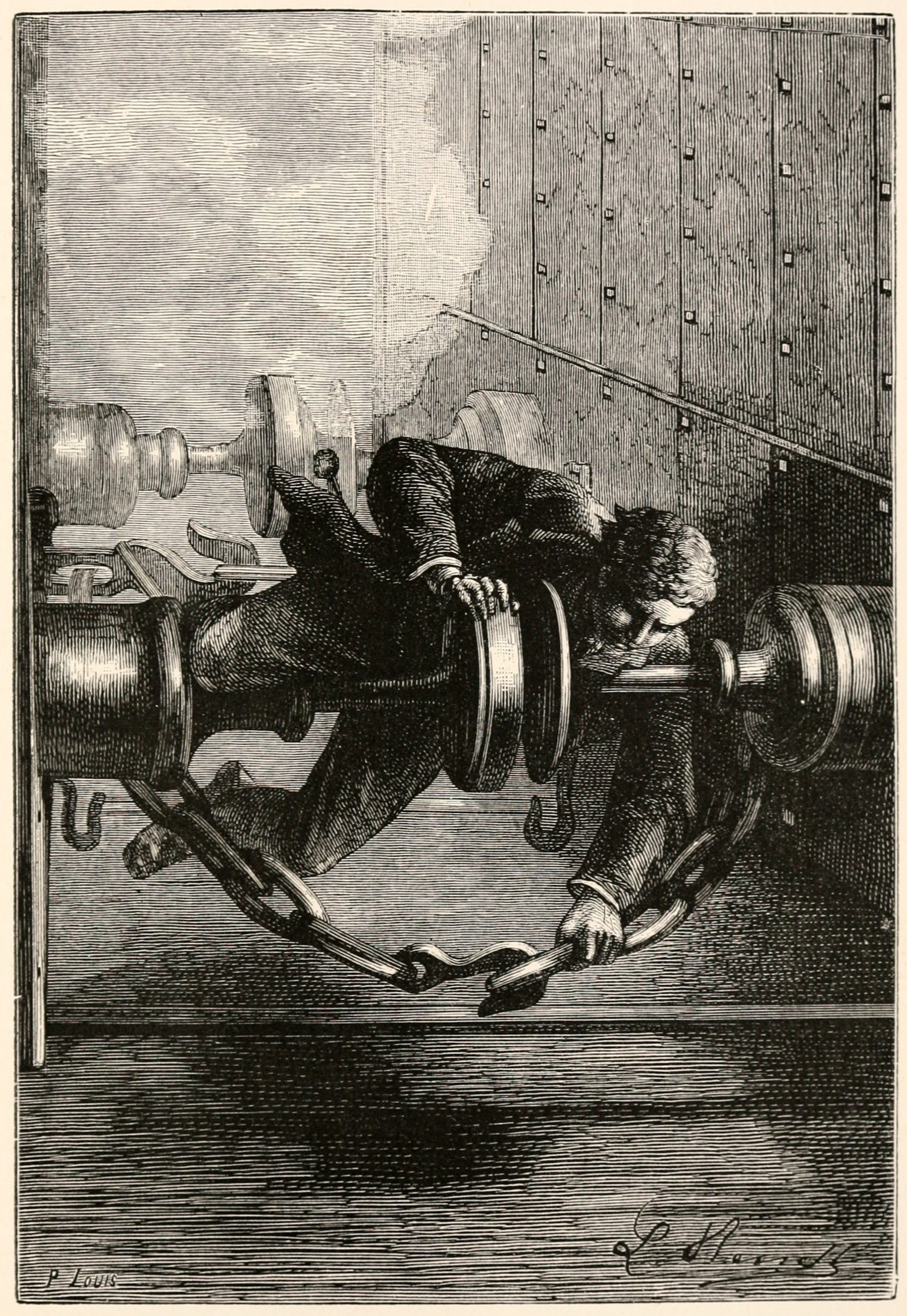

Image from the 1873 edition of Around the World in Eighty Days, illustrator unknown, via Wikimedia Commons.

by Gabriel Bell

Separated by centuries, genres, and even intended audiences, Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando appear to be radically dissimilar texts, and nowhere does that difference reveal itself more obviously than in their handling of time. Observing the sheer importance Verne imbues every passing second with in contrast to the chronological indifference of Woolf’s century-jaunting protagonist, time seems to be a topic where the texts are not simply dissimilar, but are diametrically opposed. One conceives of time as an impersonal unit of measurement that humanity must fit or fall short of, the other as an imprecise experience which is beholden chiefly to a person’s perception of its passing. I argue, in contrast, that a closer reading of either text suggests that both Verne and Woolf engage in criticism of blind adherence to standard time – the former by showing the shortcomings of such blind adherence, and the latter by showing how a defiance of that standard produces a narrative more natural – and arguably more honest – to an individual’s lived experience. What accounts for their diverging deliveries of such a similar criticism, is the historical context of both authors.

Published in 1871, Verne’s Eighty Days is rooted in a time of both radical technological development on the transportation front, as well as one of the most dramatic reductions, both literal and psychological, of distance and travel time in modern history. In view of the effects these reductions had on those in industrial society, Verne endeavors by way of his protagonist to show a man who is an avatar of such society, and to portray his actions as the consequence of dogmatic adherence to this new order. Conversely, Woolf’s Orlando, published in 1928, finds itself steeped in an era of disillusionment that a contemporary of Woolf’s, René Guénon, called the “crisis of the modern world,” as the once-revered innovations of Verne’s day were weaponized against man so destructively in the First World War that industrial society spiraled into disillusionment with the sciences they had so readily entrusted their future to only decades earlier. In this context, Orlando’s disregard for standardized time comes to embody a broader shift in the shape of social and cultural thought across the industrial world: individuals, having their hopes of a grand future through the science of “today” thoroughly dashed, rejected scientific systems and sought to understand the world through a more self-referential lens.

The stance that both texts are substantively an argument against standardized time is not new, and I will rarely contradict existing scholarship on the topic as I find my argument in relative harmony with much of it. However, what existing secondary literature on this topic is markedly hesitant to draw on are the ways in which either text’s historical contexts motivated and shaped a given text’s means of expressing that criticism. Jane Carroll’s “‘You Are Too Slow’: Time in Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days,” for example, makes reference to the most profound technological developments of Verne’s day, but stops just shy of exploring what the attitude of the newly-industrial public was in response to this technology, and how that attitude influenced the tone and technicalities of Verne’s novel. Carroll does assert that Verne’s text embodies the Victorian anxiety that “all of the technology and mechanical progress of the nineteenth century may still end in regression,”[1] but this hinges on the idea that Victorian society saw regression as counterfactual to their own world, implicitly one built on progress and cultivation – a world which Carroll’s paper makes little direct reference to. Discussions of Woolf’s Orlando suffer a similar aversion to historical context. James O’Sullivan’s “Time and Technology in Orlando” makes reference to modernist styles of authorship, but only in the context of Orlando herself adopting them later in the text; it speaks to history only as a literary device within the text, and not in terms of the broader context within which the text was written. This gap in the academic conversation makes for a promising opportunity to contrast the delivery of their similarly-grounded criticisms, as these differences of delivery, I argue, prove to be a telling clue toward the importance of historical context to their creation and consumption. Eighty Days’ juxtaposition of its mechanized air alongside images of travel technologies faltering and failing, as well as Orlando’s unquestioning expression of abnormally-lengthened hours, days, years, and lifetimes, are as much the product of shifting historical thought currents as they are creative choices by their authors, and must be understood as such.

Applying this lens to Eighty Days, it is important to first understand the time, and thus the context, in which Verne writes. Carroll’s work is correct in its assertion that Verne’s text “could only have possibly been written at that time, scarcely four years after the opening of the Suez Canal in November 1869 and three years after the completion of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway.”[2] The practical effect of these developments, historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch writes, was that “any given distance was covered in one-third of the customary time: temporally, that distance shrank to one-third of its former length.”[3] An essential dimension of Schivelbusch’s argument is the equal shrinkage of time and space – as one was reduced, the other necessarily followed, and both would continue to shrink in lockstep with one another throughout the late-nineteenth century. Much more important, however, were the cultural effects of such a shrinkage – what Schivelbusch, quoting an 1893 Quarterly Review publication, casts as the “‘gradual annihilation, approaching almost to the final extinction, of that space and of those distances which have hitherto been supposed unalterably to separate the various nations of the globe… ‘”[4] The effect of this “annihilation” on the industrial world cannot be overstated; the world shrank more significantly during Verne’s day than at any time in living memory, and all at once industrial society came to place itself in the hands of a new time and a new space, profoundly reduced relative to the time and space of its forefathers. Given this context, one may best understand Verne’s argument across Eighty Days not as a total admonishment of modern technology, but as a warning against surrendering fully to standardized time as a self-totalizing law of the universe.

How do the late-nineteenth century’s evolving views on space relate to Verne’s criticisms of empirical time? The answer is found not outside of space, but through it: borrowing an observation from Carroll, Eighty Days may rightly be said to operate under a “chronotope” where in time, space, and money are so inextricably linked that any violation of or impediment on one must necessarily affect the others. Examples abound throughout Eighty Days: governments offer “£25 bonus[es]… every time a ship arrives twenty-four hours ahead of schedule,”[5] and Fogg himself offers the captain of the Tankadère “£100 a day and a bonus of £200 if you get me [to Yokohama] on time.”[6] Even the bet itself is built on these three cornerstones: a wager of £20,000 (money) that Fogg can circumnavigate the globe (space) in eighty days (time). As this relationship is so solid, it stands to reason that an attack on one is an attack on all – that is, that affronts to either space and money may reasonably be called indirect assaults on time as well. Moments like the Indian railway suddenly ending near Kholby, the missing of the train in Nebraska, and the battering of the Henrietta by hurricane-force winds constitute such affronts to both space and money, as they both impede Fogg and company’s capacity to cover ground and, by way of fees for usage and bonuses for timeliness, cost Fogg handsomely. An interesting dimension to these impediments, however, is that their solutions are either low-tech or plainly natural. In India, Fogg and his cohort travel by elephant where the railway cannot take them, and in Nebraska a “sled rigged as a sloop”[7] carries the crew by wind to their final destination.

Of special importance here, however, is the shredding of the Henrietta to make up for its fuel shortage. A steamship, a modern marvel of travel technology, is torn apart and lit on fire to fuel the last of Fogg’s journey – a striking image of the industrial future being consumed by an ancient and undomesticated element, but consuming itself at man’s behest. The burning of the Henrietta also constitutes a divergence between my argument and Carroll’s, as her article goes on to conclude that Eighty Days “may be read almost as an allegory by which Verne suggests that success in business, travel and love, comes only when time is not viewed as rigid or restrictive and when contemporary advances in technology and in society are fully embraced.”[8] On the former moral we agree, but my analysis of Eighty Days argues that moments like the shredding of the Henrietta, among many, many others, come to constitute the heart of Verne’s criticism of empirical time, which is only a part of a wider criticism of blind faith in modernity: that however exceptional these technologies are in their capacity to shrink the world around them, they are nonetheless fallible. In the end, Fogg’s journey, prompted by the uniquely late-nineteenth century sentiment that the world has all but literally shrunk thanks to modern technology, turns out to be saved time and time again by markedly natural, non-industrial methods.

With regard to Orlando’s criticism of standardized time, one must look beyond the immediate world surrounding Virginia Woolf and cast an eye toward the developments to come. Writing in 1928, Woolf lived in a world struggling to reconcile its earlier praise for industrial development with the unprecedented and distinctly mechanized carnage of the First World War. Shattering the view of history as the inevitable march of progress toward the advent of the just society, the First World War called into question what the purpose of this “advancement” was if it were only to result in larger and deadlier conflicts – concerns which were amplified dramatically by the Second World War only decades later. In the wake of that second conflict, writers like Michel Foucault would come to lay the foundation of what is today called postmodernism. Summarizing Foucault’s philosophy, American philosopher Steven Best emphasizes that his work “‘problematizes’ modern forms of knowledge, rationality, social institutions, and subjectivity that seem given and natural but in fact are contingent constructs of power and domination,” and makes particular note of his work on human identity and its relation to power. Best writes:

Human experiences, such as madness or sexuality, become the object of intense scrutiny, discursively reconstituted within rationalist and scientific frames of reference (the discourses of modern knowledge) and thereby made accessible for administration and control. Since the eighteenth century, there has been a “discursive explosion,” according to Foucault, whereby all human behavior has come under the “imperialism” of discursive intervention, regimes of “power/knowledge,” and technologies of truth. The task of the Enlightenment, Foucault argues, was to multiply “reason’s political power” and to disseminate it throughout the social field, eventually saturating the spaces of everyday life.[9]

This perspective on heretofore-accepted “truths” as instead being the imposition of higher institutions or manners of thought, then, begets rebellion of one particular kind – the amplification of the personal over the empirical. Foucault’s (and the broader postmodern tradition’s) emphasis on questioning presumed universal truths and on elevating personal experience over institutionally-imposed categories finds ample representation throughout Orlando, which may have been published well before the advent of a codified postmodern philosophy, but which saw many of the historical and social trends involved in its founding already in motion, albeit nascently. It is through the context of Orlando as a precursor to the emerging postmodernist school that Woolf’s criticism of standardized time may best be understood – that is, as a powerful endorsement of the emerging school of personalized time.

Orlando rarely delivers its endorsement of personalized time via direct address, often preferring to let its disregard for and bending of that standard speak for itself, but it finds a rare direct mention in its second chapter. Here, the novel’s narrator expounds on how “an hour may be stretched to fifty or a hundred times its clock length” in one person’s subjective experience, and that this “extraordinary discrepancy between time on the clock and time in the mind is less known than it should be and deserves fuller investigation.”[10] Unique within Orlando, this passage is a rare active call for personal interpretations of time to be placed at the forefront of discourse on lived experience, but it also has the more subliminal effect of conflating “time on the clock” and “time on the mind” in its argument – here, they are two items on the same list, described with much the same language, devoid of the usual subjugation of the psychological to the chronological. In a similar vein, O’Sullivan’s work rightly argues that Orlando “demonstrates that subjective time holds personal prominence over any objective measure”[11] and concludes that it “is not until Orlando makes herself a product of her own time—achieved with the aid of her external devices—that she becomes an embodied self.”[12] Of special importance here is the use of the phrase “her own time,” not describing her as coming to possess one century or generation as her own – after all, she lives across several – but characterizing her rejection of any given century or generation in favor of a time wholly her own and wholly weighted according to the subjective power of each moment.

The reality of Orlando’s living across centuries also comes to constitute the text’s main way of advocating for personalized time, where its flagrant disregard for universally-understood standards implicitly undermines the power of those metrics on Orlando’s own perception. Look to the text’s loose-fitting application of chronological benchmarks in its overall narrative: centuries come and go under the reader’s nose, and the few times the date is mentioned, the leap from the last stated time is titanic. O’Sullivan’s work identifies this as Orlando “problematiz[ing] conventional periodization,” looking to the portrayal of the nineteenth-century’s dawn and remarking that “[f]emale oppression did not immediately evaporate with the close of the Victorian age, and to make cultural distinctions in such a chronological fashion is, to Woolf, an arbitrary endeavor.”[13] In a similar vein is the leap from chapter three, which begins with the reign of Charles I, to chapter four, which ends a mere fifty-eight pages later with the dawn of the nineteenth century. Some one hundred and fifty years have passed between the two chapters, yet Orlando remains alive and much the same person and age. Either case demonstrates how this disregard for symbols of standardized time, in this case centuries or “ages,” is not mindless, but intentional in its message – the real measure of Orlando’s life rarely aligns with the measure of the world around them, but this in no way devalues or diminishes their lived experience. That latter leap of one hundred and fifty years also constitutes a step up from the earlier claims made by chapter two – far from merely saying internal time should be taken into account, the narrative externalizes its character’s own perceptions of time, mapping them onto the “real” world. In so doing, Orlando’s narrative treats these jaunts across time as unquestioningly as one would treat a standard human lifetime, and that refusal to question such a preternaturally long life and document these great chronological leaps without implying they are unnatural or incongruous with reality is itself another subliminal endorsement of personalized time, coming not by way of what the text outright says but what it makes a point to not say. This narrative-wide diminution of standardized time is the heart of the text’s criticism, as it is a practical – albeit fictionalized – application of exactly what the text encourages the reader to do: to put the markers and milestones of standardized time by the wayside and consider the personal weight of each passing moment. In its proper historical context, one can come to see this call to action as an embryonic form of a more self-referential worldview which did not fully emerge in Woolf’s lifetime, but saw its motivating cultural and philosophical shifts begin to emerge into formal development around the era of Orlando’s publication.

Ultimately, the conclusions drawn by scholars like Carroll or O’Sullivan are in large part honest to both the broader themes and finer details of their respective texts, and are truthfully only one dimension shy of a sufficiently complete understanding of either. What I argue is that this neglected dimension, the influence of history, is non-negotiable, and neither text can ever hope to be fully understood without proper reference to history’s influence over the worlds, lived experiences, and personal philosophies of either author.. It is true that Verne’s text concludes on the notion “that success in business, travel and love, comes only when time is not viewed as rigid or restrictive…”[14], just as it is true that Woolf’s text “demonstrates that subjective time holds personal prominence over any objective measure”[15] but these ideas are not without origin. By placing both texts in their respective historical contexts and viewing them as being equally products of their authors and their eras, a fuller, more extensive understanding of both texts emerges. One comes to conclude that both texts make a substantially similar argument – that standardized time has its shortcomings, and must not be blindly submitted to out of fear of losing some part of one’s life or self – but different perspectives of what exactly is lost and why exactly one ought not trust standardized time emerge based on historical context. Verne, writing in a world utterly enthralled with modern marvels of transportation like the railway and the steamship, cautions against standardized time just as he cautions against blind adherence to many of the technologies of his day – on the grounds that they are not perfect, and to buy into them as though they were is to put oneself, uninformed and unquestioningly, at the mercy of uncertain and unstable machinery. Woolf, living at the end of that illusion of progress and the beginning of a period of questioning and reflection, openly advocates for personal time as an alternative to standardized time, believing that submission to the latter sacrifices the depth of the personal experience, and that only the former can maintain the self in the fullest sense. Although they are dissimilar works in their finer details, it is through their shared warning against a strict and dogmatic adherence to universal standards of chronology that these two texts find common ground, and by understanding their respective criticisms as products of their historical contexts, one finds them to be two voices in the same choir.

Endnotes

[1] Jane Suzanne Carroll, “‘You Are Too Slow’: Time in Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days,” in Victorian Time: Technologies, Standardizations, Catastrophes, ed. Trish Ferguson (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 81.

[2] Ibid, 78.

[3] Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (Oakland: University of California Press, 1977), chap. 3.

[4] John Murray, The Quarterly Review (London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1839) quoted in Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey, chap. 3.

[5] Jules Verne and William Butcher, Around the World in Eighty Days (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 29.

[6] Ibid, 105

[7] Ibid, 172

[8] Carroll, “‘You Are Too Slow’,” 92.

[9] Steven Best, “Foucault, Postmodernism, and Social Theory,” in Postmodernism and Social Inquiry (London: UCL Press, 1994), 28-29.

[10] Virginia Woolf, Orlando (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 59.

[11] James O’Sullivan, “Time and Technology in Orlando,” in ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Stories, Notes, and Articles 27, no.1 (Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis Inc., 2014), para. 7.

[12] Ibid, para. 11.

[13] Ibid, para. 6.

[14] Carroll, “‘You Are Too Slow’,” 92.

[15] O’Sullivan, “Time and Technology,” para. 7.

Works Cited

Best, Steven. “Foucault, Postmodernism, and Social Theory.” Postmodernism and Social Inquiry, 1995.

Carroll, Jane. ““You Are Too Slow”: Time in Jules Verne’s around the World in 80 Days”.” Victorian TIme: Technologies, Standardizations, Catastrophes, 2013, pp. 77–94.

O’Sullivan, James. “Time and Technology InOrlando.” ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, vol. 27, no. 1, 2 Jan. 2014, pp. 40–45, https://doi.org/10.1080/0895769x.2014.880143.

Verne, Jules, and William Butcher. Around the World in Eighty Days. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 11 Sept. 2008.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch. The Railway Journey : The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century. Berkeley ; Los Angeles, The University Of California Press, 1986.

Woolf, Virginia. Orlando. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015.