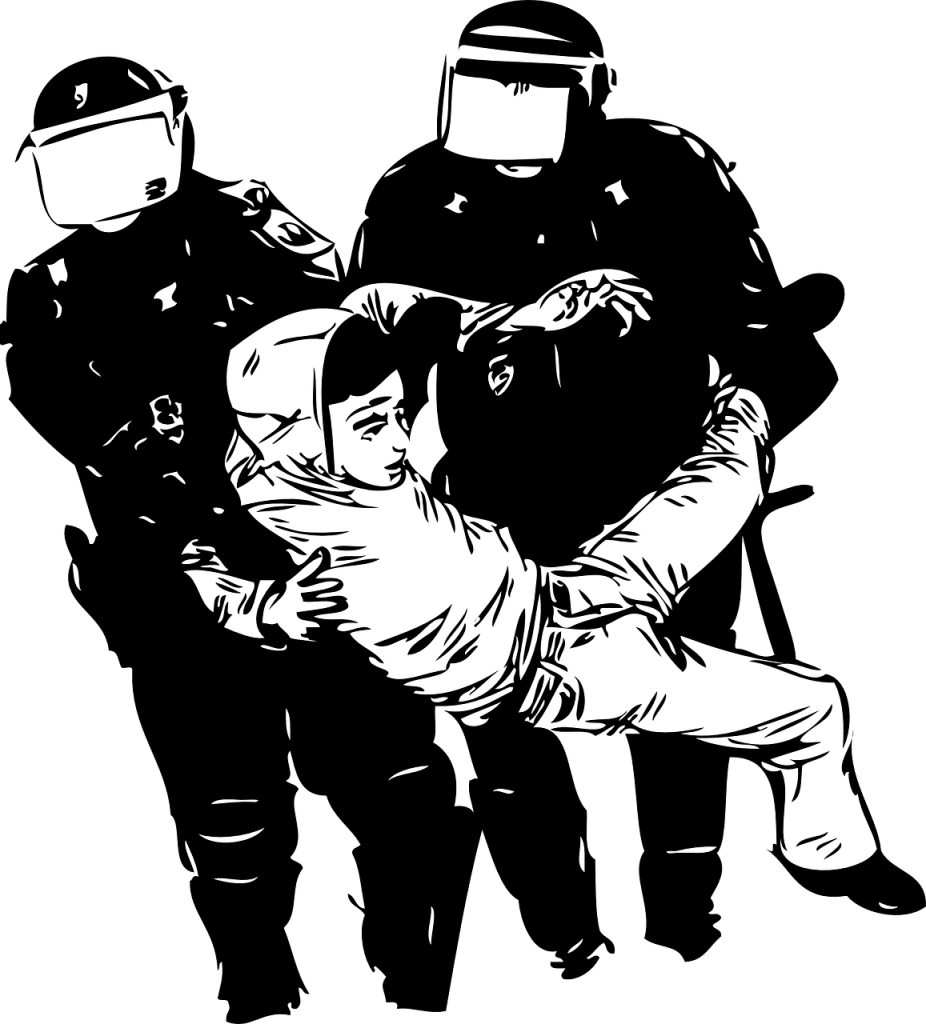

Photo via Pixabay

by Annette Idiagbor

In hopes of educating his teenage son on the everyday struggles black people experience, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes of his own personal life experiences in his memoir Between the World and Me. Presenting his revelatory experiences from childhood and adulthood, Coates struggles to understand how the destruction of black people is justified by the divide between the perceived races of black and white. He suggests that being raised in the United States of America, with its history of exploitation and savagery towards black bodies, has robbed him of control over his own body and censored the positive aspects of black history. Upon asking himself “how one should live within a black body,” Coates searches for the answer “in classrooms [and] out on the streets” (12). America’s controlling influences persist despite Coates living in a generation with significantly more freedoms for black people, and he promotes the idea that West Baltimore’s unforgiving streets and unimaginative school system act as figurative shackles on explorations into racial injustice. The ongoing destruction of black bodies in America inspires questions about the cause of this injustice, along with inquiries into the potential solution. Between the World and Me explores how the streets and schools both work to conceal the unfairness of black citizens’ reality, which dissuades the push for monumental changes and characterizes the ongoing oppression of black people as being commendable. This systematic subjugation ultimately acts as a trap that demands total assimilation to the rules and structures in place. The personal curiosity towards a better situation for black people demonstrated by how Coates defies this message of passive acceptance. Coates portrays how total conformity and abandonment of racial inquiries are presented as being the only means of survival for black citizens in America, and how his deviance from these groups’ restrictive regulations had the potential to place his life in jeopardy.

The main motivation behind Coates’s question of how to live free as a black citizen comes from his observations of black bodies being destroyed. He notes how “black people controlled nothing, least of all the fate of their bodies” (62) in America. Rather than decide their own destiny, black Americans are subjected to receiving unfair treatment and having their lives ended in a brutal manner. Coates lists examples of black bodies that his son has seen unjustly destroyed in order to emphasize the magnitude of this issue, such as: Eric Garner, a black man strangled for selling cigarettes; Renisha McBride, a black woman shot for knocking on a door; and Tamir Rice, a black child shot for having a toy gun in a park (9). He does not comfort his son when he cries at the acquittal of a police officer who shot an unarmed black teenager, instead hoping that his son will “know now, if [he] did not before, that the police departments of [America] have been endowed with the authority to destroy [black bodies]” (9).

Coates notes how growing up in Baltimore, he witnessed violent behavior and customs that “attested to all the vulnerability of the black teenage bodies” (15). A key reason for the presence of such violent behavior is gangs. The Baltimore City Criminal Justice Coordinating Council presented a plan to reduce gang violence in 2006, and reported that “the majority of identified gang members in Baltimore are African American” (5). This proposed plan defines a gang as “three or more persons . . . who individually or collectively . . . [engage] in criminal activity which creates an atmosphere of fear and intimidation” (4). Direct participation in gang activity is not necessary, since the atmosphere created on the streets as a result of such activity affects the entire city—whether someone is a gang member or not. Between the World and Me seems to address this notion of an uneasy atmosphere in Baltimore’s streets, as Coates describes them as containing an “array of lethal puzzles and strange perils” (21). Using the term “lethal” to describe the phenomenon of the streets emphasizes black Americans’ fear over the security of their bodies, while vocabulary like “puzzles” and “strange” convey the uncertainty that comes with establishing security in the streets. While observing his son’s disappointment at the verdict of not guilty, Coates notes that “for all [their] differing worlds,” his feelings about black injustice “[were] exactly the same” at his son’s age (21). He observes how parents raising children in Baltimore were scared to lose a child “to the streets” (16), and that they viewed the “safety net of schools” (17) as the best way to protect their children. Coates writes how his life experiences led him to question the apparent “safety” that schools provide from the dangerous streets, and identifies how these separate groups are ultimately working together to trap black Americans and force them into accepting a life of oppression.

The first step taken by schools to set this trap is to deter students from advocating for a new reality. They do so by idealizing a concept Coates calls the Dream, where the privilege and lack of harassment directed towards people who believe they are white accentuates the benefits “of acting white, of talking white, [and] of being white” (111). Baltimore’s high schools methodically present white people in a more positive and dominating light compared to black figures, which makes the suffering of black people appear to be nothing out of the ordinary. Coates notes how black excellence was never celebrated “in the textbooks [he had] seen as a child,” while “everyone of any import . . . was white” (43). Coates does not state that texts in general were absent of positive black representation, but only that they were not exposed to him “as a child” in high school. His future discovery of “virtually any book ever written by or about black people” (46) at Howard University stresses how the issue is not strictly the lack of black texts, but Baltimore’s failure to incorporate such works into their curriculum. Coates’s discovery of unconventional sources of knowledge at Howard University—such as hip-hop and rap music—shows how high school’s prohibition of non-academic sources provided “an education rendered as rote discipline” (25). Along with the issue of white history being presented as the “serious history” (43) in Baltimore’s curriculum, Coates criticizes classrooms for their tendency to stifle the curiosity of students. His claim that “the classroom was a jail” (48) shows how he found the school environment to be constricting, and this prison-like quality is something Coates attributes to all schools alike. Despite his arrival at Howard University initially feeling like an experience where “the black world was expanding before [him]” (42), Coates confesses that he ultimately felt his interrogation of black history remained “bound . . . by Howard” since “it was still a school, after all” (48). Along with a lack of black celebration and an emphasis on coveting the Dream, the classroom environment remains unable to facilitate a healthy drive to seek out answers regarding black Americans’ past and possible future.

These failures to foster curiosity and present aspirations besides the Dream are seen in Baltimore’s streets as well, with residents being just as susceptible to this methodical suppression of personal ambition. Looking back on his childhood from an adult perspective, Coates notices that “the Dream seemed to be the pinnacle . . . [and] the height of American ambition” (116) in Baltimore’s streets. Residents would therefore refrain from asking “what more could possibly exist . . . beyond the suburbs” (116), and abstain from any potential inquiries into roads leading beyond this pinnacle. Coates explains that the Dream appeared to be “somewhere beyond the firmament [and] past the asteroid belt” (20). The use of vocabulary like “beyond” and “past” when speaking in terms of location, along with the feeling of uncertainty associated with the term “somewhere,” emphasizes the sizable distance perceived between the streets and the Dream. By depicting the Dream as the ultimate goal and placing the finish line so far away, the streets make efforts to escape and reach the suburbs seem futile. Even when such attempts are made, Coates writes how in an attempt to pursue the Dream:

[black people] rose up out of the ghettos . . . [and] went out into the suburbs, only to find that they carried the mark with them and could not escape. Even when they succeeded, as so many of them did, they were singled out, made examples of, transfigured into parables of diversity. (142)

The Dream is ultimately unavailable to those who carry “the mark” of a black American. Any achievements will be belittled or distorted to reinforce negative stereotypes, since black citizens associated with success are “singled out” for deviating from the Dreamer’s idea of the general black population as consisting of poor and violent people.

Just as high school encourages students to conform to the rules and restricted curriculum in place, the streets persuade residents and gangs to respect their unique laws and accepted customs. Coates identifies fixed street “laws [that] were essential to the security of [his] body” (24), such as memorizing restricted blocks and reading underlying tones of speech and body language. He notes that “fully one-third of [his] brain was concerned” (24) with flipping through the unofficial rulebook of the Baltimore streets at all times, since conflict and death “could so easily rise up from nothing” (20). This behavior being mandatory for survival appears to hamper Coates’s investigation; he believes “that third of [his] brain should have been concerned with more beautiful things” (24), such as visions of success beyond the Dream and a healthy skepticism about escape from the streets being discouraged. The street’s disapproval of pursuing the unattainable Dream, along with schools teaching the importance of exalting the Dream, demonstrates the first step of hindering black liberation from America’s control.

After convincing residents and students to embrace the Dream’s allure, Coates claims the next step is dissuading revolution and glorifying black oppression. He writes that being “a curious boy” (26) sparked his interest in the racial divide, and he admonishes how “schools were not concerned with curiosity . . . but with compliance” (26). He felt this restriction of curiosity in high school but also in college, as his quest for knowledge at Howard University “could not match . . . the expectations of professors” (48). After spending time in the university library reading black texts, Coates concludes that “the Dream thrives” on “limiting the number of possible questions” (50). Advocating for systematic change requires questioning the current system, and schools fear the resulting answers will potentially rattle the Dream’s foundations. When young Coates’s question about the unwarranted “assault upon [black] bodies” (26) went unanswered by his teachers, he conducted research as an adult that revealed the Dream rests on “the right to break [black bodies]” (105). Coates suggests that his high school was “drugging [students] . . . so that [they] did not ask” (26) this dangerous question; revealing the answer would threaten the Dream’s integrity, or motivate black citizens to demand that it be abolished. One of the non-academic sources Coates cites to support his opinion that concealment is a toxic drug is rapper Nas, whose lyrics claim that school is a “poison” (26). Continuing to write based on his belief that schools obscure black oppression, Coates proposes they instead distort truths in hopes of romanticizing the plight of black Americans. His high school review of the Civil Rights Movement appears “dedicated to the glories of being beaten on camera” (32), and he ponders how schools send students “out into the streets of Baltimore, knowing all that they [are], and then speak of nonviolence” (32). Coates assumes they purposely turn a blind eye to the streets leaving black youth “naked before the elements of the world, before all the guns, fists, knives, crack, rape, and disease” (17). Rather than expose these circumstances as intolerable, the school “urged [Coates] toward the example” set by black activists of how “[loving] the worst things in life” is the epitome of black strength and courage (32). By sedating persistent questions and claiming that the victories of black history resulted from passivity, schools are able to convince students that the current plight of black people is admirable for its lack of active resistance.

This romanticization of black oppression also exists in Baltimore’s streets, as gang members view the constant danger of their environment as a testament of their power. This belief that survival equals control is a delusion, since black people “did not design . . . do not fund . . . and do not preserve [the streets]” (22); the streets are a killing field “created by the policy of Dreamers” (111), making them “an elegant act of racism” (110). In hopes of glamorizing the previously mentioned atmosphere of fear and intimidation that results from gang activity in Baltimore’s streets, Coates notes how neighbourhood boys dress in extravagant clothing and concludes that this clothing is meant to act as “armor against their world” (14). The “ghosts of the bad old days” where black people were lynched and held no possessions make these boys fear that the past could become their present, and thus expensive clothing allows them to feel “in firm possession of everything they [desire]” (14). Despite these observations and their subsequent conclusions, Between the World and Me lacks any record of Coates asking crews why they chose to dress and act this way, and thus the claim that it was distinctly rooted in fear is not the definitive motive—only a theory from the author. Coates admits that he himself “was afraid” (14) in Baltimore’s streets, and thus his declaration that everyone on Baltimore’s streets was “powerfully, adamantly, dangerously afraid” (14) may be him projecting his emotions onto others. Just as nakedness to the harsh elements of the violent streets showed the destruction of the black body, it also demonstrates the streets’ romanticization of bodily harm to black Americans. Gang members aim to “prove the inviolability . . . of their bodies through their power to crack knees, ribs, and arms” (23). This behaviour demonstrates the streets’ belief that being able to injure others is a symbol of personal power and security.

Just as black suffering is taught to be an admirable display of nonviolence in schools, and interpreted among gang members as a display of strength, residents who are not affiliated with street gangs also approach black suffering with a “fantastic gloss” (54). Coates utilizes the story of Queen Nzinga’s interaction with a Dutch ambassador to show how the streets can push a distorted narrative. He writes how “the Dutch ambassador tried to humiliate [Nzinga] by refusing her a seat,” and the Queen responded by ordering her advisor to “make a human chair [out] of her body” (45). While this story depicts a body being broken down in order to serve the needs of someone else—just as black Americans are broken down to support the Dream—the focus is placed on the advisor’s versatility in support of the Queen. Coates criticizes both the schools and streets for this glorification of black destruction, since there is “no nobility in falling, in being bound [or] in living oppressed” (55). After promoting the Dream as desirable and glamorizing black Americans’ current plight of systematic injustice, the streets and school work in tandem to enact the final step in consolidating the preservation of black disembodiment.

After accepting the Dream’s foundation of black persecution and dignifying this suffering as a symbol of black strength, Coates reveals how the aforementioned rules of accepting black suffering and ceasing to advocate for a new reality create a system that abolishes any opportunity to seek reformation. The road to alleviating black suffering is hidden “behind the smoke screen of streets and schools” (28), and together their rules act as “the curtains” (28) obscuring any possible future of regaining bodily control; the terms “smoke screen” and “curtains” convey this aspect of seclusion. The schools and streets enforce total assimilation to these rules and eradicate any alternate stances on how black people should live; they collaboratively create a situation where deviation from their strict directives threatens a black American’s life. Success in school equates to embracing the authenticity of the Dream and accepting the curriculum without question or protest, as this is the etiquette of “educated children” (25). Coates believes the “gift of study” is a necessary method to exposing the shackles acting on black Americans, since “a rapture” comes upon “[rejecting] the Dream” (116); such studies that utilize “courageous thinking and honest writing” (50) fail to comply with the school’s censored curriculum, and thus students would “be suspended and sent back to [the] streets” (33). School is the most efficient way to ensure that each new generation of black children adhere to thoughts and behaviors that support the Dream, as the classroom provides censored curriculum and intense supervision. Coates identifies how the trap uses both groups in tandem, since schools that are unable to make students conform proceed to funnel those defiant students into Baltimore’s streets.

These streets in question emphasize the intergalactic distance between the Dream and black reality, and encourage residents to abandon any hopes of escape and embrace “amoral and practical” (25) laws as necessary. In addition to independent study, Coates stresses how rapture exists in life beyond the aforementioned white suburbs. Coates’s wife is an example of how to seek change and benefit from travel. She refuses to restrict herself to living in proximity with Dreamers, since she “never felt quite at home” (117) in a society determined to belittle her. By travelling to Paris, she was able to see and experience how certain practices and ideologies “could be so common in one part of the world and totally absent in another” (119); desiring a change of scenery opened up “a gate to some other blue world” (121). When Coates follows her example and travels to France—a place he previously saw as belonging “in another galaxy” (26)—he learns how he has exaggerated the apparent chasm between himself and the country; lessening this perceived distance by physically changing his location allows him to momentarily experience life “outside of someone else’s dream” (124). While sitting in a French garden, he realizes that in America he “was part of an equation” (124) and that his change of scenery has allowed him to temporarily be freed from this constraint.

This possibility of venturing out and refusing to conform to another person’s dream is not entertained in Baltimore’s streets, as the pursuit of alternative futures would expose the environment’s true unpleasantness. Explaining the desire to leave the streets will reveal how Baltimore citizens’ eyes are “blindfolded by fear” (126), and how choosing to remain is submitting to the “generational chains [confining black people] to certain zones” (124). It has already been mentioned that the streets are a “zone” intentionally created by Dreamers, and that the violent and deadly characteristics of these zones should not be glorified. Exposing these fears—which have been artfully disguised in clothing and dark humor—would displease community members who are content with “a lifestyle of near-death experiences” (22). The dissonance created by exposing these harsh truths would likely lead to Coates being shot or silenced by force, since the ideas he proposes in order to escape these generational chains have been labelled as blasphemy by both the schools and the streets. The danger of the streets lies not only in those content to live in shrouded fear, but also in the actions of patrolling police officers. The hazard that police pose to black Americans is addressed in Between the World and Me, with Coates writing that the negative stereotypes against black Americans mean his son “must be responsible for the worst actions of other black bodies, which, somehow, will always be assigned to him” (71). The hands of prejudiced police or fear-driven gang members is what awaits students who refuse to abide by the school’s strict rules. The trap has been set: stay tough and content in the streets or risk being killed, and stay complacent and subdued in the schools or risk being sent back into the streets to be killed. These groups work together to regulate America’s systematic destruction of black bodies, since the only immunity from abuse and death lies within the mentality of these fabricated systems dedicated to preserving the Dream.

Despite success in school and descent into gang warfare appearing to be two distinct pathways within American society, Ta-Nehisi Coates reveals how he “came to see the streets and the schools as arms of the same beast” (33). Between the World and Me exposes both groups as manifestations of how America methodically oppresses black people, specifically by accentuating the power and prestige of those who believe they are white. Although his memoir details his personal life experiences, Coates recognizes that America contains “other Baltimores” (23) with the same problems addressed in this text. The early exposure and reinforcement of nationalistic pride towards the Dream encourages citizens to implicity accept that black people must suffer to preserve this fantasy. Disagreeing with this maltreatment is a direct threat to one’s body, and thus compliance and assimilation are fostered within the system at work. Coates is able to “unshackle [his] body” (21) and pursue his burning questions around black history, but such opportunities to escape America’s trap are rare. He encourages his son to follow his example and conduct personal research on how to survive as a black man in America, and makes it clear that attaining the freedom to do so will place him “among the survivors” (129).

Works Cited

Baltimore City Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. Baltimore City Gang Violence Reduction Plan. Governor’s Office of Crime Control and Prevention, 15 November 2006, www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-prevention-of-youth-viol ence/_pdfs/FINALGANGSTRATEGY.pdf. Accessed 20 March 2021.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. One World, 2015.