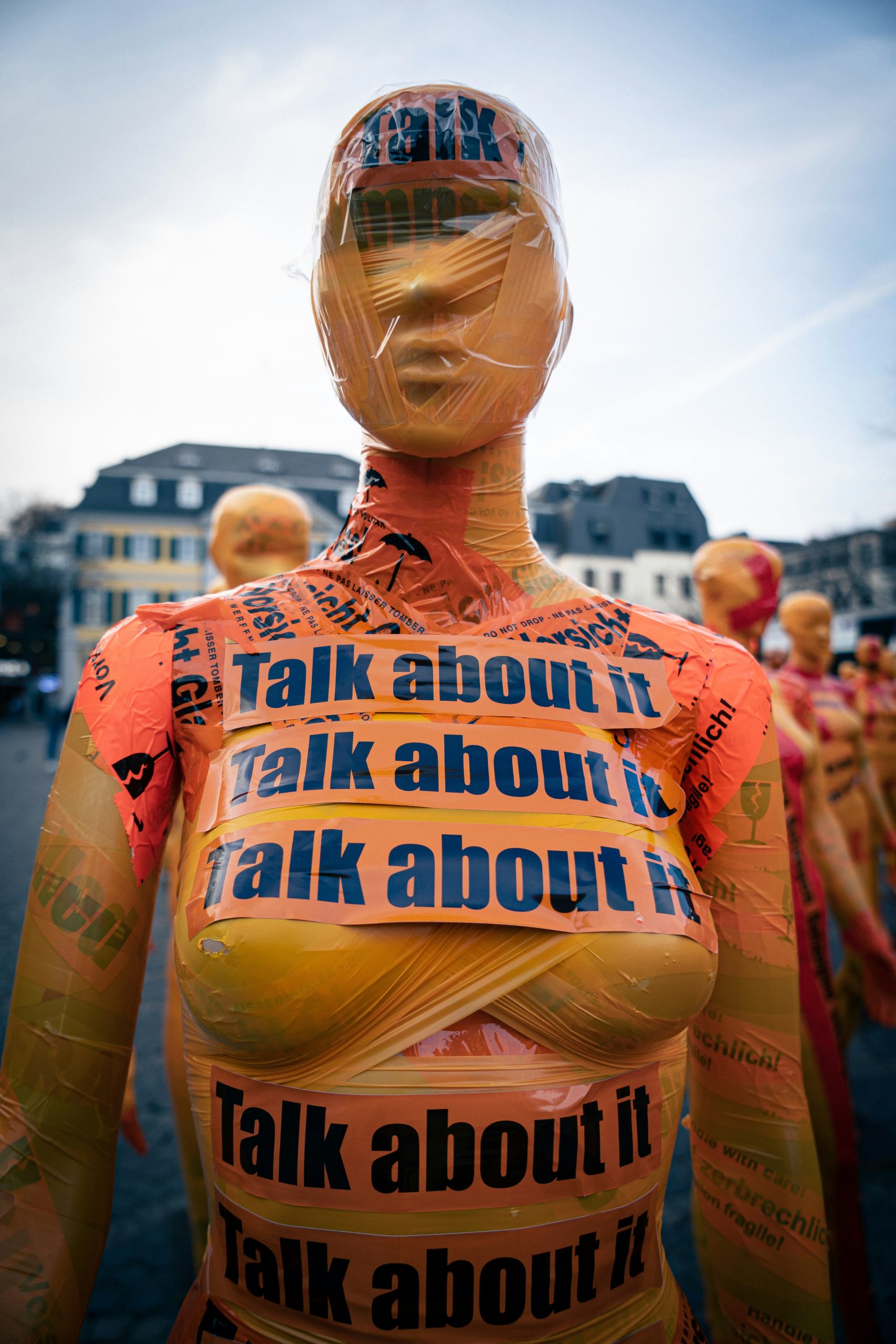

Photo by Mika Baumeister, via Unsplash.

by Noosha Shahriari

In “Gender culture in Hinduism, Traditionalist and Modernization issues”, A.V. Lutsenko states that “Women in classical Hin du texts [are] so often perceived as being of a lower order, sometimes reduced to Sudra level [the lowest of the social castes/classes], regardless of their actual caste. On the other hand, images of women [are depicted positively, in the position of] a variety of goddesses” (99). Women are valued in the Hinduism religion, but unlike their male counterparts, they are valued contextually rather than in their identity. The central scriptures of Hinduism, The Upaniṣads, translated by Patrick Olivelle bring attention to many ideas that are respected in modern spiritual and philosophical contexts. For example, they draw a focus on the spiritual concept of Oneness of the Self where “the Whole…becomes one’s very self” (30). This concept of individual connectedness between The Self and the elements of the world is prevalent and well-respected in many spiritual ideologies to this day (Garfield, Andrew M., et al). In light of this, its narratives may appear foreign to the academic reader. However, the text’s positive or seemingly ordinary ideals are convoluted with many harmful ones when it comes to sexual intimacy, desire, and gender inequality. Through the objectification and sexualization of both genders, the spiritual meaning of both male and female sexual bodies is portrayed as an integral theme within Hinduism. However, upon analyzing the portrayals and roles of men and women within theme of sexual imagery, the creation of women, reproduction and finally sexual intercourse, it is clear that a woman’s identity is far more objectified and sexualized than a man’s. Furthermore, in the few instances in which women are portrayed outside of sexual context, they only gain an authoritative voice after their selves are metaphorically distanced from the feminine identity. The Upanisad’s focus on masculine voices of authority and rejection of femininity in philosophical discussion pushes a narrative that women’s value is intrinsic to their sexual and reproductive abilities. This disparity between women and men is not specific to Hinduism, nor is inequality out of the ordinary for many religious texts of this datedness. Regardless, addressing the gender inequality in the Upanisad’s within the context of academia is crucial. Religious texts wield great authoritative value and the Upanisad’s themselves are central to many well-respected modern spiritual ideals and traditions. As such, it is not unlikely for one to take the entire text at face value, which could have dire consequences in the perception of gender at the individual, academic and even sociopolitical scale.

Throughout the Upanisad’s, graphic diction accompanied by sexual imagery is utilised to portray women and men unequally. One of the first instances of this may be seen when Gautama, an individual of the Brahmin class, asks the king of Pancala to teach him. The king goes about this by comparing many things to fire, including ‘man’ and ‘woman’ (using these terms to generalise all men and all women respectively). Fire is a symbolic and sacred element in Hinduism and the Upaniṣad’s and therefore this comparison establishes the spiritual significance of the male and female bodies, dictating their identity through their connection to the flame. The king states that man is fire, elaborating that “[h]is firewood is his speech; his smoke is breath; his flame is the tongue; his embers are sight; and his sparks are hearing. In that very fire gods offer food, and from that offering springs semen” (141). In this metaphorical comparison between the components of fire to that of man, the King acknowledges sexual attributes; however, his emphasis is on the senses. Attributes such as speech, breath, sight and hearing overshadow the more sexual attributes such as the (tongue and) semen. This portrays men as dynamic and layered individuals by establishing them as creatures who speak, see, listen, and also partake in physical desires. In conclusion, this passage highlights the spiritual importance of the male sexual body through its association with fire, whilst simultaneously portraying the gender as a whole through the inclusion of their senses outside of a sexual context.

Women, likewise men, are portrayed through the male-dominated voice of the scriptures (Lindquist 407). However, in contrast to their male counterparts, they are predominately depicted to be static, exclusively sexual creatures. Whereas men are depicted as fully, well-rounded peoples, women are regarded primarily “within the context of male sexual activity” (xlix). When a woman is compared to fire, the king states that “[h]er firewood is the vulva; when she is asked to come close, that is her smoke, her flame is the vagina; when one penetrates her, that is her embers; and her sparks are the climax” (141). Here, graphic diction and sexual imagery are used to portray women as a whole through their sexual organs and abilities without the inclusion of any sensical or non-sexual physical attributes. Additionally, this passage details the perspective of a man’s intimate use for a woman “when she is asked to come close…when one penetrates her” (141). This objectifies and demeans women by associating their spiritual significance exclusively with the sexual validity they can offer their male counterparts. This is supported by Steven Lindquist’s analysis of the philosophical roles of women in the Upaniṣads, who states, “[The Brhadaranyaka Upaniṣads] was composed by and for men…to suit their own ends or ideas” (Lindquist 407). It is then comprehensible that the ways in which women are portrayed one-dimensionally, as though they have nothing to offer to the physical or spiritual world beyond being an object for the alleviation of male desire, is a testament to how their worth at the time was perceived by men. The Upaniṣads reinforce gender inequality, not only due to the graphic diction and imagery used to portray women, but also in the fact that the roles of women seem to be depicted only through the gaze of men. This creates a narrative in which the value of women is intrinsic to their sexual abilities, whereas men are valued as a whole. Furthermore, the comparison between woman, man, and fire is made by a king who is a royal and therefore holds a rhetorically authoritative voice. The ethos informing his statements in the text is likely to incline many readers to respect his ideals. As a result of this gender inequalities may be manifested or reinforced in some readers, especially in a society where misogyny and the sexualization of women are still more than prevalent. Both genders are sexually objectified and associated with spiritual meaning by the king in their comparison to fire. However, an imbalanced dynamic is created in which women are disrespected and objectified far more than men. Ultimately the text implies that a woman’s worth is measured exclusively in her sexual significance, while that of a man’s is established by his attributes as a whole.

The imbalance between men and women in objectification and sexual characterization is furthered through the narrative established as a result of the creation of ‘woman’ and the act of reproduction. The creation of the first woman is depicted at the beginning of the scriptures when they state that when the first man was alone he “found no pleasure at all… [and] he wanted a companion… So he split his body into two, giving rise to husband… and wife” (14). Here, the husband’s need for a woman is iterated, as it is stated that without her he finds “no pleasure at all”. She is demeaned in the process of her creation through the implication that she exists simply as an extension of man. Furthermore, she is depicted as a means for him to find pleasure and to fulfil his desires. The scriptures state that “from his very self [man] will produce whatever he desires” (17). These passages establish a narrative that man creates ‘woman’ for no reason other than to make his life pleasurable. She is not regarded as her own self but as an extension of a man. Women are further objectified and disrespected when ‘man’ copulates with ‘woman’ against her will, and afterwards takes full credit for the creation of all offspring.

He copulated with her, and from their union, human beings were born. She then thought to herself ‘After begetting me from his own body…how could he copulate with me? I know- I’ll hide myself.’ So she became a cow. But he became a bull and again copulated with her …In this way he created every male and female pair that exists…then it occurred to him: ‘ I alone am the creation, for I created all this’. (14)

Not only is the woman objectified and demeaned when her attempts to “hide” in avoidance of copulation are ignored, but she is also stripped of any credit when it comes to reproduction and creation, giving the man more importance and authority in this passage. This praises the non-consensual actions of man and awards him full credit for creation, ultimately objectifying and degrading the spiritual meaning of the female sexual body even though ‘woman’ is created and characterized exclusively through the acts of intercourse and reproduction. This theme is supported by Steven Lindquist’s analysis of caste and gender in the Upaniṣads.

The male in this context is put in a dominant position and intercourse focuses on his needs and desire…[In contrast,] woman is objectified as simply a body that explicitly serves to produce merit for the male. (Lindquist and Cohen 90)

In conclusion, the portrayals of creation and reproduction in the Upaniṣads objectify and demean women by implying that women exist as an extension of men to fulfill their desires and failing to give them any credit for the act of reproduction.

The consequences of sexual intercourse for men in comparison to women further identify the latter’s objectification and denouncement. The concept of intercourse is often represented positively and beneficially for men, but as negative and threatening, for women. In the second Upaniṣads, Prajapati, ‘the creator of creatures’ creates woman “as a base for…semen” (88) and encourages men to have intercourse with woman. He states that man who engages in intercourse with an understanding of the spiritual meaning of a woman’s sexual body that “Her vulva is the sacrificial ground [and] her public hair is the sacred grass…” (88), then he will “[obtain] as great a world as a man who performs a soma sacrifice” (88). Because the soma sacrifice is a symbolic Hindu ritual the comparison of a man’s act of informed sex to a soma sacrifice portrays man, and by extension his sexual body with great spiritual meaning. The text doubles down on the positive aspects of sex for men when it states that “when a man…has sex-… he sings the chants and performs the recitations…these are his gifts to the priests” (126). Here it is reinforced that by having sex men are doing a good deed, one that is equivalent to the spiritual chants, or a gift to the priests. Through the establishment of spiritual meaning within man’s sexual body in the act of sex, one may deduce that intercourse benefits men as they can satisfy their desires while practicing spirituality, ultimately leading them closer to a state of Braham. Ultimately, in addition to being characterized dynamically outside of a sexual context, men are also able to reap spiritual benefits from the fulfillment of sexual desire.

Unfortunately, the opposite case is true for women. Even though women are portrayed exclusively as sexually significant creatures, they are not able to reap spiritual benefits as a result of sexual acts unless they do it when their male counterparts deem fit, whether or not it is consensual. In the words of Lindquist, “woman is portrayed as an instrument for male action, desire, and progeny, whereas the male is portrayed as virile and in control” (Lindquist and Cohen, 90). This is made clear when Prajapati states that women do not hold the knowledge of their own sexual bodies, whereas men do: “A man…engages in sexual intercourse with this knowledge…The women, on the other hand…[do so]…without this knowledge” (88). He continues to imply that they are negatively impacted because of this, stating that “[m]any who [engage] in sexual intercourse without this knowledge, depart this world…deprived of merit” (88). Here it is made evident that women are unable to act on their sexual desires without being deprived of merit, as they lack the knowledge to do so, unlike men. This establishes a misogynistic inequality between the two genders, as the act of intercourse has a positive impact on men, but a negative one on women. This theme is both juxtaposed and intensified with a vivid encouragement that men should use force to partake in intercourse if they are not given consent. Prajapati states that should a woman “refuse to consent, [man] should bribe her. If she still refuses, he should beat her with a stick or with his fists and overpower her, saying: “I take away the splendour from you with my virility and splendour’. And she is sure to become bereft of splendour” (88-89). This passage forces women into a corner in which upon acting on sexual desire they are to be drained of merit, but upon refusing they will be subject to bribery and ultimately rape. However, it also states that if a woman “accedes to [man’s] wish”, as in consents upon his demand, “they are both sure to become full of splendour” (89). The accumulation of these quotes interprets that if a woman has intercourse when a man demands it, even if she does not want to, then she will be rewarded. However, unlike her male counterparts, she lacks the understanding of her own spiritual body, as such she will be drained of merit if she herself decides to partake in the act. In conclusion, women face spiritually and physically harmful consequences resulting from sexual intercourse, whereas men benefit from the act, without being over-sexualized.

There are few depictions of “learned women” whose roles and validity exist outside of sexual contexts in the Upaniṣads. However, before they are depicted with authoritative voices in spiritual conversations, their identities are detached from the female gender as a whole. This implies that to be respected outside of a sexual context, women cannot be associated with femininity or womanhood. This can be seen in Gargi Vacaknavi’s etimologic masculinization and Maitreyī’s distancing from femininity. In many versions of the Upaniṣads, Gargi’s self is more timid in her speech with Yajnavalikia until she identifies “As a [warrior son]…stringing his unstring bow and taking two deadly arrows in his hand…[and demands] the answers…!” (Lindquist, 44). Lindquist states that “the composer of the text could have employed a gender-appropriate form, such as ugraputr ̄ı (‘‘daughter of a warrior’’), but chose not to. It is most likely that the author is attempting to make a point by choosing the masculine form” (419). By distancing Gargi from the feminine, she gains spiritual authority and can discuss and question Yajnavalikia boldly and effectively.

Gargi employs the…imagery of a male Ksatriya, positioning her above : the others present, at least in boldness. Gargi being ‘‘masculinized,’’ particularly in this hyperbolic sense, is an ‘‘emasculating’’ of the other Brahmins present. Gargi’s character is fashioned such that not only is she positioned above the other male priests, but also once again serves to position [Yajnavalikia] above them if he can answer her questions. Now, not only can [Yajnavalkia] out-talk the other Brahmins, he can metaphorically do battle with a male warrior. (Lindiquist 419)

It is only by appropriating maleness that Gargi is able to use “hyperbolic, unprecedented language…and…indicat[e] the importance of the questions that she is asking” to Yajnavalkia (Lindiquist 419). The only authoritative speakers such as Yajnavalikia himself in the scriptures are male, and there are few female inquirers in contrast to many men who are a part of the spiritual conversation. When they are present, they are separated from their gender identity, whereas men in spiritual conversations are accepted in their whole identity. In the case of

Maitreyī “she is contrasted with [Yajnavalkia’s] second wife who is defined as a person of “womanly knowledge”…”, indicating that Maitreyī’s intelligence exists outside of the typically female gender binary, and is for such reasons respected (Lindiquist 421). Such that the only two “learned women” (Lindiquist 421) who are a part of this discussion must be separated from their femininity is substantial, especially considering when a woman is depicted sexually in the scriptures, she is portraying the value of all women. Ultimately, women must be separated from femininity and womanness to gain spiritual value independent from their sexual and reproductive abilities. This restriction of the feminine in spiritual conversations further spotlights the significance of women not on their speech, inquiries or spiritual knowledge, but on their sexual and reproductive offerings.

The sexual bodies of men and women are assigned spiritual meaning through objectification and sexualization of their gender. However, upon analyzing the text’s inequality portrayed upon women in terms of sexual imagery and diction, their creation, the act of reproduction and the consequences of sexual intercourse, the Upaniṣads make it evident that men are viewed as spiritually whole, whereas women viewed in a sexual context. Even when women are given minute spiritual authority in the text it is only when they have been masculinized and connotatively separated from the feminine identity, which is evidently rooted predominately in sexual ability. Due to the dense and contradictory nature of the scriptures and the dense and contradictory nature of the modern world, there will be many perspectives on a text such as the Upaniṣads. The issue in this lies with the fact that the Upaniṣads is not a scripture with overall outdated ideals. Many of the ideas portrayed in the text continue to be praised, believed in and even viewed as “woke” to this day. Therefore when it comes to the text’s potential impact on readers and especially students the true meaning is irrelevant. Rather, it is the interpretation that shapes minds and ideas. Interpretation cannot be controlled, it is true, but it can be addressed, especially, when it comes to such sensitive topics such as physical assault and coercion are prevalent. The objectification, disrespect and over-sexualization of women in historical texts are unfortunately not unheard of, nor are they surprising. Left unaddressed, the convolution of these themes with those of a modernly accepted philosophical and spiritual nature creates a risk that readers will generalise all the aforementioned under either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Narratives of gender inequality and the sexual objectification of women continue to perpetuate systems and discourses of gender inequality in political and developmental policy making to this day. Without proper analysis of gender inequality in otherwise authoritative scriptures, their consumption in an academic environment may run the risk of negatively impacting readers of all genders, and reinforcing sexist ideals through the connotatively peaceful mask of spirituality. For this to be avoided, a conversation on these subjects must be initiated, no matter how uncomfortable it may be. For example, including a prompt of such nature would be beneficial to the initiation of such conversations. That is why I decided to write on this topic, even though there was not one seamlessly aligned with my topic. So, here is the prompt I would have liked to follow: “[T]he Upaniṣads we read for this week make extensive use of sexual imagery, including multiple references both to genitalia and to sexual intercourse… [Explain how these integrations are relevant to the inequality of gender in the text. Why is it important to address these narratives?]”. It is important because the objectification of women is still prevalent. Because the overshadowing of women’s voices is still prevalent. Because the over-sexualization of women is still prevalent. Because rape is still prevalent. Trigger warning, history repeats itself.

Works Cited

Garfield, Andrew M., et al. “The Oneness Beliefs Scale: Connecting Spirituality with Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 53, no. 2,

2014, pp. 356–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24644269. Accessed 24 Apr. 2024.

Lindquist, Steven E., and Signe Cohen. “Caste and Gender in the Upaniṣads.” The Social Background, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017, pp. 81–92.

Lindquist, Steven E. “Gender at Janaka’s Court: Women in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad Reconsidered.” Journal of Indian Philosophy, vol. 36, no. 3, 28 May 2008, pp. 405–426, doi:10.1007/s10781-008-9035-y.

Lutsenko, A. V. “The Role of Religious Factor in the Formation of Traditionalist Ideologies Opposing Violent Modernization.” Concept: Philosophy, Religion, Culture, vol. 4, no. 2, 31 July 2020, pp. 33–42, doi:10.24833/2541-8831-2020-2-14-33-42.

Upaniṣads. Trans. by Patrick Olivelle, Oxford University Press, 2008.