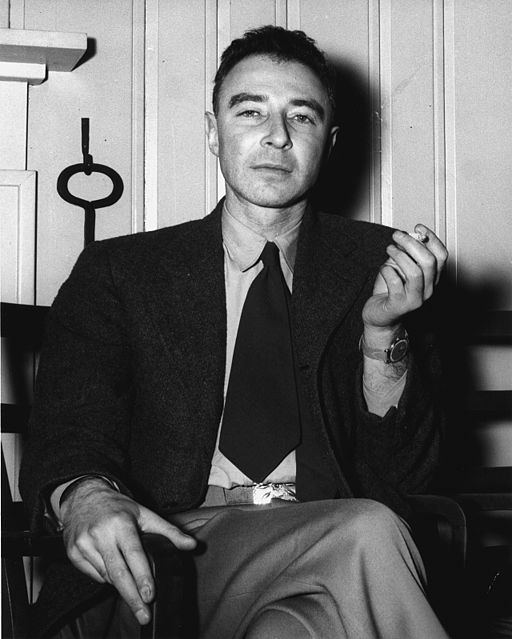

J. Robert Oppenheimer in 1946, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

by Jastej Luddu

Heinar Kipphardt’s In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer recounts the trial of one of the most prominent physicists in history. Oppenheimer, often called the father of the atomic bomb, was summoned before the Atomic Energy Commission in 1954 and interrogated on his loyalty to the United States. His opposition to the hydrogen bomb and past left-wing leanings made him the target of Communist suspicions. Kipphardt’s play features many speeches and monologues concerning the accusations levied against Oppenheimer. These speeches also deal with larger thematic issues such as ideology, violence, and the purpose of science. The opening and closing speeches of the play, both spoken by Oppenheimer, illustrate the complex forces and motivations that influenced the physicist. They embody the intellectual struggle he faced, his allegiance torn between his nation and his conscience.

The play begins with a projection of several images onto white hangings that “separate the stage from the auditorium” (Kipphardt, 9), before opening and revealing the stage itself.

Scientists in battledress, looking like military personnel, are doing the countdown, for test explosions – 4-3-2-1-0 (in English, Russian, and French). (Kipphardt, 9)

Although this line of stage direction is not part of a speech, it provides important background to the proceedings set to commence. It describes scientists “looking like military personnel”, counting down, in several languages, before “atomic explosions” light the sky. Kipphardt is referencing events without which there would be no trial: the birth of the atom bomb and its devastating aftermath. But the projections lend more than historical context to the play; they also establish perspective. The direction “scientists in battledress” addresses the tension between the physicist’s discipline and his government. Is he devoted to his field, the realm of scientific progress, or does he yield to his patriotism, his obedience to his nation? Anyone observing scientists in military garb might conclude the latter is the more likely scenario. By aiding in the creation of such terrible power, the physicist cemented his partnership with the government. Arguments are made from both positions throughout the play. The Atomic Energy Commission is trying to determine whether Oppenheimer can keep his security clearance. Oppenheimer is cross-examined in the play, his personal views and convictions are scrutinized. However, perspective is critical. The first few lines of the play can be deconstructed in many ways. They can be seen as confirmation of the government appropriation of science, or simply as a depiction of physicists making an important discovery. Regardless of which interpretation one favours, what is most significant is that this image is broadcast to the audience before the play begins. It reminds those viewing the production of the weight behind every single word uttered on stage.

Oppenheimer’s first speech, which opens the play, follows a sketch of the room in which the hearings are being held, as well as a description of Oppenheimer himself:

Robert Oppenheimer enters Room 2022 by a side door on the right. He is accompanied by his two lawyers. An official leads him diagonally across the room the leather sofa. His lawyers spread out their materials. He puts down his smoking paraphernalia and steps forward to the footlights. (Kipphardt, 9-10)

While seemingly innocuous, there is careful detail in this paragraph. Oppenheimer “steps into the footlights” before making his statements, in a grand manner. He is not set to make remarks to himself, but at the same time his words will not address others in the room. Like the projections, his speech will speak to the audience, the public, through the voice of the actor playing him:

Oppenheimer. On the twelfth of April 1954, a few minutes to ten, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Professor of Physics at Princeton, formerly Director of the Atomic Weapons laboratories at Los Alamos, and later, Adviser to the Government on atomic matters, entered Room 2022 in Building T3 of the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington to answer questions put to him by a Personnel Board, concerning his views, his associations, his actions, suspected of disloyalty. (Kipphardt, 10)

The question of perspective is especially evident in this speech. Who is speaking? In his introduction to the play, Kipphardt concedes that In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is “not an assemblage of documentary material” (Kipphardt, 5). Every testimony is stitched together from “three thousand typewritten pages” published by the Atomic Energy Commission in regards to the Oppenheimer hearings (Kipphardt, 5). Not every word attributed to a character in the play was said by the same person in the actual trial. The longer monologues were introduced by Kipphardt himself, and didn’t actually take place. Kipphardt “tried to evolve these monologues from the attitudes adopted by these persons”, attempting to stay true to the feelings felt by those involved (Kipphardt, 6). Hence the Oppenheimer put on trial in the play is not the same Oppenheimer investigated in real life.

Oppenheimer does and does not present the first speech. In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer showcases Oppenheimer the character, not the person. This character, although possessing an assortment of the real Oppenheimer’s qualities, isn’t an entirely factual representation. Add to the mix that an actor portrays this Oppenheimer facsimile and one notices the layers Kipphardt is working with. Oppenheimer’s opening speech is critical to the play because it literally sets the stage. The actor steps outside the play and communicates “facts” to the audience. The actor hasn’t assumed the role of Oppenheimer yet. He takes a moment to provide context, not as Oppenheimer, but as someone playing Oppenheimer. The actor robotically delivers details about the case, along with some basic occupational and biographical information about Oppenheimer. This is done to remind the audience they are indeed watching a play, and not historical footage. None of the other characters on stage respond to Oppenheimer’s monologue. Oppenheimer introduces a projection of Joseph McCarthy, the US senator who presided over the Communist witch hunts. After the projection ends, members of the Personnel Security Board enter, and nonchalantly McCarthy is brought up. They’re not mentioning McCarthy in light of Oppenheimer’s words, but the timing is important. It shows that the supposed threat of Communism is on everyone’s minds, and also demonstrates that Oppenheimer’s speech was only heard by one group: the audience. Oppenheimer himself didn’t hear his words, as he wasn’t speaking them; the actor playing him was. The initial appearance of McCarthy in the play is done for the benefit of the audience, for the purpose of context. The play doesn’t become a play until the Personnel Security Board appears on the stage. Before they enter, there is just a stage and a few men shuffling in preparation: in preparation for the hearing, one would assume, but also in preparation for the play. Kipphardt briefly creates a rift between art and life at the beginning of In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, and although it passes unnoticed, it asks questions about the nature of perspective. As the audience sits still, unmoving in their seats, they are exposed to quite subtle shifts in scene, appearance, and reality.

While spoken by Oppenheimer as well, the monologue that ends the play is very different from the one that starts it off. In many respects, the final speech is a sort of anti-soliloquy, delivered by someone who, though not alone, might as well be. Oppenheimer has already been found “guilty” and his security clearance is to be revoked. Two members of the Personnel Security Board have already spoken, and have now given the floor to Oppenheimer. What follows is a speech delivered by an Oppenheimer sounding nothing like the Oppenheimer that opened the play.

Oppenheimer. When more than a month ago, I sat for the first time on this old sofa, I felt I wanted to defend myself, for I was not aware of any guilt, and I regarded myself as the victim of a regrettable political conjunction. But when I was being forced into that disagreeable recapitulation of my life, my motives, my inner conflicts, and even the absence of certain conflicts – my attitude began to change… As I was thinking about myself, a physicist of our times, I began to ask myself whether there had not in fact been something like ideological treason… (Kipphardt, 126)

By the conclusion of the play, the actor is immersed in is role. He has been speaking as Oppenheimer for almost the entirety of the production. He has recounted memories, stated opinions and presented the ideological battles Oppenheimer faced. This speech mirrors a classical soliloquy in the heaviness of its subject matter; Oppenheimer is baring his soul. Early on, he makes a very striking statement, conceding his guilt. But it is not the same guilt the Personnel Security Board was searching for. The chief counsel for the Atomic Energy Commission, Roger Robb, alluded to Oppenheimer as “the traitor for ideological, ethical… motives” that appeared “in the most vital sphere of nuclear energy” (Kipphardt, 21). He’s referring to Oppenheimer’s hesitance towards endorsing the hydrogen bomb. But Oppenheimer continues to speak about the physicist’s treachery not to his government, but to science.

Oppenheimer recognizes the relationship science has entered into with the state, and what impact that has had not only on the products of scientific progress, but on science’s reputation.

Even basic research in the field of nuclear physics is top secret nowadays… Our laboratories are financed by the military and are being guarded like war projects. When I think what might have become of the ideas of Copernicus or Newton under present-day conditions, I begin to wonder whether we were not perhaps traitors to the spirit of science when we handed over the results of our research to the military, without considering the consequences. Now we find ourselves living in a world in which people regard the discoveries of scientists with dread and horror, and go in mortal fear of new discoveries. (Kipphardt, 126)

By supplying the government with knowledge mined from hours of study and experimentation, Oppenheimer and his ilk betrayed “the spirit of science”. They were so intoxicated with the possibility of what they could achieve, they did not ask whether they should[1]. Thus, science became more intertwined with politics and violence. Charles Thorpe’s “Violence and the Scientific Vocation” addresses this issue:

Modern violence itself takes on an increasingly ‘scientific’ character – impersonal, institutionalised, and rationally organized… And science has become integral to the technological sophistication and power of modern warfare. Modern military strategy ranges from what Vannevar Bush called the ‘science’ of total war to more recent developments in ‘smart bombs’ and ‘surgical strikes’. Yet, despite the pervasiveness of the modern integration between science and violence, the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki stand out as iconic, symbolically encapsulating the entire horror of 20th century total war. (Thorpe, 60)

The institutionalization of violence has progressed along with science. Curiously, the more methodic the process of violence becomes, the more violent it is. The creation of the atomic bomb was the most systematic and structured operation ever undertaken by scientists and the state. It also resulted in the most destructive weapon ever used in human history. Oppenheimer wishes the “utopian idea” of atomic energy, “produced equally easily and equally cheaply”, had been realized instead of the alternative (Kipphardt, 26). But one might ask whether such an idealistic notion could have been realized with the state involved. Perhaps government intervention in scientific matters benefits nobody but those who can take advantage of the most deadly outcomes of technological progress.

In any case, Oppenheimer reaches an epiphany of sorts by the end of his monologue:

… I ask myself whether we, the physicists, have not sometimes given too great, too indiscriminate loyalty to our governments against our better judgement – in my case, not only in the matter of the hydrogen bomb. We have spent years of our lives in developing ever sweeter means of destruction, we have been doing the work of the military, and I feel it in my very bones that this was wrong… I will never work on war projects again. We have been doing the work of the Devil, and now we must return to our real tasks… We cannot do better than keep the world open in the few places which can still be kept open. (Kipphardt, 127)

“The work of the military” is equated with “the work of the Devil”, summing up Oppenheimer’s journey from physicist to government scientist and then back again. His association with the state and military work reveals to him the worth of scientific exploration. Progress and knowledge can be utilized in many ways, and Oppenheimer recognizes the scientist’s responsibility. He cannot stumble upon a discovery, throw up his arms, and surrender it to the powers that be. He has to take into account how his discovery may be used, for better or for worse. Oppenheimer vows to never work again on a war project, instead aiming to focus on research and keeping the world open where it can be. The play ends on this emphatic note, and it stands as a testament to the overcoming, however small or late, of the human spirit over the all-powerful forces of government and bureaucracy.

The main perspective of In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is effectively deconstructed through the speeches that open and close the play. Kipphardt places at the beginning an Oppenheimer trying to feel comfortable in his skin, an actor filling out the edges. The monologue shifts through several perspectives, providing illuminating context for the audience/reader while making a statement about the nature of Oppenheimer’s condition. The play’s final speech employs an experienced Oppenheimer ready to tackle the tough issues. Important ideas concerning the role of the scientist are dissected by Oppenheimer in his anti-soliloquy, resulting in a rejection of the paradigms put forth by the state. Kipphardt takes the “matter” of J. Robert Oppenheimer, his environment, his opinions, his jobs, his relationships, his field, and zeroes in on his smallest and most basic trait: his character. Kipphardt then splits this atom in two. Examining one half of this atom is not enough; both sides deserve inspection, along with the explosive story they tell of a man divided between the countless beliefs raging within him and his environment.

References:

Kipphardt, Heinar. (1967). In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Hill & Wang.

Thorpe, Charles. (2004). “Violence and the scientific vocation.” Theory, culture & society 21.3: 59-84.

[1] In order to meet the minimum requirement for pop culture references per essay, I’d like to point out that a similar line is spoken by Jeff Goldblum’s character Ian Malcolm in Jurassic Park: “…your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.”