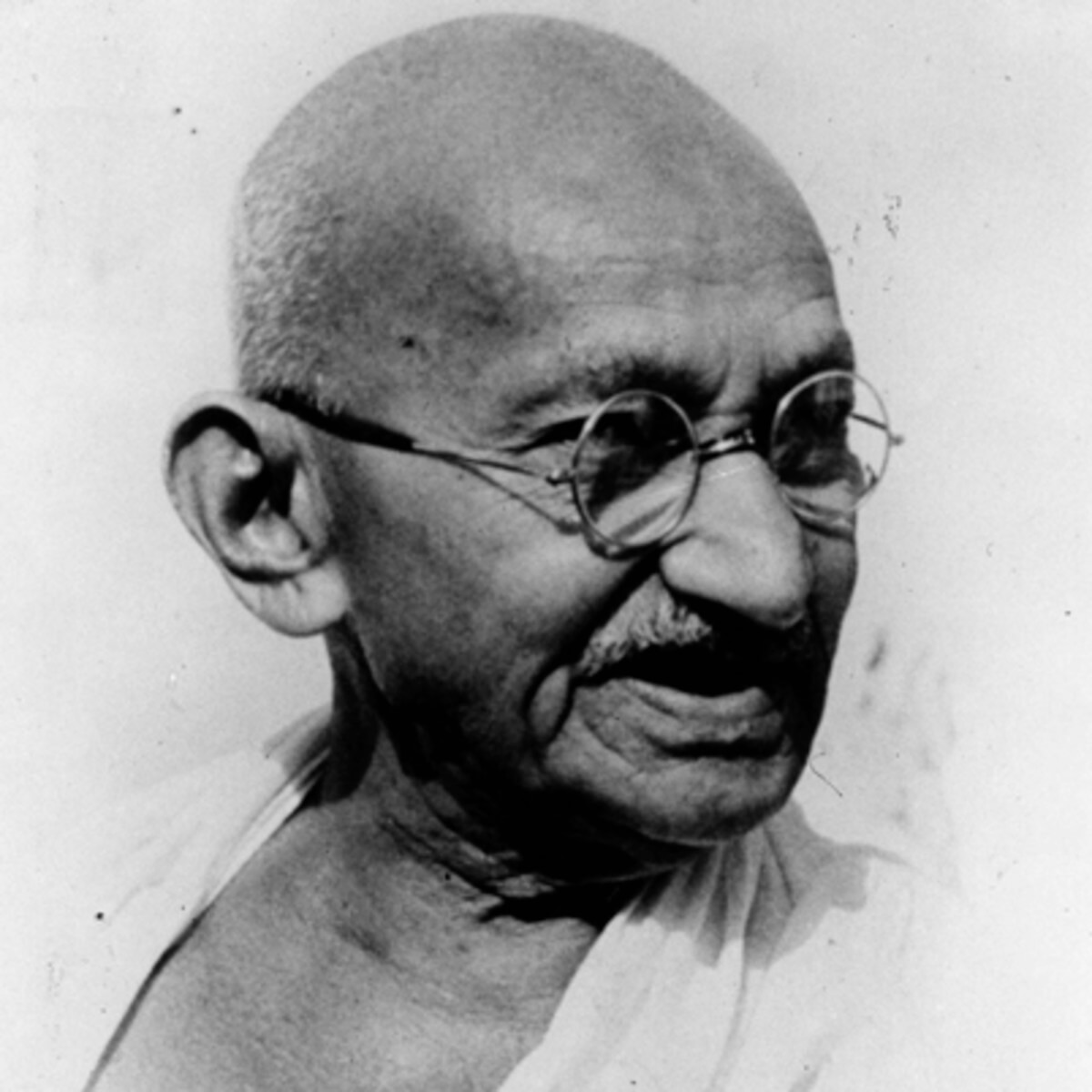

Photographer unknown. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

by Annabel Smith

Mohandas K. Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj is an essential text of the Indian liberation and postcolonialism movements, providing a scathing critique of modernity and its impacts on the relationship of the individual to the world around them. In his text, Gandhi discusses at length the development of English colonialism in India, and the factors that contributed to its continued dominance. He characterizes the two nations as fundamentally different, portraying a moral, spiritual Indian civilization and an immoral, secular England. This difference stems from the emphasis that Indians collectively place on morality that is absent from the English nation. Gandhi argues not only that this leaves the English more susceptible to the evils of modernization, but also that the ways in which modern technology and institutions restructure people’s relationship to the world around them pose a threat to Indian civilization. Modern technology, in his view, breeds immorality by erasing the good work involved in the achievement of one’s goals, perpetuating the idea that the ends justify the means. It poses a threat to the future of civilization by leading the people subject to it to view further development as the only way forward. To Gandhi, it is the development of modern civilization itself that is the driving force behind the origins and continuation of colonial rule.

Gandhi’s relationship with modernity is a complicated and at times contradictory one. His writings present a rejection of technology that was not always reflected in his real-life use of modern inventions such as railways and medicine, arguing that these technologies breed immorality while using them himself. Various critics have differing perspectives on Gandhi’s view of modernization, depending on their reading of Hind Swaraj as a set of teachings that should be taken either literally or metaphorically. For Esha Shah, Hind Swaraj represents an ideologically pure “Gandhism,” with his sweeping anti-technology fundamentalism indicating an impossible ideal that must still be pursued. Shah’s critique focuses largely on the ways that these implements of modernity shift one’s way of thinking, causing people to become more immoral and accept constant development as the only possible future. Douglas Allen presents an alternative view in his work, reading Hind Swaraj much more metaphorically than Shah. He sees the text as largely abstract and decontextualized, critiquing what modernity represents rather than what it actually is. Theresa Lee, in her comparison of the philosophies of Gandhi and Sun Yat-sen, views the common interpretations of Gandhian philosophy in the modern day as problematic and dangerous. She identifies a tendency to erase his goals of realizing a true postcolonial society and his rejection of the English idea of modernity in favor of a watered-down, pacifist form of Gandhism. My analysis seeks to prove that Gandhi’s critique of modernity should be understood on both literal and figurative levels. He argues that technology is responsible for breeding immorality, while recognizing that a complete rejection of modernity is impossible when one exists as an active member of society.

To Gandhi, Indian and English civilization are fundamentally different because Indian civilization is built on a foundation of shared moral values, while the English are united as a political but not spiritual whole. This creates a dichotomy between the moral and the material civilization, where the oppressor nation strives for material gains and the subjugated nation seeks a higher, moral advancement. For Gandhi, spirituality and morality are deeply connected, with spirituality presenting a superior alternative to the materialism of modernity. Gandhi describes civilization as “that mode of conduct which points out to man the path of duty…If this definition be correct, then India, as so many writers have shown, has nothing to be learned from anybody else” (Gandhi, 67). In Gandhi’s view, Indian civilization is built on the pillars of self-knowledge and morality, which is how India manages to remain “sound at the foundation” (66) even as it has moved from the ancient to the modern world. Religion is also central to the nationalist argument, with nationalists using India’s rich history of spirituality in their advocacy for Home Rule. For Gandhi, this spirituality has a different significance, as his goal goes beyond driving the English out of India and amounts to the creation of a new kind of postcolonial society. The issue of secularization exemplifies his fears concerning the erosion of these Indian moral values, as he writes, “Religion is dear to me, and my first complaint is that India is becoming irreligious. Here I am thinking…of that religion which underlies all religions. We are turning away from God” (42). English civilization, conversely, is founded on immorality, as the “path of duty” their civilization directs them to leads the English to seek material, rather than moral, advancement. The English are completely disconnected from this “religion that underlies all religions,” as Gandhi claims that “money is their God” (41). The values of the English civilization, according to Gandhi, are not based on the practice of a moral way of life. The colonial presence of the English in India is motivated by their pervasive materialism, and the influence of materialism has proven to be a disruption to the fundamental morality of civilization in India.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that the idealized, moralistic India that Gandhi describes is one which has never really existed. This version of Indian civilization is not a historical one but Gandhi’s imagining of a future postcolonial India, built upon the country’s sound moral foundations that he has already identified. In Hind Swaraj, independence represents a way forward to a postcolonial future, rather than a way back to the way things were in India before English colonialism. Gandhi is aware of this contradiction, writing, “My patriotism does not teach me that I am to allow people to be crushed under the heel of Indian princes, if only the English retire. If I have the power, I should resist the tyranny of Indian princes just as much as that of the English” (Gandhi, 76). Subjugation under one’s own countrymen is still subjugation, as Gandhi points out here in his critique of past Indian princes. However, Gandhi speaks of India as made up of its people, rather than its institutions or its history. This is very significant to his argument, as he believes the present and future condition of Indian civilization is dependent on the beliefs and actions of its people rather than the moral values, or lack thereof, of its ruling powers. Of Gandhi’s postcolonial aims, Lee writes, “Independence is simply a precondition to building the kind of postcolonial society that Gandhi had envisioned for India, and arguably beyond” (Lee, 146). His goal is not limited to the expulsion of the English from India because a return to an oppressive power structure is antithetical to the message of swaraj, or self-rule. The concept of swaraj, as Gandhi defines it, does not simply refer to rule by one’s own countrymen rather than rule by outsiders. Self-rule in India can only be achieved when society is structured based on the moral values of Indian civilization. Gandhi’s ideal society is just as impossible under India’s pre-colonial regimes as it is under English rule.

The moral principles that Gandhi sees as foundational to the Indian national identity are corrupted by the modernizing influence of the English. Gandhi views technology as a largely evil force that hinders us from the pursuit of self-knowledge that is so essential to swaraj. The ease with which modern technology allows people to perform various tasks is generally thought of as a positive feature of modernity, but Gandhi is more skeptical. In his view, hard work is integral to a moral way of life: “Nature has not provided any way whereby we may reach a desired goal all of a sudden. If, instead of welcoming machinery as a boon, we would look upon it as an evil, it would ultimately go” (Gandhi, 111). He extols the merits of hard work in the achievement of one’s goals, and the idea that technology can be used to erase this work is repugnant to his ideas of self-improvement and self-rule. A prominent example of this in Hind Swaraj is Gandhi’s critique of the railways:

Good travels at a snail’s pace – it can, therefore, have little to do with the railways. Those who want to do good are not selfish, they are not in a hurry, they know that to impregnate people with good requires a long time. But evil has wings. To build a house takes time. Its destruction takes none. (47)

To Gandhi, it is the speed and convenience of railways that makes them immoral. They spread evil more easily by transporting evil people at a greater speed. More significantly, however, we lose our penchant to do good when we travel on the railways, as we become accustomed to having the work of our lives done for us. This speaks to the European “[addiction] to the limitlessness of the future” (Lee, 149), as the European idea of modernization hinges on constant developments in technology that improve the ease of our lifestyle. However, Gandhi claims that we lose our virtues of discipline and self-knowledge in this quest of progress for the sake of progress.

Gandhi’s critiques of technology here present an ideological purity that even he himself could not live up to in his day-to-day life. Hind Swaraj condemns these technological developments across the board, even those that Gandhi himself was guilty of using (Allen, 111). Shah interprets Gandhi’s strict anti-technology views as an element of confusion in his relationship with modernity: “Gandhi does not oppose technology per se but its non-technological core and what it does to human experience or consciousness; he talks about what it means to be a human being shaped by such a technological mode of thinking” (Shah, 126). His critique of modernity is complex, per Shah, because it is not the developments in and of themselves that are immoral, but the ways in which we come to interact with the world because of those developments. In Shah’s view, the contradictions in the text are intentional, meant to demonstrate an aspirational level of moral purity. Critiques of elements of modernity such as medicine, law, or railways are meant to show what happens to a person going through the world in interaction with these institutions and colonial implements, not necessarily as criticism of the technology on its own. Conversely, Allen identifies this as indicative of Gandhi’s hypocrisy:

He may dogmatically dismiss modern hospitals and modern medicine as evil, but he goes to the modern hospital when faced with life-threatening appendicitis. He may dogmatically dismiss railways, but no one uses railways more than Gandhi to promote his values and energize the masses. (Allen, 111)

Allen views the actions advocated by the Editor as a hypocritical flaw in Gandhism, since Gandhi is guilty of taking advantage of the very technologies that he condemns. However, it seems that the large-scale condemnations of institutions from which Gandhi benefited that are present in Hind Swaraj are indicative of the realistic swaraj efforts that he describes. In the conclusion to Hind Swaraj, Gandhi presents a list of actions that people in different circumstances can take to promote self-rule (Gandhi 115). This call to action suggests different steps that can be taken by people with various resources or roles in society. In contrast with his total rejection of technology in earlier sections of the text, Gandhi suggests here that this immorality is something that should be held in mind and it is unreasonable to expect even the most morally pure of Indians to act with complete purity. He acknowledges that with different means, one must take different actions.

The crux of Gandhi’s criticism of technology and modernization in India is the ways in which modernity perpetuates the idea that the ends justify the means. For Gandhi, the ends and means are inseparable. This can be seen in his aforementioned condemnation of technology, where the hard work and good intentions involved in performing a task inform its moral purity, a purity that is erased when the ease of achieving something increases. Allen describes the dominant view of modernity in his writing on Gandhi: “As formulated by a wide variety of Western anti-modernists and post-modernists […] and as critiqued by existentialists and phenomenologists, this dominant modern approach embraces the view that the ends justify the means” (Allen 115). This is at the center of Gandhi’s moral opposition to the modern world in general and to modernity as exemplified by the English in particular. For Gandhi, being good comes from living and acting in a way that is good. Morality is not something that can be circumvented. Modern ideals, however, have made prevalent the idea that we can achieve noble aims without doing the necessary work, or through work that he considers to be improper and immoral. He condemns this idea, saying, “I am not likely to obtain the result flowing from the worship of God by laying myself prostrate before Satan. If, therefore, anyone were to say: ‘I want to worship God, it does not matter that I do so by means of Satan’ it would be set down as ignorant folly. We reap exactly as we sow” (Gandhi 81). This imagery comes from an argument regarding the use of brute force in the achievement of Home Rule in India, where he argues that freedom accomplished through the use of violence is not freedom, as the end result of an action is inseparable from the methods used to accomplish it. True peace can only be achieved by peaceful means.

Recognizing modernization as responsible for intensifying English immorality and eroding Indian morality, it follows that Gandhi views modernity itself as responsible for the evils of colonialism. Gandhi identifies a negative cycle in the spread of modern technology and institutions in India, where modern developments lead to a rise in immorality, which in turn causes further development. This occurs when the institutions and technologies that Gandhi classifies as immoral become largely accepted, which he argues is often influenced by the supposed perception of India by Western nations: “There is a charge against us that we are a lazy people, and that the Europeans are industrious and enterprising. We have accepted the charge and we, therefore, wish to change our condition” (42). The evaluation of Indian society by English standards that we see here causes an imbalance in the relationship between moral (Indian) and immoral (English) civilization. When immoral civilization is lauded as good and moral civilization is made to seem unfavorable in comparison, the society that is looked down upon will necessarily desire to advance. In this case, the consequence of this is India becoming more like England. Additionally, Gandhi argues that modernization creates artificial problems that it then claims to solve, writing, “An opium-eater may argue the advantage of opium-eating from the fact that he began to understand the evil of the opium habit after having eaten it” (49). In India, colonial powers have swooped in and created problems, then “solved” those problems with their modern methods. Here, Gandhi is speaking in reference to the supposed issue of divisions among India’s large population that the English, like the opium user who understands the problems with opium after using it, have attempted to solve through the introduction of railways and English law. For Gandhi, this is a way for colonizers to influence the colonized to accept their subjugation as a positive force.

When a society accepts these modern influences as necessary for its advancement, that society is led to believe that that version of modernity is the only future possible. In her critique of Hind Swaraj, Shah describes Gandhi’s condemnation of technology as a negative enframing of consciousness, wherein the problem is not with technology itself but the way it structures our thinking and interactions with the world. Gandhi illustrates this enframing of consciousness in his discussion of the practice of medicine:

I over-eat, I have indigestion, I go to a doctor, he gives me medicine, I am cured, I over-eat again, and I take his pills again. Had I not taken the pills in the first instance, I would have suffered the punishment deserved by me, and I would not have over-eaten again. (63)

Modern medicine is a problem for Gandhi because it reconstructs our relationship with our body and the world around us. Rather than pursuing the self-knowledge that he sees as essential, when we act in error we are encouraged to continue to do so because there is an easy cure, eliminating the work involved. In Shah’s words, “Technology alters our experience of the world and, in doing so, mutates, downplays and even undermines or makes it impossible to experience this world differently. Technology operating like a rationalising force makes any alternative imaginations impossible” (Shah 130). According to Shah, Hind Swaraj teaches that becoming dependent on technology instead of learning from our interactions with our bodies and the world around us makes a way forward without continued technological advancement seem increasingly impossible. A literal interpretation of these teachings, as Shah advocates for, implies that present-day society, over a century after the writing of this text, is effectively doomed, with further technological developments that have led to further disconnects between mind and body. However, as Gandhi describes individual self-rule as a process that anyone can undergo, it is clear that he sees this dependence as something we are able to control to some extent. The process of swaraj is one that frees people from the rule of ideas and developments as well as the rule of human oppressors.

The cognitive restructuring that comes with the conveniences of modernity is proven to exist by Gandhi’s own historical recasting. As a radical advocate of postcolonialism and critic of modernization in life, Gandhi’s posthumous portrayal as a pacifist with widely palatable views demonstrates the cognitive dissonance that comes with modernity. We are not doing the true work of swaraj when we reject colonial rule while accepting its legacy, meaning we must make Gandhian philosophy acceptable to the colonial legacy as well. The embrace of this conception of modernity as the only way forward conflicts with Gandhi’s (questionable) status as something of a modern saint, since the views he expresses in his writings condemn the very things that make this progressive view possible: “By recasting Gandhi as a harmless Luddite with a contemporary moral sensitivity which is fit for progressive global causes, the global community has conveniently tamed an otherwise relentless critic of modernity as setting the definitive standard of life” (Lee, 149). Lee identifies the contradiction here between Gandhi’s portrayal and his actual views and actions as emerging from a sort of widespread cognitive dissonance, wherein the hero-worship of Gandhi as an advocate of peace and nonviolence is impossible when we ascribe fully to the necessity of constant development. Erasing the complexities of Gandhi’s view of modernity in Hind Swaraj allows readers to embrace ideas such as passive resistance while rejecting his criticism of technology . Allen embraces a more nuanced view of Gandhian philosophy, writing, “Yes, Gandhi is opposed to the key terms as defined by modern civilization in the above modern formulation of the either-or dichotomy. However, he is in favor of real progress, real development, appropriate technology, and raising the standard of living of all” (Allen, 122). As Allen points out, Gandhi’s purported desire to eliminate machinery, as seen in Hind Swaraj, is not one that comes at the cost of the well-being of the average Indian citizen. However, Allen’s more abstract view of Hind Swaraj ignores the real issues that Gandhi has with technology and the immoral relationship between the individual and the world that it cultivates. Stating simply that Gandhi is in favor of raising the standard of living without acknowledging what constitutes a better standard of living for Gandhi is antithetical to the substance of Gandhi’s critiques of modernity. The list of actions Gandhi advocates for in the conclusion to the text, as previously mentioned (Gandhi, 115), show a nuance to his views that is often overlooked, as he writes that different people in different circumstances cannot have the same contributions to a nationalist movement and cannot achieve individual swaraj in the same way.

Gandhi’s critiques of modern civilization and the enframing of consciousness that comes with it implies an impending struggle for dominance between what he sees as “true” and “false” civilization, exemplified in Hind Swaraj by the relationship between India and England. The relationship of the Indian and English people to their respective states is a complicated one. Gandhi sees this relationship as largely informed by the morality of India and the materialism of England. The English are united as a political body, with a shared national commitment to material and colonial gains: “As are the people, so is their Parliament. They have certainly one quality very strongly developed. They will never allow their country to be lost” (Gandhi, 33). For the English, country takes precedence over individual self-knowledge, where government rule transcends self-rule in significance. While the English are united in their materialism, the Indians are united in morality. Gandhi writes, “[W]here this cursed modern civilization has not reached, India remains as it was before…The English do not rule over them, nor do you ever rule over them” (Gandhi, 70). The Indian people’s refusal to accept the moral changes that come along with the supposed advances of modernity gives colonial rule no real power in these places in India. It is not tangible political power that Gandhi is concerned with here, but the power over a people, the ability to shape a culture as one sees fit, and this kind of dominance will never be achieved by the English once modernization is rejected.

This struggle between the moral and material civilizations is, in Gandhi’s view, inseparably tied to the principle of swaraj, pointing out a path to the future where the colonized India will prevail and the colonizing English are doomed. Swaraj, or self-rule, is described in the text as a process involving great discipline and becoming well-acquainted with oneself, a process which is possible for anyone but, due to India’s foundations as a largely moral civilization, this process is much more ingrained in their culture than it is in that of the English. Gandhi describes the necessity of this process of self-rule for his anti-colonialist goals, writing, “[S]uch Swaraj has to be experienced by each one for himself. One drowning man will never save another…If the English become Indianised, we can accommodate them” (Gandhi, 73). In the case of the English, Gandhi provides an avenue for the development of individual self-knowledge for them, if they are able to undergo the transformative process of self-rule. Again, moral gains trump political and material ones, as even a colonized India remains superior to England in its foundational qualities. The process of swaraj is not merely a spiritual act, however, as Shah points out: “Swa [meaning self] therefore emerges from the political necessity to challenge the English rule and awaken India’s self that was forgotten during the sway of English dominance” (Shah, 135). As she implies here, the advancement of the individual is a deeply political act in Hind Swaraj. The formation of an Indian identity, on a national as well as an individual level, is a more powerful tool in the independence movement than military mobilization and violence could ever be.

In his evaluation of English dominance over India, Gandhi identifies an unbalanced relationship between what he deems as true and false civilization. True civilization, which he associates with India, is moral and immaterial. The Enprimewglish, however, are both perpetrators and victims of the idolatry of false “modern” civilization. Colonialism as it is characterized in Hind Swaraj amounts to an attempt to spread the ideals of false civilization, and specifically to force Indians to give up their morals. At the root of this condemnation of modernity is the way that the technologies and institutions imposed by the English cause a restructuring of consciousness, as Shah argues. Allen furthers this argument by suggesting that Gandhi’s sweeping views on modern technology are largely metaphorical, and his real issue is with the way these technologies fuel the view that the ends justify the means. It is clear from Gandhi’s text that he sees these developments as immoral in and of themselves, but his central concern is the way that the Indian and English populations relate to the world around them. His arguments on modernity as the root of colonial rule reframe the struggle between the English and the Indians as two systems of morality grappling with each other, rather than the material domination of one state over another. This issue of the spread of modern civilization is at the heart of what is at stake for Gandhi: from his perspective, only time will tell if true or false civilization will win out in the end.

Works Cited

Allen, Douglas. “Is Gandhi’s Approach to Technology Irrelevant in the Modern Age of Technology?” Gandhi after 9/11: Creative Nonviolence and Sustainability, Oxford Academic Books, 2019, pp. 99-137. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199491490.003.0006

Gandhi, Mohandas. ‘Hind Swaraj’ and Other Writings, edited by Anthony Parel, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Lee, Theresa M. L. “Modernity and postcolonial nationhood: Revisiting Mahatma Gandhi and Sun Yat-sen a century later,” Philosophy & Social Criticism 41(2), 2015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453714554025

Shah, Esha. “Ethics of Technological Modernity: Reading Hind Swaraj towards Critiquing Craig Venter’s Synthetic Biology.” Re-reading Hind Swaraj: Modernity and Subalterns, edited by Ghanshyam Shah, Routledge India, 2013, pp. 123-141. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367818548