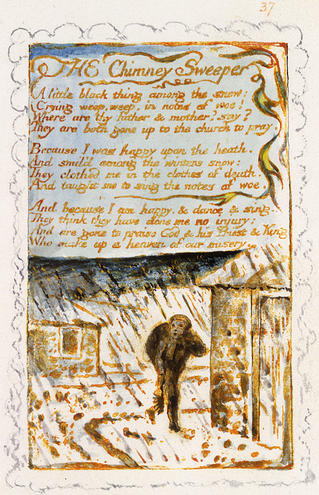

The Chimney Sweeper from Blake’s Songs of Experience, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

by Caleb Verma

Life in late 18th-century London was difficult, especially for those who were unfortunate enough to be stricken with poverty during this time of industrial revolution. Arguably, the people who suffered from this hardship the most were children, which is illustrated in both of William Blake’s “The Chimney Sweeper” poems. The subject of these poems is the titular chimney sweeps, children who have been sold by their families and forced to clean soot and ash from chimneys for a living. In these poems Blake portrays the suffering and adversity that these children face in their grim lives as chimney sweeps. In both poems, the speakers, who appear to be the young chimney sweeps themselves, offer their narratives concerning their abject conditions. While, on the surface, they appear to be simple stories describing the adversity a child chimney sweep faces in life, Blake’s poems offer subtle but profound criticisms on more complex issues, such as the concept of the family and the Church. In both of his “The Chimney Sweeper” poems in Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Blake exposes the horror and corruption behind the culture that produces these young chimney sweeps, and delivers a critical commentary on how and why such atrocities and injustices are allowed to take place.

The speaker in the Songs of Innocence poem gives the impression of being more optimistic than the speaker in Songs of Experience, who laments his unfortunate circumstances. The speaker in Songs of Innocence, the juvenile chimney sweep, doesn’t appear to mind having to work in terrible and dangerous conditions, and in fact, speaks unemotionally of his misfortune. He explains that “[his] father sold [him]” without any sense of resentment or pain, and plainly states that he sweeps chimneys and sleeps in soot. The speaker further expresses his feelings of indifference and uses them to calm other, more emotional chimney sweeps, such as Tom Dacre; when Tom cries while his head is being shaved, the speaker bluntly tells Tom to “Hush [and]…never mind it” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 7). This first chimney sweep does not appear to blame anyone for his deplorable way of life, as opposed to the second chimney sweep from Songs of Experience, who does the exact opposite; this chimney sweep directly states that his parents are to blame for his misfortune, explaining that “they clothed [him] in the clothes of death” (Songs of Experience, Blake 7) because he seemed too content with life. He further elaborates that they ignore his suffering, instead turning a blind eye and choosing to go to church as a means of distancing themselves from the situation. Furthermore, as opposed to the Songs of Innocence speaker, this “experienced” speaker acknowledges the severity of his circumstances, as he directly connects chimney sweeping to death through the description of his clothing, and expresses that he is miserable by singing “notes of woe” (Songs of Experience, Blake 8).

Despite the seemingly optimistic tone of “The Chimney Sweeper” in Songs of Innocence, however, there are several discrepancies in the hopeful speaker’s words, some of which lead to disturbing implications. First, the description of Tom Dacre’s hair being shaved contains Biblical imagery, as his hair is “curl’d like a lambs back” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 6); one of Jesus Christ’s titles is the “Lamb of God,” and the shaving of Tom Dacre’s hair can be seen as symbolic of his faith and relationship with God being severed due to being forced into such a forsaken position. His hair can also represent the darker symbol of a “sacrificial lamb,” however, something that is sacrificed for a greater purpose. These children can be seen as just such sacrifices, giving up their innocence and childhood to support their families, and being exploited to further the Industrial Revolution. More discrepancies can be found in Tom Dacre’s dream, such as when he envisions “thousands of sweepers…lock’d up in coffins of black” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 11-12), a metaphor for the soot-covered chimneys these children are confined to during work. Here, connections can be made to the Songs of Experience chimney sweep and his clothes of death, in that chimney sweeping is practically a death sentence for these children. Even in the seemingly optimistic Songs of Innocence poem, the speaker unconsciously acknowledges the horror of his occupation. Furthermore, the speaker in Songs of Innocence can be viewed as being ignorantly hopeful, as he uses Tom Dacre’s dream of green plains and rising upon clouds, a clear description of Heaven, as motivation for him and his peers to keep working without reluctance. The speaker states that “if [the boys] do their duty, they need not fear harm” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 24), indicating that if they continue to sweep chimneys, they will ascend to heaven and be happy in paradise. This statement is troubling in several aspects, such as how it proposes that harm will come to the children if they refuse to sweep chimneys, perhaps in the form of corporal punishment, or perhaps as a more supernatural consequence, such as Purgatory or Hell itself. Even in dreams, these children are told to work with full compliance, regardless of the perils of their occupation. Also, this statement implies that the only form of freedom for these children is through death, as he describes no other solution than to continue sweeping chimneys in hopes of a paradise in the afterlife. This emphasizes the futility and desperation of these children’s circumstances, as they do not even consider that help could come to them from other, more practical sources, such as other people, and instead resort to an uncertain utopia that they can only receive after they die. Furthermore, according to the speaker, access into Heaven will not even be granted to those who refuse to continue to work and sweep chimneys without question. Lastly, this statement is an example of the Church’s indoctrination of these ignorant children, as their only motivations, the utopia of Heaven and the punishment of Hell, are Church constructs. As impoverished children with little or no education, they are encouraged to repeat these widely known Christian beliefs to themselves and each other. This promise of a paradise as long as the chimney sweeps remain “good [boys]” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 19) and continue to work is a testament to the Church’s power and influence over 18th century London and the shaping of its society; in this poem, it appears that religion has in part facilitated this child abuse, and has even manipulated the children into believing that their working conditions must be tolerated in hopes for a better future. In this song of innocence, the gullible child speaker is deceived so that he continues to work with full compliance and no questions.

Both “The Chimney Sweeper” poems also contain a great deal of black and white imagery, although the symbolism and meanings of these colours are not consistent throughout. In the Songs of Innocence poem, the colour black, which is typically associated with concepts of darkness and evil, is used to describe the innocent chimney sweeps, covered in soot and ash. The menacing “coffins of black” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 12) still hold to the association with evil and black, however, and this may be to acknowledge that, while the children are still innocent beings even when covered with soot, they are not defined by chimney sweeping, and that the chimney sweeping industry is still very much corrupt; this corruption is shown to spread to the children, as displayed when the speaker tells Tom Dacre that his head is being shaved so that “the soot cannot spoil [his] white hair” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 8). Contrastingly, things that are white, such as the snow in the Songs of Experience poem, harm the child chimney sweep, thus disturbing the connection between white and goodness. This connection is complicated further through the complex figure of the Angel with his “bright key” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 13) and the concept of Heaven. While the idea of a paradise, where the children can be “naked & white” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 17) offers the speaker and his friends a sense of hope and motivation to be optimistic, it also prevents the children from questioning their horrid working conditions. Also, while this sense of hope can keep the children happy to some degree, this joyful optimism can be misinterpreted as an absence of suffering by others, as is the case with the chimney sweep in Songs of Experience, as his parents “think they have done [him] no injury” (Songs of Experience, Blake 10) because of his happiness. While the concept of Heaven motivates the children throughout their miserable existences, it hinders any change being made to their disastrous conditions. This inconstancy of the symbolism of black and white further emphasises that the situation of a child chimney sweep is highly ambivalent and complex.

Finally, the Songs of Experience poem, while on the surface seems to have one primary voice, the voice of the child chimney sweep in fact contains the contradictory voice of another, more mature speaker. This second, experienced voice is clear in the first three lines where they address the child in the snow. This mature speaker acknowledges the child’s suffering, describing the chimney sweep crying in “notes of woe” (Songs of Experience, Blake 2), and questioning where his guardians are. While the poem seemingly shifts speakers to the child permanently after the third line, these critical criticisms of concepts an innocent child would fail to grasp remain throughout. This second, underlying voice is most apparent in the final stanza, where criticisms of concepts such as family and the Church are delivered. The mature speaker criticizes the Church, poignantly stating that they “make up a heaven of [the children’s] misery” (Songs of Experience, Blake 12). This can be viewed as a radical deviation from the Songs of Innocence poem where, despite his suffering, the speaker saw religion as a source of hope, rather than the origin of his pain. The criticism of the child’s parents is also displayed, when the speaker states that they have “gone up to the church to pray” (Songs of Experience, Blake 4) instead of caring for their child, another deviation from the first poem, where the speaker doesn’t blame his father for selling him into chimney sweeping. While this second, mature speaker may seem to be have good intentions in trying to condemn what they feel are the sources for the child’s pain, they completely misrepresent the child in the process. The child’s voice contradicts the mature speaker’s, explicitly stating that, despite his suffering, he is happy. By going on a tirade against the Church and the child’s family, the mature speaker completely forgets the essence of a child, which is innocence. Despite his hardships, the young chimney sweep is still hopeful in the second, more cynical poem. In the process of searching for people to blame for the child’s suffering, the mature speaker harms the child himself, disregarding his feelings and, consequentially, failing to understand and find a solution for this child’s pain.

While these poems have no single, “true” interpretation, their lack of a definitive solution for these poor chimney sweeps paradoxically gives them purpose; they inspire discussion on finding a better future for these impoverished children, and bring optimism to an otherwise grim situation. They encourage questioning of important concepts such as child abuse, the Church, family, the essence of childhood, and the morals and values of the readers themselves. After all, it is “your chimneys [they] sweep” (Songs of Innocence, Blake 4).

Works Cited

Blake, William. Songs of Innocence and of Experience: Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. London: Oxford UP, 1977. Print.