by Josephine Ansley

In a world fraught with global inequalities, political instability, and the rise of corrupt populist authoritarian leaders one may wonder whether we have really progressed as a society or if we are closer to devolving into the Hobbesian state of nature. Hobbes’s ultimate dilemma in Leviathan is how to remain out of the state of nature and unite a divided multitude to ensure collective liberty. In the latter half of the 20th century, we have come to regard democracy as the best way to attain freedom and liberty for all, and we view it as the ideal political system to mitigate civil unrest and political instability. In recent years; however, democracy in practice has proven to be ineffective in dealing with complex domestic and international issues. Hobbes would attribute this to the pitfalls of democracy where everyone is afforded equal participation, which can upend society and create civil war. It is precisely Hobbes’s concern with these internal divisions that makes him justify the need for a sovereign to save people from their fellow citizens. Hobbes’s paradoxical view of liberty leads him to envision a social contract that unites the disorganized multitude under a sovereign power. While Hobbes’s conception of a sovereign appears contradictory to liberty, this paper posits that his notion of the sovereign aligns with his desire to secure liberty. For Hobbes, liberty is only attainable with the development of the social contract, the formation of the sovereign, and through centralizing power within a monarchy to overcome the perils that internal divisions and corruption pose for the commonwealth.

Hobbes’s aim in Leviathan is to develop a social contract that helps centralize power to ensure political stability and prevent internal divisions and civil war. In order to understand Hobbes’s justification for a monarchical sovereign over democratic rule, we need to comprehend how the sovereign comes to fruition throughout the development of Hobbes’s social contract. The Finnish Social Science and Philosophy scholar Jakonen Mikko notes that for Hobbes “the question between the multitude and the social contract is a case between absolute power (sovereignty) and the total absence of power (the multitude)” (Jakonen, 2016, p.97-98). Hobbes is aware that in the absence of a social contract where people join to form a sovereign, there is no opportunity for mutual security and prosperity (Jakonen, 2016).

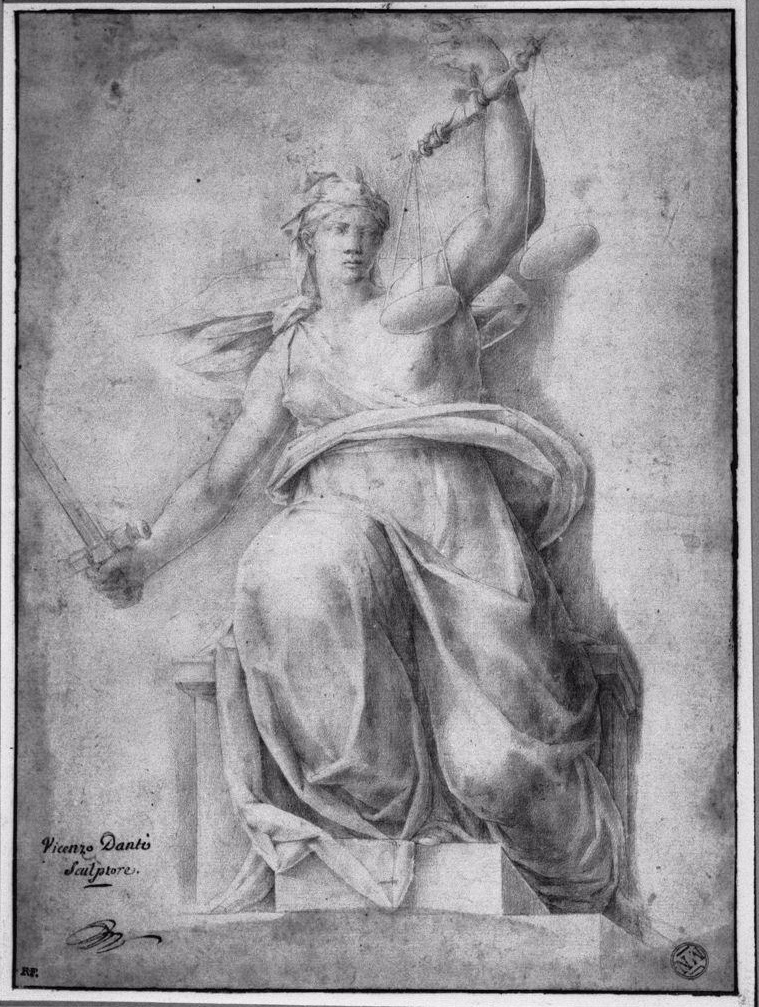

Hobbes advocates that the ultimate way to provide social security and uphold liberty is through the centralized power of a sovereign, which is evident before the text even begins with the frontispiece of Leviathan. The frontispiece visually illustrates “the sovereignty is … an assembly of the people” (Hobbes, p.116). It is in the best interest of the sovereign to support and provide a good life for its subjects, as the power of the sovereign is derived from the power of the people. If the sovereign arbitrarily harms its people, then by extension, it simultaneously harms the institution itself. In analyzing Hobbes’s contradictory stance of a sovereign’s role to procure liberty Jakonen asserts that in the process of forming a social contract, “the anarchic and chaotic multitude is transformed into a political subject, the people” (Jakonen, 2016, p.92). It is the people that “represent the first form of political unity and is the basis of sovereignty” (Jakonen, 2016, p.92). So, while the sovereign is built on democratic ideals of the multitude coming together to form a political entity, Hobbes does not condone democracy as a legitimate form of government in action (Jakonen, 2016). For Hobbes, “the multitude can never be a political subject” as it must always remain “an object of governance” (Jakonen, 2016, p.115). In the covenant between the people and the sovereign, the individual ceases and is now a part of a larger political entity. The “sovereign power represents the power of individuals, which amounts to nothing in the multitude as the individuals are hindered by each other” (Jakonen, 2016, p.101). The sovereign represents the power of the people, not the power of the multitude. Sovereignty is the “omnipotence of the people over the multitude, or in other words, the omnipotence of the political subject over the apolitical mass of individuals” (Jakonen, 2016, p.101).

It is through tacit consent that the apolitical multitude forms the sovereign. The people transfer all rights and civil liberties to the sovereign, except their inalienable right to life. In return the people are assured social security and peace. Through this consent all people have agreed to a covenant with the sovereign. However, the sovereign makes “no covenant with [its] subjects” because as soon as this occurs it decentralizes power and then people are forced to make “several covenant[s] with every man” and divide their loyalties, and when this internal division is present the state is vulnerable to corruption (Hobbes, p.111). Therefore, a citizen must make a covenant “with the whole multitude, as one party” represented by the sovereign (Hobbes, p.111). It is easier to have one covenant with an institution than with many people because people are self-interested, driven by their desires, and more susceptible to breaking covenants. Hobbes justifies the sovereign by condemning human nature as inherently self-interested and aggressive, thus establishing the need for the sovereign as it remains an impartial entity incapable of being corrupted of its rationality.

If the sovereign was accountable to the people by a formal covenant, then everyone would have an equal say in how their state would be governed. For Hobbes, this would decentralize power and destabilize the state. The sovereign is the result of the covenant so there can be “no breach of covenant on the part of the sovereign” (Hobbes, p.111). It is only people that can break “their covenant [to the sovereign and this] is injustice” (Hobbes, p.111). The sovereign acts as a representative of the people as they have transferred all their power and rights to it, so if the subjects oppose decrees made by the sovereign, they break their covenant and are therefore unjust. If an individual refuses to consent to the sovereign and adhere to its laws they will be “left in the condition of war” they were in before the protection of the sovereign (Hobbes, p.112).

In order for the sovereign to procure peace it must yield “the public sword” (Hobbes, p.112). The state must make laws and punishments because “where there is no common power, there is no law, where no law” no justice (Hobbes, p.78). The sovereign assures safety to its subjects through promising that any enemy of the state or individual within the state will be punished. It is through the sovereign’s sword that peace is maintained because what “incline[s] men to peace [is] fear of death (Hobbes, p.78). The public sword is vital because without consequences covenants are easily broken, as covenants are nothing but “words and breath, [they] have no force to oblige, contain, constrain, or protect any man” (Hobbes, p.112). Laws in and of themselves have no inherent power “to protect … without a sword in the hands of a [sovereign] … to cause those laws to be put in execution” (Hobbes, p.138). Hobbes even advocates that civil liberties “depend on the silence of the law” (Hobbes, p.143). The sovereign makes people adhere to peace because of the absolute power it yields to punish.

In the development of Hobbes’s social contract, he continues to advocate that the only way to secure peace and prosperity amongst a divided multitude is to invoke a sovereign, as “the sovereign power is the outcome of a metamorphosis in which the plurality of wills are condensed into a single one” (Jakonen, 2016, p.99). Hobbes asserts that for people to enjoy freedom and civil liberty, a sovereign is essential or else they will descend into the state of nature. Hobbes defines the state of nature as “the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war, and such a war as is of every man against every man. For war consisteth not in battle only, … but in the known disposition” (Hobbes, p.76). Hobbes contests that the state of nature is ever present, which is why there must be a sovereign in place to guide society. Scholar Seyla Benhabib, discusses that Hobbes’s authoritarianism coincides with his belief that “as long as the sovereign can guarantee a peaceful and comfortable existence by protecting the subjects’ lives, the pursuit of all higher goods such as a life of ethical virtue and political glory … [and] a life of freedom as equals living under the rule of law … should be abandoned, since they [have] led to conflict” and anarchy (Benhabib, 2022, p.234). On the surface one could argue that Hobbes’s notion of the sovereign infringes on people’s individual rights and freedoms. However, his view is that if people’s rights are not constrained by the sovereign, then they are the ones who infringe on other peoples’ rights, which creates internal conflict and war.

Hobbes is more concerned with internal divisions as a threat to the commonwealth than he is with corruption. This is precisely why he advocates for monarchical rule over democratic rule. Hobbes regards democracy as inferior as it relies too much on the multitude and the “main reason why the multitude cannot ever be a political subject, a political entity or a commonwealth is that the multitude does not have one will, but instead a plurality of wills” (Jakonen, 2016, p.96). A multitude can never be an effective political body because its interests are divided. Hobbes states that “a kingdom divided in itself cannot stand” because without a centralized power the political body becomes ineffective to govern the people (Hobbes, p.115). In democracies, there is not enough distinction between those who are governed and those who govern. This leads to ineffective politics and as a result the state is susceptible to leaders who can persuade the public to serve their own advantage (Jakonen, 2016). Democracies breed populism which creates political instability (Jakonen, 2016). Hobbes views democracy as more susceptible for rulers to coerce and manipulate people into decisions that go against their best interests, as “in a democracy no one is safe from the cruelty of demagogues and orators” (Jakonen, 2016, p.106). Democracy is more susceptible to corruption because “the democratic mode of government strengthens populist leaders who rhetorically mislead both common and uneducated people to the point where demagogy turns into chaos and the logic of the multitude gets to reign” (Jakonen, 2016, p.92). Once the anarchic multitude is unleashed it contributes to the dissolution of the commonwealth and the sovereign that secures order in society (Jakonen, 2016). Hobbes is concerned that democracy promotes a concentration of power vested in a handful of leaders instead of the general public. Following Hobbes’s negative view of human nature, that we are self-interested, he believes democracy only leads to more corruption as leaders serve to their own advantage at the expense of the greater good. Hobbes advocates that unlike a democracy, in a monarchy “the private interest is the same with the public” (Hobbes, p. 120). In a monarchy there is no distinction between public and private interests as what is good for the people is advantageous for the state, as “no king can be rich, nor glorious, nor secure” if their subjects are poor (Hobbes, p.120).

Since the people form the sovereign, in Hobbes’s view, there is no concern with the concentration of power within a monarchical sovereign because unlike a democracy, the sovereign acts as a united representative of all the people’s interests, so it is less vulnerable to corruption than a democracy where a few powerful leaders hold all the power under the illusion of being in service to the people. Populist leaders can indoctrinate the masses and “corrupt judgement [which] impedes reason and produces faulty conclusions” which is why Hobbes justifies a sovereign to guide the easily corrupted multitude (Blau, 2009, p.603). While Hobbes acknowledges people are capable of reason and rationality, people are corrupted by their desires and emotions which are “strong and permanent” and prevents them from governing themselves (Hobbes, p.13). Democracies offer the ideal conditions for corruption as the most dangerous thing for a state is “the combination of [the] passionate stupidity of the multitude and [the] eloquence of … demagogues” (Jakonen, 2016, p.109).

King’s College professor, Arian Blau outlines different types of corruption and relates it to Hobbes’s political theory. Blau highlights that cognitive corruption is of the utmost concern for Hobbes as it creates distorted judgement which “can lead to political corruption (bribery) or sedition (factional strife), fomenting civic unrest” (Blau, 2009, p.603). It is through leaders indoctrinating the masses that corruption ensues. If rulers can harness the multitude’s desires and prey on their fears, they are going to be able to cognitively corrupt the people. Once a leader controls people’s thoughts, they control their anti-civic actions. An absence of cognitive corruption is crucial to achieve political order. Hobbes’s account of political order is that “citizens will obey the sovereign if they reason clearly without being infected by fractious dispositions; otherwise citizens are corrupt” (Blau, 2009, p. 605). Hobbes views internal strife as the outcome of rebellion as “sedition [is] the state of rebellion occurring after widespread cognitive corruption” (Blau, 2009, p.614). For Hobbes, corruption refers to any anti-civic action. This is precisely why the sovereign cannot become corrupt, as in theory the ideal monarchical sovereign will remain in service to the people and in pursuit of its civic duties of securing the liberty of the state.

Hobbes acknowledges that a “sovereign power may commit iniquity, but [never] injustice” because injustice is breaking covenant which the sovereign is not accountable to. Another reason Hobbes does not foresee the sovereign becoming corrupt is that he believes most sovereign powers will make laws in accordance with the laws of nature. If they are in line with nature, they can never be corrupt for “nature itself cannot err” and if the sovereign is aligned with nature, it too will never err (Hobbes, p.19). For Hobbes if the sovereign errs, it is for God to judge, rather than the people as the sovereign is only accountable to God. Corruption leads to the dissolution of the commonwealth which by default leads to the state of nature and civil war. Since the sovereign’s objective is securing liberty for its subjects, any actions the sovereign makes will be in service to “common peace and defence” (Hobbes, p.115).

In further analysis of Hobbes’s reverence for monarchical rule over democratic rule, Jakonen’s analysis derived from Hobbes’s Elements of Law elucidates Hobbes’s understanding of corruption in democracy stating that due to democracies’ division of political power “there are always new people coming to seek the benefits of power and this easily leads to high costs of bribery and corruption that cannot be done without exploiting the citizens. [However,] in [a] monarchy, corruption takes place within reasonable limits” (Jakonen, 2016, p.110 as cited in Hobbes). Blau explains that Hobbes despises the notion of a mixed government, that combines the sovereign and the multitude and regards it as self-defeating (Blau, 2009). The sovereign’s “great authority [is] indivisible” and its power is derived from being a singular political entity (Hobbes, p.116). For Hobbes, the decentralization of power is the greatest failure of democracy, and according to Jakonen, Hobbes contests “the democratic sovereign has much less power than the … monarchic sovereign, since the power has been dispersed all over the body politic” (Jakonen, 2016, p.115).

The ultimate way to safeguard people from harming one another is through a monarchy. Hobbes deems a monarchical sovereign a more efficient way to govern in terms of centralizing power. Since, there is “a general inclination of all mankind, a perpetual and restless desire of power, that ceaseth only with death,” every person is always looking for more power in life even if it at the expense of another (Hobbes, p.58). This perpetual quest for power creates internal factions and as Jakonen notes “leads to politics where the sole aim is power and the wellbeing of the commonwealth is … forgotten” (Jakonen, 2016, p.113). In defense of an omnipotent sovereign Jakonen notes that Hobbes underscores that the “biggest threat to [one’s] safety and well-being is the unlimited action and motion (absolute liberty) of each and every one” (Jakonen, 2016, p.96). Hobbes invokes the sovereign, thus restricting individual freedom to ensure collective freedom and prosperity. In this sense Hobbes is regarded as a liberal, as the notion of restricting individual freedom for societal freedom is a liberal value. John Stuart Mill, one of the most influential liberal thinkers of the 19th century is known for his principle of liberty that stipulates precisely what Hobbes first proposed in his social contract theory. Mill’s principle of liberty is that everyone should be free to pursue their own means of liberty so long as it does not infringe or harm another’s capacity to achieve freedom (Love, 1998). While Hobbes and Mill would disagree on the extent of our freedom, Mill’s principle of liberty supports Hobbes’s notion of a sovereign to regulate our mutual relations because without an absolute power we would infringe on each other’s liberty and each other’s inalienable right to self-preservation.

Hobbes is critical of the democratic process as it relies on constant public deliberation and elections which suspend state power and create instability. In doing so, the state can no longer protect its citizens resulting in civil war (Jakonen, 2016). Due to constant democratic deliberation democracy fails at protecting our one inalienable right to life, so “even though the birth of the people is the birth of the sovereign power and in this way democracy is the basis of any kind of absolute sovereign government, for Hobbes democracy is the worst kind of government for a commonwealth” (Jakonen, 2016, p.114). In the end, Hobbes always favours a united power over one that seeks approval from a multitude.

To ensure internal harmony and safeguard itself from internal strife the sovereign must have absolute authority to choose all “counsellors, ministers, magistrates, and officers” because otherwise people in government have differing opinions from the institution, which creates internal conflict and destabilizes the state (Hobbes, p.114). In democratic states judicial and political decisions are made by the multitude and are not made by a united political entity, which creates ineffective governing. Since democracies are vulnerable to corruption Hobbes justifies that the soul “judicature of all controversies” should be resolved by the sovereign so that justice is upheld to the institution’s standards (Hobbes, p.115). The sovereign is the ultimate authority establishing the necessary conditions for peace and ensuring collective security with every decree and action. It is for “the sovereignty to be [the] judge of what opinions and doctrines are averse” as a sovereign cannot let its people be corrupted by their emotions and fears because this causes people to become irrational, which leads to war (Hobbes, p.113). Hobbes is aware of the catastrophic effects of false doctrines and its ability to breed civil unrest, so that is why it is up to the “sovereign power to be the judge … of opinions and doctrines, as a thing necessary to peace, thereby to prevent discord and civil unrest” (Hobbes, p.113-114). For Hobbes it is always about maintaining political unity.

Democracy, for Hobbes, is perilous as it is too interconnected to rule by the multitude and mob rule. The only time where Hobbes fears the destabilizing effects of absolute power is in relation to the power of the people — the mob. Hobbes is concerned with the prospect of the people becoming corrupted by their irrational thoughts and emotions resulting in anti-civic actions. Hobbes argues that “rebellion is but war renewed” because it develops into anarchy (Hobbes, p.208). Hobbes takes away citizens’ legal rights to rebel. While this appears contradictory in protecting liberty, this prohibition of rebellion is invoked to ensure state stability. So, while this prohibition infringes individual liberty, ultimately, it ensures security of the state and by default ensures collective freedom. Hobbes justifies this prohibition of rebellion to prevent political instability because if everyone becomes corrupted of reason and indoctrinated with rebellious desires, then society succumbs to the state of nature. Hobbes is aware that it is not merely enough to satisfy people’s basic needs. The sovereign needs to provide people with good lives so that they do not become “weary of” life and rebel at the source of their discontent – the sovereign (Hobbes, p.82). Hobbes is cognizant of the threat the mob poses if unsatisfied, therefore the sovereign must appease the majority’s needs. Hobbes even goes as far to promote the idea that men who are unable to support “themselves by their labour” due to injury are “to be provided for … by the laws of the commonwealth” (Hobbes, p.228). If the sovereign “neglect[s] the impotent” the probability of war and civil unrest increases (Hobbes, p.228). Appeasing public interest is essential to mitigating sedition and political instability. The reason Hobbes is preoccupied with providing a good life for everyone is because if people die at the hands of the sovereign that means the sovereign has impeded the ultimate right to life, and if that occurs the state of nature has prevailed.

In the development of Hobbes’s social contract, he concludes that the sovereign is the ultimate way to centralize power and is an integral part of procuring peace. Hobbes advocates that the sovereign is imperative as “the end of this institution is [the end of] peace” (Hobbes, p.113). Hobbes deems monarchical sovereigns the way to unite a multitude to submit to its authority. He regards democracies as cesspools for corruption and internal divisions. It is democracies’ vulnerability to corruption that results in mob rule, ineffective governing, and the erosion of the commonwealth. Democracy further exacerbates the susceptibility of civil war. While Hobbes is concerned about corruption, he is more concerned about internal factions which lead to the state of nature. Hobbes does not believe that absolute power corrupts absolutely and argues it is crucial to maintain social order. While at first, Hobbes’s claims of the sovereign’s absolute power appear at odds with his conceptions of liberty, in further analysis they are aligned as they are both in service to the procurement of security and peace. Ultimately it is through absolutism that the “generation of [the] great Leviathan” is born (Hobbes, p.109).

Works Cited

Benhabib, S. (2022). Thomas Hobbes on My Mind: Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 89(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2022.0015

Blau, A. (2009). HOBBES ON CORRUPTION. History of Political Thought, 30(4), 596–616. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/hpt/2009/00000030/00000004/art00002

Hobbes, T. (1994). Leviathan: with selected variants from the Latin edition of 1688 (E. Curley, Ed.). Hackett Pub. Co. (Original work published 1668)

Jakonen, M. (2016). Needed but Unwanted. Thomas Hobbes’s Warnings on the Dangers of Multitude, Populism and Democracy. Las Torres de Lucca : Revista Internacional de Filosofía Política, 5(9). https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/52790

Love, N. S. (1998). Dogmas and Dreams: A Reader in Modern Political Ideologies. In Google Books. Chatham House Publishers. https://books.google.ca/books/about/Dogmas_and_Dreams.html?id=lqIUAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y