Photo via Flickr

by Johanna Clyne

Aphantasia is a condition where a person is unable to conjure images with their mind’s eye voluntarily. The phenomenon was first documented when Francis Galton described a trend among his colleagues, the vast majority of which claimed that “mental imagery was unknown to them” (Galton 302). The understanding of this phenomenon did not progress much after that until a study in 2015 found merit in Galton’s claims and that some people have been unable to conjure mental imagery since birth — a condition that they coined aphantasia (Zeman et al. 378). In 2019, I discovered this phenomenon and was blown away by the fact that some people live their lives with the ability to actually see things in their imaginations. As it turns out, I have lived with aphantasia all my life, and I simply did not know it.

Living with aphantasia may seem appalling to you if you have been visualizing for all your life; however, I do not know anything else. In my day-to-day life, I notice no difference between my imaginative ability and that of any other person. I do not see aphantasia as a condition to be cured or a disability to be pitied; I function just as well as anyone with the ability to visualize in almost every way. Almost. The place where I notice my imaginative abilities falling short is in comprehending visual descriptions of an object, place, or person that I have never seen before. Written descriptions of characters, scenery, and action scenes mean very little to me. I often skip what I can acknowledge intellectually as a beautiful passage of description because the stream of nouns and adjectives simply fails to conjure the desired images in my mind. Suffice it to say, ekphrasis is entirely lost on me.

In the 21st century, I can easily find reference images of the scenes that I fail to visualize. In reading Still Life with a Bridle, I had the luxury of searching the internet when I was unable to visualize for myself. The internet provides me with unlimited reference photos to understand the paintings that Herbert describes. I have no need for his descriptions to understand the artworks that he invokes. So his ekphrasis is useless, simple as that. Except, I don’t believe this to be true.

Ekphrasis functions not only to describe art but to imbue it with importance. While Herbert’s descriptions do not conjure up the image of these paintings before me, they give me a wealth of other important information. When reading of “old, intricate Gothic church towers above a group of fishermen, shepherds, and cows on the far shore of an imaginary landscape” (Herbert, 15), I inevitably fail to see the imaginary landscape, but Herbert is never merely describing a painting: he constantly provides guidance to his reader about what is important to notice in the frame, and pointing out the minute details that dramatically change how the painting is interpreted. Through ekphrasis, Herbert draws attention to the important aspects of the paintings in Still Life with a Bridle to the extent that, even for the aphantasic reader, the art can be appreciated in a non-visual medium.

In his description of Allegory of the Dutch Republic (117), Herbert offers physical descriptions paired with characterizing details. The first two sentences, containing the physical descriptions, are of very little use to an aphantasic reader. Being told that the model “has a country look: the pink cheeks of a shepherdess, round shoulders, [and] monumental legs firmly resting on the ground” (117) does not help me to conceptualize this painting beyond knowing facts about it that I could repeat. However, as the description continues, Herbert begins to guide the reader’s attention toward the details that are significant to him:

This is precisely what is most attractive in the painting: the contradiction between the elevated subject and its modest expression, as if a historical drama was played by a country troupe at a fair. The heroine of the scene does not resemble at all “Freedom leading people onto the barricades.” Soon she will leave the boring task of posing and go to her everyday, nonpathetic occupation in a stable or on a haystack (117).

For me, this passage is much more informative than the former because it is not describing what the painting looks like, but what Herbert sees in the painting. When originally looking at the painting, I did not notice the juxtaposition between the subject and her expression. My mind did not make the connection between an actor at a fair or a model that will soon return to her everyday life, but Herbert’s words bring this understanding of the painting into focus. In the context of the essay about the non-heroic subject, knowing that Herbert sees an actor or a model over the personification of victory or the glory of war drives home the essay’s message. Without having to visualize anything, Herbert’s ekphrasis expresses the significance of this painting to the essay.

Herbert’s description of Helena van der Schalke in his essay “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (68) similarly serves to draw our attention to certain aspects of the painting without the need to see or visualize the piece. For example, his description of the basket in her hand, which “destroys the static perpendicular axis of the composition [with] whirling movement, [and] restlessness” (68), gives the girl in the frame a life beyond the reach of the painting: we realize that the painting captures but a moment in the life of the small girl that Terborch endeavours to present, and that soon she will “run away to her inconceivable childish worlds” (68). Herbert again characterizes this painting as a living thing: “whenever I am in Amsterdam I visit and spend a few moments chatting with Helena van der Schalke” (68). Here, Herbert does not mention that Helena is contained in a painting and by using the term “chatting” we are influenced to think that Helena van der Schalke is capable of holding a conversation. These word choices set Helena up as someone beyond the frame of a painting and invite the reader to imagine the world that she lives in. In a way, seeing the frame around Helena traps her within the bounds of the painting. By relying on his ekphrasis to represent this painting Herbert creates a connection between reader and painting that would not be possible by simply looking at a picture on the page.

Herbert’s ekphrasis remains effective even when describing paintings that do not contain empathetic characters. In “The Nonheroic Subject” Herbert describes Hendrik Vroom’s Battle at Gibraltar on April 25, 1607 (116), in which ships collide and debris flies across the sky. In an essay about non-heroic subject matters, a battle scene seems out of place, however through his description, Herbert points out the non-heroism in this piece:

All this [is] seen as if through a telescope, from a distant perspective that dissolves horror and passion. A battle changed into a ballet, a colorful spectacle (116).

By pointing out that the scene is painted “as if through a telescope” (116) he changes the narrative that we tell ourselves when we imagine, or look at, this painting. Instead of a dramatic and heroic scene of war, we see a distant explosion, seen from the safety of shore. This shift in perspective gives scope to the viewer; we are no longer directly in the drama of the conflict, but sitting back and considering the scene rendered before us. The perspective removes any immediacy from the piece and encourages contemplation of how the themes of the essay apply to the painting. Herbert’s description removes the gravity of the piece and points out the distance and intricacy of the entire scene tying it into the theme of the non-heroic subject.

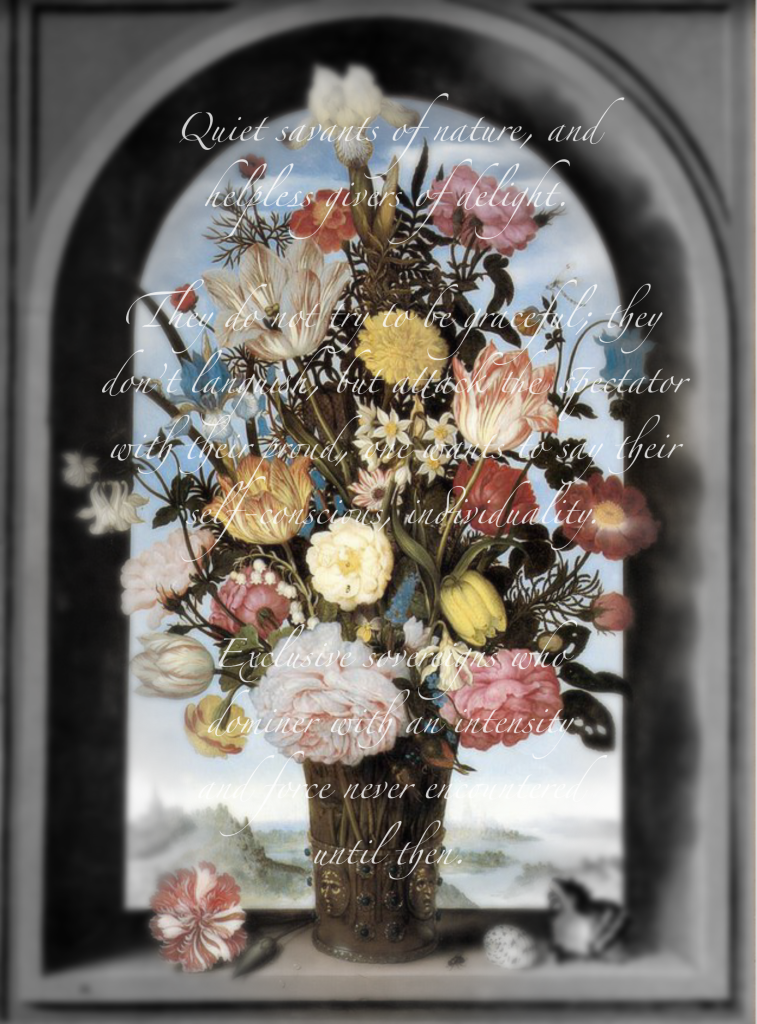

By describing the paintings of this text, Herbert is, significantly, not showing us these works of art. This is a frustrating choice for the aphantasic reader; just as easily as he describes “the flowers in this painting — quiet savants of nature, and helpless givers of delight — flaunt[ing] themselves” (40-41) he could have included a picture of Bouquet against a Vaulted Window. That he chose not to do this, and instead described each piece in detail, tells us that there is significance in the descriptions that he offers. Through his uses of ekphrasis, Herbert paints us a new picture in the place of those that he is referencing — one where the colours of the flowers do not matter so much as knowing that they are “exclusive sovereigns who domineer with an intensity and force never encountered until then” (41). For someone with aphantasia, this new painting is much easier to conceptualize because it does not matter what the painting looks like, so much as it matters that you understand the significance of the image that he creates with his words.

Ekphrasis proves efficient in creating a connection between the reader and the art that Herbert invokes. While the physical descriptions that he writes do not necessarily help the reader to know the work better, the way that he describes details of the artworks, like the swinging of a basket, the passing expression of a model, the distanced perspective of a tragedy of war, or the domineering presence of a bouquet, brings out the character captured in these works. For even the aphantasic reader, the characterization that Herbert brings through his descriptions of these paintings is far easier to understand than a picture on a page left up for interpretation. By guiding the reader through the process of engaging with these paintings, Herbert ensures that the elements that he relies on for his argument are noticed and understood. Though Herbert laments the difficulty of “translating the wonderful language of painting into the language… in which court verdicts and love novels are written” (97), he chooses to undertake the endeavour and does a wonderful job of giving meaning to these paintings through his use of ekphrasis.

Works Cited

Galton, F., 1880. “Statistics of Mental Imagery.” Mind 5(19), 301–318.

Herbert, Z., 1991. Still Life with a Bridle: Essays and Apocryphas, Toronto: Penguin Books.

Zeman, A., Dewar, M. and Della Sala, S., 2015. “Lives without imagery – congenital aphantasia.” Cortex 73, 378–380.