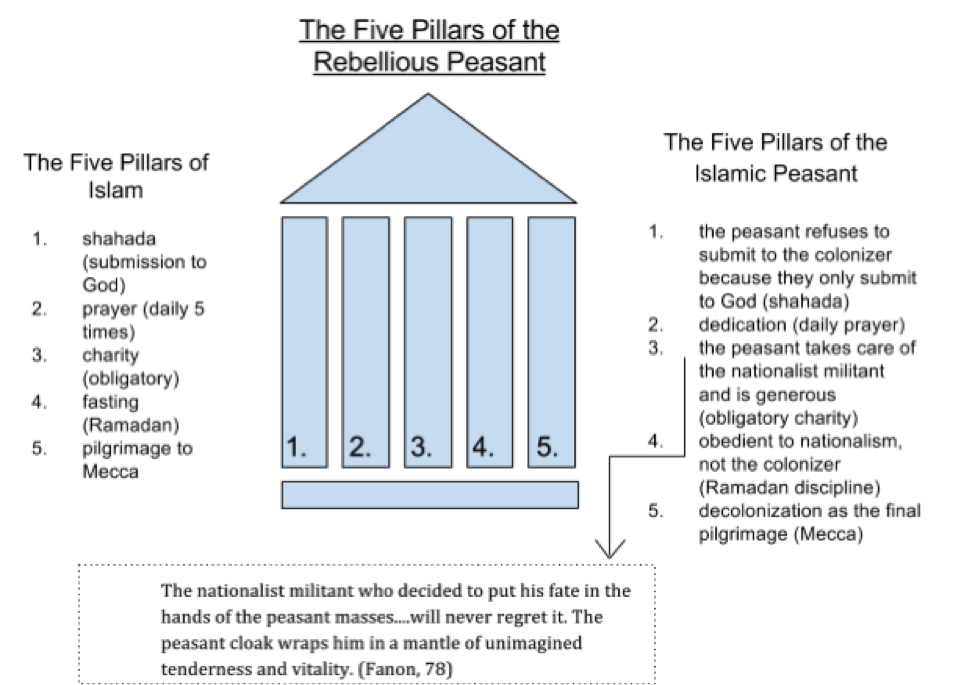

Chekhov’s concept of ‘showing not telling’ continues to pervade both film and text today. Whereas contemporary films have access to dialogue as a medium of communication between director and audience, silent films instead heavily rely on visual expression as a means of communication. The way that Robert Wiene’s 1920 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari utilizes expression by using images to give meaning through mise en scène[1] is perhaps one of the reasons the film is so highly acclaimed to this day and remains one of the cornerstones of cinema. This essay however, will specifically only focus on the use of composition to demonstrate the way that Wiene ‘shows’ as opposed to ‘tells’ meaning. In particular, the essay will explore the effect of the iris shot, camera proxemics and negative space as compositional techniques to direct attention towards the characters and create meaning through a focus on emotion. Furthermore, a secondary, seemingly contrasting function of negative space will be analyzed, along with how it accentuates the externalized emotion fear, which is represented by the abstract set design. Moreover, the claustrophobia created through a prevalent deviation of the proscenium arch will be explored to reveal the way it reinforces the theme of fear. Whereas the compositional techniques work towards emphasizing the internal representation of emotion through characters, these techniques interestingly also work towards emphasizing the external representation of fear through the set design. The meaning created through this dichotomy between focus on character and set design will be discussed with reference to the 1920s movement German expressionism and how it relates to Wiene’s creation of meaning in the theme of duality.

Wiene utilizes the Iris shot and camera proxemics to manipulate attention towards the characters and accentuate the visual expression of character emotions. The Iris shot refers to a transitioning shot where a black circle shrinks towards a point on the screen, or moves outwards from a point on the screen. Similar to the use of depth of field, the shot can be used to minimize distractions from the surroundings and focus the viewer’s attention towards a character or object. Wiene most noticeably uses the iris shot to emphasize what the characters are feeling, thereby foregoing the need for dialogue through intertitles. In one example between the busy town clerk and Caligari, the scene interchanges back and forth between a long shot of both the town clerk and Caligari to a mid shot of Caligari. The control over camera proxemics, which refers to the proximity of the camera from the characters, has varying effects on the audience, especially when two different shots that garner different responses are placed next to each other. Film critic Louis D. Giannetti suggests that there is a positive correlation between camera proximity and emotional impact. By applying this correlation, the increased proximity of the camera from long shot to mid shot actually serves to accentuate emotion. Moreover, the iris shot that is masked over the mid shot furthers this impact by highlighting the changes in Caligari’s facial expression. The iris shot often inadvertently makes use of negative space, enhancing its ability to manipulate attention to the characters.

What then, is the function of negative space? Negative space refers to the area around the main subject of the image and accentuates focus on the main subject of the shot or photograph. This manipulation of the audience’s eyes allows Wiene to more clearly portray the actions and emotions of characters. This becomes particularly important as dialogue is restricted in silent film, placing a greater importance on action and emotion. Cinematographer Willy Hameister utilizes negative space in Caligari by creating completely black areas of the screen. Both figure 1B, figure 2A and figure 2B showcase the use of negative space in attracting viewer attention. Whereas figure 1B is shot in a way that shows Caligari fidgeting impatiently with his hands, figure 2A and 2B zoom in to a close-up, playing on camera proxemics and allowing the viewer full access to the details on Alan and Cesare’s faces. The pitch black areas of the screen are of little to no visual interest, thus diverting the viewer’s attention away from the negative space to the well lit areas of the screen. As highlighted by the use of the iris shot, negative space often directs the audience’s attention towards the characters, thus aiding in revealing character emotion.

Fig. 3B: Negative space is manipulated so that light guides the eye towards the claustrophobic alleyways (Baxter)

The use of negative space however, is not confined only to the iris shot. The technique is in fact prevalent throughout the film, arguably in every single shot. Whereas Hameister uses negative space to attract viewer attention to the characters through the iris shot, his careful manipulation of the technique gives it a secondary function – diverting attention away from the characters and towards the set design. Although this seems contrary to the functions of camera proxemics and the iris shot as discussed above, it is yet another way that Wiene creates meaning through visual symbolism. The secondary function of negative space exists in directing attention towards the set design to emphasize one of the dominant themes in German expressionism – fear. German expressionism is characterized by the way that filmmakers externalize “human emotion and desire” (Ahi). This externalization of emotion – in Caligari, fear – is represented by the claustrophobic and abstract set design emphasized partly through the use of negative space. As mentioned previously, negative space often diverts the viewer’s eye from areas of darkness to areas of light. The use of negative space in the foreground of figure 3A is evident – when the viewer’s eye lands in the foreground, they are directed towards the man in the middle because he is standing in a very well lit area of the stage. When the viewer’s line of sight falls anywhere behind him however, the eye may instead begin to follow the light into the claustrophobic hallways behind and to the right of the man. The fact that the eyes are still attracted to the alleyways in figure 3B emphasizes how powerful the stage is as an externalization of fear, a character in itself. Crucially, Hameister’s stylistic decision to guide the eye into claustrophobic hallways through the use of negative space brings attention towards the set, subsequently adding to the theme of fear.

Wiene also consciously deviates from the proscenium arch in order to visually depict claustrophobia and thus the theme of fear. Originating from theatre, the proscenium arch refers to the “frame” where actors would perform – in other words, it was the frame of the stage itself. The “proscenium arch” of film may then refer to the screen itself, as all the actors similarly perform within it. In Caligari however, Hameister distorts and warps the frame in order to create a sense of claustrophobia. Although this is evident from the use of the iris shot, figure 4A shows another perhaps more subtle usage of this contortion of the frame. This scene of Cesare being chased after attempting to kidnap Jane only fills about half the available space on the screen. In addition to this, the edges and especially the bottom of the scene are almost enveloped in darkness, with shadows seemingly encroaching into the scene. As opposed to using an iris shot with its concrete geometric shape, ominous streaks of darkness creep onto the screen as a result of the deviation from the proscenium arch. This visual expression of claustrophobia may not seem obvious at first, but the prevalence of it throughout the film creates a constant and unnerving feeling of fear.

The theme of fear is also accompanied by the theme of duality, which is emphasized through the contrast between the adherence and deviation of the proscenium arch. Ahi and Karaoghlanian suggest that German expressionist films explore “paranoia, fear, and schizophrenia” where the schizophrenia is represented through the theme of duality. Figure 4A shows Cesare’s attempt to kidnap Jane whilst the next scene in figure 4B presents Jane safely recovered. The progression from the claustrophobic framing to the more relaxed framing shows how Hameister uses two very different and possibly opposite framing styles in order to convey a change in emotion. In this way, Wiene and Hameister “show” emotion through utilizing the frame and proscenium arch in order to visually represent the fear that Jane is being kidnapped in figure 4A and the relief that she is recovered in figure 4B.

The theme of duality is most remarkably encompassed through the dual functions of negative space, where the conflict between the internal emotion and external representation of emotion create an uncomfortable pull on the viewer. Importantly, the theme further reinforces one of the main traits of German Expressionism – schizophrenia. Why did Wiene not focus on the characters alone, as opposed to both the characters and the set design? Although lack of budget may have been a reason, the extended emphasis on the geometric abstractness of the set design may have been indicative of there being a purpose behind diverting attention towards it. One interpretation is that both the character and set design demand the viewer’s attention. This pull from both creates an uncertainty as to where the viewer should actually look. In figure 3A, the manipulation of negative space results in both the man and the right alleyway demanding viewer attention. In a more subtle example, Figure 5 depicts Francis, completely bathed in light. Yet it seems somehow inevitable that the eyes follow the abstract shapes and stream of light behind him up the staircase and into the darkness. The duality between pulling attention towards the internal representation of emotion shown by character Francis and external representation of emotion through set design is the basis of the sense of discomfort.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari conveys themes of fear and duality from German expressionism by manipulating compositional techniques to show instead of tell. Perhaps what makes Wiene and Hameister’s Caligari a magnum opus of visual storytelling lies in its mastery over its techniques. In Forbes magazine, Rob Reid suggests that when a new medium grows, “content evolves in directions that its earliest pioneers could not have foreseen” (Thier). One may wonder if this content is evolving too far and too quickly. With contemporary films having only a little under a century of access to synchronized dialogue under their belt, perhaps the directors of today should focus on mastering what they have already as opposed to delving into future technologies or even mediums.

Works Cited

Ahi, Mehruss Jon, and Armen Karaoghlanian. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).” Interiors. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Jan. 2017.

Baxter, Marttin. “Classic & Influential: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” BitLanders. N.p., 30 May 2014. Web. 15 Jan. 2017.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Dir. Robert Wiene. Babelsberg Studio, 1920. Film.

Thier, Dave. “Shooting the Proscenium Arch: How People Fail to Realize Technology’s Potential.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 16 Mar. 2012. Web. 15 Jan. 2017.

[1] Mise en scène encompasses nearly everything on the screen such as “actors, lighting, décor, props, costume…” (Moura)