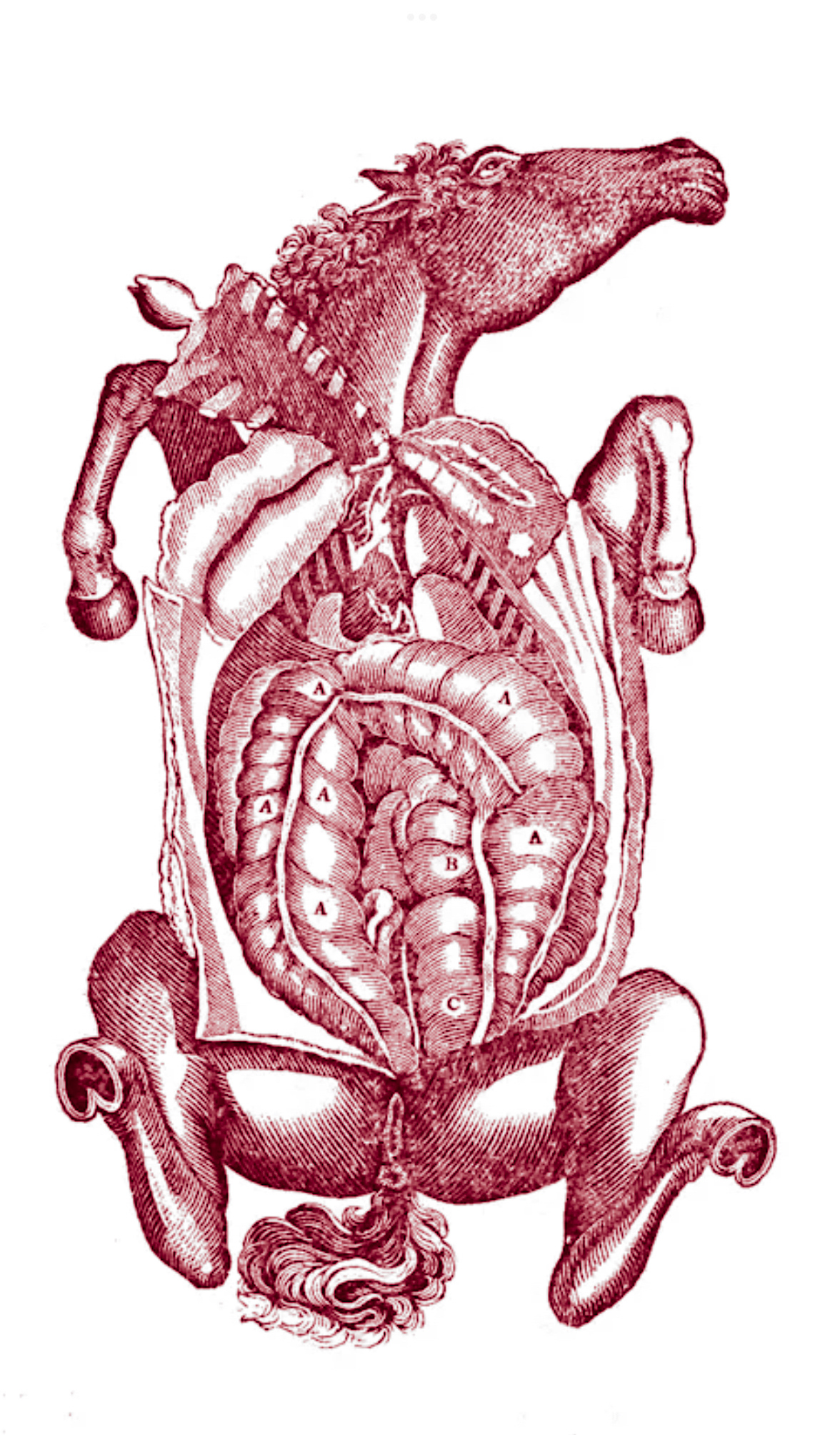

Image by William Carver.

by Lucas Rucchin

No geographical site seems to be more defined by myth than the U.S.-Mexico border. The extensive line of romantic cowboy novels, sensationalist television, and, most recently, rhetoric of Othering within the political landscape work together to shape the image of Mexico within the American cultural imagination. Breaking Bad, perhaps the definitive border fiction of our time, has given us the modern archetype of the evil Mexican and cartel mercenaries, who emerge in opposition to the American characters as quietly calculating, charismatically sadistic, and thoroughly un-American antagonists. Their mythology can be traced back to the era of Hollywood Westerns, which variously depicted ethnic Mexicans and Native Americans as a corruption for white gunslingers to rectify. Further back, we find border dynamics depicted with even slimmer sensitivity in cowboy dime novels and the vaudeville shows of Buffalo Bill. Still further, we find the historical backdrop of expansionism and settler colonialism, and finally, at the heart of the myth, the divine sanctioning of Manifest Destiny packaged up in the frontier dream.

It is easy to categorize Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses as yet another product of this mythology. In its most literal reading, the novel falls to all the tropes of border fiction. The reticent cowboy John Grady sets off on a journey into Mexico, where he encounters the thrill of nomadic adventure, an exotic love interest, and a sprawling, foreign country in need of taming. He confronts lawless Mexican foes, narrowly survives, and returns home in one piece. But the idylls of the novel belie its complexity. At its core, All the Pretty Horses is a deconstruction of Western mythology, in which the aspirational cowboy dream is evaluated and shown to be unattainable. In short, it is demythologized. Alone and without a ranch, riding out under a reddening sky, John Grady, newly weathered by the realities of Mexico, possesses nothing of the dream he once sought.

However, Cormac McCarthy is not interested in what his characters are thinking. By the end of All the Pretty Horses, John Grady has not explicitly reflected on where he intends to go, or how the mortal cost of his journey has affected him, or how his notion of the cowboy myth has changed. His thoughts, in the manner of the reticent cowboy, remain largely unexpressed. McCarthy’s stylistic power is instead devoted to the environment. Where we can locate John Grady’s mind—where we can trace the evolution of his cowboy dream as the events of his journey alternately propel, confuse, and dissolve the Western mythos—are indicated in the depictions of the grasslands, deserts, rivers, mountains, clouds, suns and moons of the rich and varied country he rides through. As Alan Cheuse notes, this is “more than a mere newly minted version of the romantic treatment of nature in fiction, in which landscape reflects the emotion of the characters” (174). What McCarthy embeds in his lands and skies is rather “an exterior version of the main characters’ inner universe” (174). John Grady’s inner universe is saturated with myth. He wants to reinvent himself in the image of the cowboy, which in the time of his story is merely a romantic cultural memory. Accordingly, McCarthy attunes the landscapes to respond to the condition of the myth, whether blossoming or slipping away within John Grady. Conducting a close reading of the landscapes in All the Pretty Horses therefore allows us to monitor McCarthy’s deconstruction of Western mythology in John Grady’s journey from America to Mexico, which is a journey from dream to disillusionment.

The novel begins with the death of a family member and the birth of a dream. John Grady is attending his grandfather’s funeral. A figure of the past, of the bygone world of cowboys, has been lost. From the beginning, the mythological reflections in the landscape are as clear as a passing train, like a revelation, which ruptures the solemn scene:

It came boring out of the east like some ribald satellite of the coming sun howling and bellowing in the distance and the long light of the headlamp running through the tangled mesquite brakes and creating out of the night the endless fenceline down the dead straight right of way and sucking it back again wire and post mile on mile into the darkness. (3)

In a kind of mechanical evocation of Manifest Destiny, the train sanctifies the landscape, illuminating the darkness, seeming to spawn civilization and order in the fences “creat[ed] out of the night”. The image calls attention to John Grady’s desire to move and, on some level, participate in the expansionist expeditions of his forebears. Bright and shuddering with speed, the train appears in juxtaposition to the grey tones of the funeral in what may be called “the death of Cole’s way of life” (Sickels and Oxby 348), a moment before his journey begins where John Grady realizes the inadequacy of his home life and, embodied in the image of the train, the allure of the mythical frontier.

Most of the landscapes at the beginning of the novel rely on this kind of juxtaposition between the colourless sense of alienation John Grady feels at home and the attraction of the cowboy dream coalescing within him. In the morning of the funeral, he stands “like a supplicant to the darkness” before the “thin grey reef beginning along the eastern rim of the world” (3). The greyness, which appears in several points of the novel as a marker of personal displacement, tells of his estrangement, not simply from a family that is passing on and away from him, but from the age of cowboys that modernity has made obsolete and which exists only in imagination. The reef-like clouds tell of the inexperience of his character, which he knows, and wants to mend. He is jagged, shapeless, performing the cowboy life without having lived it. Before he leaves for Mexico, John Grady experiences another period of estrangement in San Antonio, where he seeks out his mother for the final time. Their relationship is an apathetic one. His mother is distant from his father, himself, and his wish to own the family ranch, positioned as a barrier to the cowboy life and proof to John Grady that there is little left for him in a rapidly modernizing America. Appropriately, it snows during his time in San Antonio. Under a “grey and malignant sky” (20), snow falls on the landscape, turning the world at first white and translucent, and later on dark, cold and listless as he comes to terms with his mother’s indifference:

It grew dark early. He stood on the Commerce Street bridge and watched the snow vanish in the river. There was snow on the park cars and the traffic in the street by dark had slowed to nothing, a few cabs or trucks, headlights making slowly through the falling snow and passing in a soft rumble of tires. (20)

McCarthy writes the landscapes of San Antonio with such stark ennui that it is clear that John Grady does not belong here. The land tells of his alienation. He feels his family does not have any answers on “the way the world was” (21), and the coldness of his trip confirms it. As much as he searches for some belonging with his father and mother, he knows his home life has “nothing in it at all” (21). Such alienating greyness McCarthy contrasts with John Grady’s growing devotion to Western mythos. In the evening after the funeral, he rides under a sun that sits “blood red and elliptic under the reefs of bloodred clouds before him” (5). Historical memories of Native Americans seem to be embedded in the landscape, as the fiery sky triggers a stream of visions of Kiowa tribes: “painted ponies and the riders of a lost nation [coming] down out of the north with their faces chalked and their long hair plaited,” who are “redeemable in blood only,” who pass by him in a “ghost of nation” (5). The past endures in the landscape, and therefore riding through it allows John Grady to make sense of the Western mythos. As Ashley Bourne notes in “Plenty of Signs and Wonders to Make a Landscape,” McCarthy’s landscapes are “haunted by the echoes of violence and primitive history” and “constructed by shadows of events from the past” (119); in this instance they are haunted by the historical conflict between Native Americans and their colonizers. By positioning himself in the landscape, John Grady has also positioned himself in the past, where the mythologized “ghost” of America, in all its blood, horses, and tribal strife, seems to be very much alive. In effect, the landscape connects him to history, “a history larger and more extensive than [his] personal experience” (Bourne 121). Cheuse underlines this connection succinctly: “Having a map to the territory before you means having a past, both personal and historical, whose visions and outer signs you may easily read in order to find orientation” (216). John Grady finds orientation in a landscape where the Western mythos can be reproduced, allowing him to escape his home life of rootlessness and discover a sense of personal fulfilment in a cowboy life of his own making.

The estrangement John Grady feels at home, coupled with the devotion he feels to the past, motivate his decision to cross the border, as he and Rawlins soon after agree to begin their journey to Mexico. In their decisive conversation, the stars are “falling down the long black slope of the firmament” (26). The imagining of a physical landscape in the sky, of stars in motion on hills, tells of his drive for movement, so fundamental to the cowboy mythos. When they finally depart, the stars are “swarming” in the “tenantless” sky (30), recalling the American expansion westward and the claim of territory. The sky is a “dark electric, […] a glowing orchard” (30), which evokes the colonial undertones of their journey: the civilizing element of electricity and the idea of the frontiersman as a bringer of light. “The landscape transforms itself to encompass their experience” (Bourne 34), that experience being their final commitment to reinventing themselves as cowboys. Aspects of the mythos radiate in John Grady’s mind as his journey begins.

Crossing over into Mexico, John Grady encounters the wild, primitive landscapes he wished for. Untouched by modernization, the country is as beautiful as it is “barren,” “desolate” and “still” (51), as he and Rawlins set out across green plains under a blue sky. A ghostly characterization of the terrain through the eyes of the aspiring cowboys reinforces the landscape’s connection to the past: “the mountains of Mexico […] [drift] in and out of cloud-cover like ghosts of mountains” (42), and rainclouds move behind them “like some phantom migration” (69). Later in the night, after John Grady hears wolves howling, the landscapes demonize themselves: the moon appears “cocked over the heel of the mountains” like a weapon, and the dawn becomes a “false blue dawn” which is “dragging all the stars away,” including the constellations of “Orison and Cepella and the signature of Casiopea,” icons that he hangs onto for familiarity in this suddenly unknown, hostile, and “wild” land (60). As conflict arises, the landscapes take on malignant forms. Consider the lightning storm that terrorizes and runs the characters into shelter:

Shrouded in the black thunderheads the distant lighting glowed mutely like welding seen through foundry smoke. As if repairs were under way at some flawed place in the iron dark of the world. (67)

Beautiful, uninhabited, and sometimes dangerous, Mexico fulfills John Grady’s nomadic desires. “The life of the cowboy,” according to Bourne, must be “attuned to the weather, the livestock, and the land, riding miles of open country” (Bourne 121). But there is also a brutality present in the country that John Grady is reluctant to acknowledge, as it suggests that a certain ruthlessness shadows their mythological journey.

Further south, John Grady arrives at the “Hacienda de Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción, a ranch of eleven thousand hectares situated along the edge of the Bolson de

Cuatro Cienegas in the state of Coahuila” (97). In “The Cost of Dreams of Utopia: Neocolonialism in Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo and Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses,” Susan Lee observes how John Grady “uses the Mexican landscape to alleviate his disillusionment with American society,” and in doing so “unknowingly becomes the colonizer” (153). Through his mythological gaze, he “believes he has found a utopian landscape” that is “perfect for his recreation of the frontier myth” (152). Indeed, John Grady actualizes the Western mythos on the ranch. It is idyllic, lush and well-kept, “well watered with natural springs and clear streams and dotted with marshes and shallows lakes or lagunas” (97). It emerges from the lightning storm “in a deep violet haze” under “red galleries [of] cloudbanks” (93), and seems possessed of a perfect, “golden” lifestyle (93). He tames wild horses, and does it so impressively that his work attracts a crowd. He is respected for his knowledge and is even consulted by the owner of the ranch for his opinions. He goes with Rawlins into the mountains to find horses. He goes to the dancing hall to find love. In Alejandra he discovers not only the most intimate of connections but also the chance of owning “the spread”: the possibility of remaining a cowboy for his entire life. One night, under the stars, he is taken in a moment of silent catharsis:

He lay looking up at the stars in their places and the hot belt of matter that ran the chord of the dark vault overhead and he put his hands on the ground at either side of him and pressed them against the earth and in that coldly burning canopy of black he slowly turned dead centre to the world, all of it taut and trembling and moving enormous and alive under his hands. (119)

As the ranch represents the apparent fulfillment of John Grady’s dream, the landscape responds to that fulfillment. Here we have the emphasis of stars “in their places,” in the way that John Grady has found belonging in a place that corresponds with his desires; the “belt of matter” that is “hot” and “burning” in the way of his passion for Alejandra; the “dark vault” of the sky evoking the ceiling of a church, as though he is in a silent prayer of gratitude for his situation; and finally the landscape “under his hands” in a suggestion of control, as his mythological vision of the landscape affords him a kind of power to “mold his surroundings in order to attain his mythical and idealized frontier” (Lee 163), which he channels to dominate the region in pursuit of his dream.

John Grady’s time on the ranch is short-lived, as his indulgence in a contrived and romanticized lifestyle eventually causes its disintegration. His pursuit of a relationship with Alejandra and his disobedience of Alfonsa leads him to be “thrust out of this adopted landscape” because of “his inability to separate the romanticized vision of the place and the reality of social convention” (Bourne 121). Without the safety of the ranch, and by extension without the illusion of control over his mythological vision, the landscapes of Mexico return to their strange and hostile aspects. In the drive to the prison, lightning appears again in the landscape, reminding him of the ruthlessness of the country: “summer thunderheads were building to the north and Blevins was studying the horizon and watching the thin wires of lightning” (175). Strangeness haunts him: the car passes “feral cattle the colour of candlewax […] like alien principles” before it arrives “in the yard of an abandoned estancia” under the watch of “hawks […] in the upper limbs of a dead tree” (178), all of which culminates in Blevins’s execution. His death sobers their journey, as the mythos John Grady has followed to this point seems futile compared to its mortal consequences.

What follows is the dissolution of the myth. Released from prison, John Grady returns to the ranch to find “the countryside much changed, the summer past” (222); the landscape no longer glows with the same utopian life. In his final attempt to preserve the myth, John Grady seeks out Alejandra. When she rejects his offer of marriage, the last foundation of his cowboy life crumbles. He is left alone and without a ranch. Once again he inhabits the role of the outcast that he did back home in the world of faded fathers and absent mothers. He sees “very clearly how all his life led only to this moment and all after led nowhere at all” (254). The landscape returns to a cold greyness: “a fine rain” falls in the town where he is deserted, and like the snow of San Antonio, it reflects his estrangement. Later on, when John Grady is camped out in the wilderness, McCarthy draws the landscape with a distinct hopelessness: he listens to the “wind in the emptiness” and watches the stars “trace the arc of the hemisphere and die in the darkness” (256). Hunting and killing a doe lead him to perhaps his most revelatory moment, as landscape and mind converge to lay bare everything that John Grady has learned:

The sky was dark and a cold wind ran through the bajada and in the dying light a cold blue cast had turned the doe’s eyes to but one thing more of things she lay among in that darkening landscape. […] He thought that in the beauty of the world there hid a terrible secret. He thought the world’s heart beat at some terrible cost and that the world’s pain and its beauty moved in a relationship of diverting equity and that in this headlong deficit the blood of multitudes may ultimately be exacted for the vision of a single flower. (282)

Cold and alienated, he realizes the failings of his journey: that he could not temper myth with reality, and that the pursuit of a single mythological vision cost him the lives of so many.

At the end of the novel, as John Grady rides into the desert, the bloodred sky is invoked repeatedly. However, it does not signify the fervor for the mythological it did in the beginning of his journey. The figure of the cowboy has been demythologized. He has lived the reality of Mexico and has emerged disillusioned. As he and his horse’s shadow merge, he becomes no longer the performance or the dream of a cowboy but a cowboy of his own. McCarthy mirrors the very same landscape at the beginning of the novel—the redness, the sun coppering his face, and the wind blowing down into the landscape—to illustrate the full circle of John Grady’s character, who begins by crossing into Mexico inexperienced and ends by crossing into Mexico experienced, who begins with an aspiration for Western mythos and ends with a reality of bloodshed and grave mortal cost. He has accepted his role as outcast, relinquishing himself to the world, not to the “ten-thousand worlds for the choosing” of myth (30), but what is real and imminent, the “world to come” (301).

John Grady’s journey into Mexico is rooted in a romanticized perception of Western mythology rather than the actual country he traverses. Mexico and its landscapes function not as a site of genuine cultural appreciation but rather as a mechanism through which he represses his disillusionment with the alienation of his home life and American modernization. Not so much a backdrop as a narrative and thematic guide, the landscapes of All the Pretty Horses map out the condition of the Western mythos in John Grady’s mind, which begins in romantic colours and progresses into sobering forms as the dream is unraveled, as the cowboy is desanctified, and as the mythology is revealed for what it truly is—myth.

Works Cited

Bourne, Ashley. “‘Plenty of Signs and Wonders to Make a Landscape’: Space, Place, and Identity in Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy.” Western American Literature, vol. 44, no. 2, 2009, pp. 108–25. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43022719.

Cheuse, Alan. “A Note on Landscape in All the Pretty Horses.” The Southern Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 4, 1992, p. 1401.

Lee, Susan. “The Cost of Dreams of Utopia: Neocolonialism in Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo and Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses.” Confluencia, vol. 30, no. 1, Fall 2014,

pp. 152–170.

McCarthy, Cormac. All the Pretty Horses. Vintage Press, 1992.

Sickels, Robert C., and Marc Oxoby. “In Search of a Further Frontier: Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, vol. 43, no. 4, 2002, pp.

347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00111610209602189.