Frantz Fanon, by Pacha J. Willka, Wikimedia Commons, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0

by Moneeza Badat

In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon enhances a Marxist analysis by addressing the intersections of race, colonialism and capitalism. Fanon uses the terminology of Marx and Engels but applies it in different ways. By ‘stretching’ Marxist analysis, Fanon makes it relevant to decolonization (Fanon, 5). Though Marxism provides a competent analysis of capitalism, it does not fully address the intersections of race and colonialism. Fanon’s modification of Marxist analysis results in a more comprehensive Marxism. Fanon regards the peasants and proletariat in a strikingly different way from how Marx and Engels regard these groups in The Communist Manifesto. Though in the Manifesto, Marx and Engels discuss how the power of rebellion lies with the proletariat, Fanon is critical of the proletariat in the colonized nation and sees the power of rebellion lying with the peasants (Marx and Engels, 94). The power of rebellion that lies in the hands of the peasants in the colonized nation could be attributed to the presence of Islam in the rural masses, although Fanon himself does not explicitly argue this. Both Marx and Engels see the potential in religion as a revolutionary force. Fanon stretches and enhances Marxist analysis to address the intersections of capitalism, colonialism, and race in what might be called his ‘decolonization manifesto.’

Fanon ‘stretches’ Marxism by addressing the internalized colonialism and capitalism of the ‘national bourgeoisie.’ With the term colonized nation, Fanon does not refer only to the land and territory that is colonized but also to the colonized mind. Fanon must expand Marxism because the Manifesto does not explicitly address the intersections of racial oppression with colonialism and capitalism. Fanon is critical of the national bourgeoisie of the colonized country and sees them as imitating their counterpart in the West

…because on a psychological level [the national bourgeoisie] identifies with the Western bourgeoisie from which it has slurped every lesson. It mimics the Western bourgeoisie in its negative and decadent aspects without having accomplished the initial phases of exploration and inventions that are the assets of this Western bourgeois whatever the circumstances. (Fanon, 101)

What bothers Fanon is that the national bourgeoisie have no merit of their own and only imitate the Western bourgeoisie. The national bourgeoisie simply want to take the place of the bourgeois colonizer. Their desire to take the place of the Western exemplifies how the colonized have internalized racism and colonialism. This internalization is part of the psychological makeup of the colonized nation. Decolonization does not involve just reclaiming the land, but also decolonizing the mind.

Marx and Engels say something similar about the bourgeoisie in the Manifesto. The Manifesto discusses how the bourgeois expands across the globe into all nations and “compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In a word, it creates a world after its image” (Marx and Engels, 66). The expansion of bourgeois culture is exactly what occurs in the colonized nation in which the colonized peoples mimic the Western bourgeoisie. Fanon enhances the statement made in the Manifesto by addressing the internalized racism and colonialism of the colonized peoples. It is not the bourgeoisie who, solely by themselves, are trying to create “a world after its image.” Part of this expansion is encouraged or promoted by the colonized ‘national bourgeoisie’ who “mirror” the Western bourgeoisie because they want to take their place and become the colonizers.

Fanon and Marx come to different conclusions on the role of proletariat. Fanon is critical of the proletariat while the Manifesto is written for the proletariat whom Marx and Engels see as the revolutionary class. Fanon states that the proletariat in the colonized nation are, in essence, the bourgeoise:

It has been said many times that in colonial territories the proletariat is the kernel of the colonized people most pampered by the colonial regime. The embryonic urban proletariat is relatively privileged….In the colonized countries, the proletariat has everything to lose….These elements make up the most loyal clientele of the nationalist parties and by the privileged position they occupy in the colonial system represent the “bourgeois” fraction of the colonized population. (Fanon, 64)

Fanon explains that the proletariat has benefitted from colonization. The proletariat is “pampered by the colonial regime” and is not concerned with national liberation. Because the proletariat is benefitting from colonialism, it is not the revolutionary class. This argument could not differ more from that of the Manifesto:

Of all classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class. The other classes decay under the presence of big industry; the proletariat is its very own product. (Marx and Engels, 72)

The inverted roles of the proletariat in the Manifesto and The Wretched of the Earth are due to historical and geographical context. The proletariat in the industrialized country is exploited. In the colonized nation, the proletariat run the “colonial machine” (Fanon, 64). The proletariat in the colonized nation is not the revolutionary class for it has no need for or interest in being revolutionary insofar as it is benefiting from colonization.

Where Marx saw the power of rebellion resting with the proletarians, Fanon sees it resting in the hands of the peasants, the rural mass, and the villagers, many or most of whom are Muslims. Fanon explains the reason that the peasants are often brushed aside in revolution:

The Westernized element’s feelings towards the peasant masses recall those found among the proletariat in the industrialized nations. The history of bourgeois revolutions and the history of proletarian revolutions have demonstrated that the peasant masses often represent a curb on revolution. In the industrialized countries the peasant masses are generally the least politically conscious, the least organized as well as the most anarchistic elements. They are characterized by a series of features…defining an objectively reactionary behaviour. (Fanon, 66)

Fanon describes the doubt felt towards the peasants as a “Western” attitude among industrialized nations where peasants are not “politically conscious”. Rather, they are defined as “reactionary.” This is the same characterization that Marx and Engels give of the peasants: “They are therefore not revolutionary, but conservative. Nay more, they are reactionary, for they try to roll back the wheel of history (Marx and Engels, 72).” Marx and Engels call the peasants the reactionary class and Fanon recognizes this attribution as a “Westernized” element. The Manifesto states that the lumpenproletariat, which may include the peasants in both an industrial and colonial context, may be involved in revolution, but the primary role is in the hands of the proletariat. Meanwhile Fanon sees the peasants as “the only spontaneously revolutionary force in the country” (Fanon, 76). Fanon does not disagree with Marxism, he simply interprets it to make it applicable to the colonized country.

The power of rebellion may rest in the hands of the peasants because of the heavy presence of Islam in the rural masses, which Fanon does not elaborate on. Fanon makes it clear that power is with the peasants and lumpenproletariat––that is, ‘the wretched of the earth’–– but does not explain how he comes to this distinction by drawing from Marxism. Fouzi Slisli provides an explanation of why the peasants are the revolutionary class in the colonized nation:

The careful reader can discern that [Fanon] makes constant references to Islam without acknowledgement. He says, for example that ‘the memory of the anti-colonial period is very much alive in the villages.’ Did he know that Algeria’s anti-colonial tradition in the nineteenth and early twentieth century was mobilized and organized by Islamic Sufi brotherhoods in the name of jihad against occupation? (Slisli, 103)

The answer to Slisli’s question is certainly ‘yes’, but the question is why Fanon did not elaborate on the connection between anti-colonialism and Islam. Slisli fills the gap Fanon leaves concerning why the peasants are revolutionary. While Fanon’s position on Islam is unclear in the book, Marx says that religion is the ‘opium of the people.’ Marx may be saying that religion has two functions insofar as it can be compared to a drug. It can be abused like a hallucinogenic to distract people from capitalism and the bourgeoisie with illusions of the otherworldly. However, used for its medicinal function, opiate also heals, nourishes, and inspires the people. Religion, the opiate of the people, can be abused or used to heal them. Fanon could be seeing the latter potential of religion in the rural masses. Instead of distracting the peasants from the condition of colonization around them, they are fueled to fight against colonization.

Though Fanon does not say if and how Islam inspires revolutionary thoughts or actions among the peasants, it is possible that Islam would provide the peasants with the intellectual, cultural and political tools to resist colonization. Marx and Engels discuss how the proletariat, who in the industrialized nation are the “lowest” of rank, must blow up the superstructure of society: “The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot raise itself up, cannot stand up straight, without exploding the whole stratified superstructure of official society (Marx and Engels, 73).” If “proletariat” is replaced with “peasant”, the passage from the Manifesto becomes relevant to the revolutionary movement of decolonization. Following Slisli, Islam may provide the tools needed for the peasant to blow up the colonial “superstructure.”

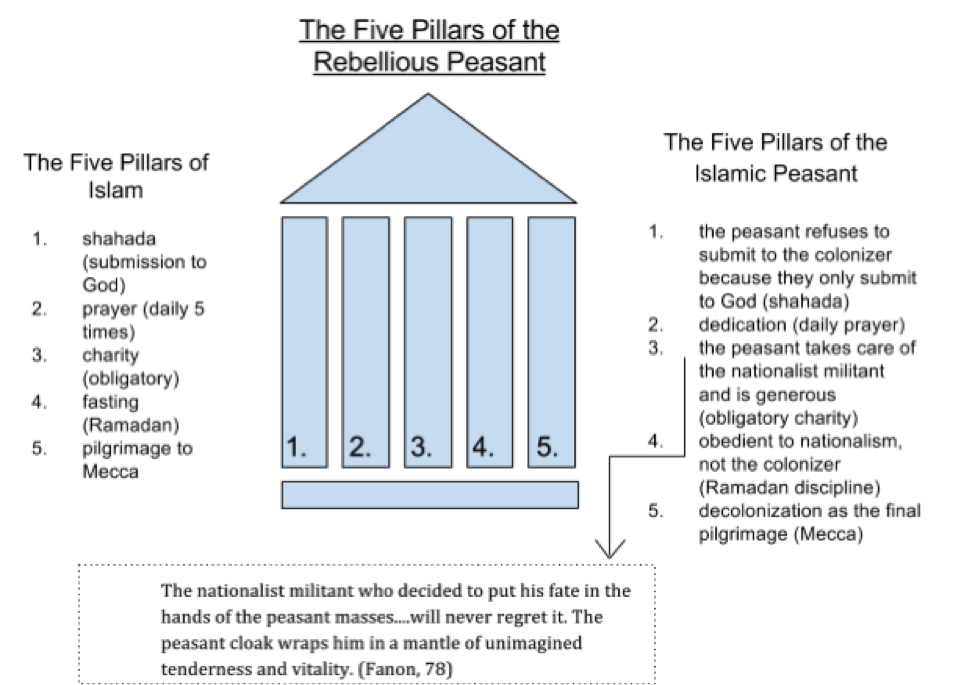

From its foundation in the five pillars of faith, Islam can provide the peasants with the tools to defy colonization and to take part in decolonization. From the shahada, the first pillar of faith in Islam in which Muslims profess that ‘There is no god but God’, the peasant cannot submit to the colonizer or the West as he only submits to God. The daily prayer gives the peasant dedication. The obligatory charity makes him generous, as Fanon remarks (see Fanon, 78 above). The last pillar of faith, the pilgrimage to Mecca, can be understood as the last act that the peasant undergoes: the act of decolonization. The five pillars of faith are tools that allow the peasants to destroy the colonial superstructure and in effect may be what makes them revolutionary. Marx was ambivalent about religion but saw its revolutionary potential. Perhaps Fanon does not elaborate on religion because of his own uncertainties. However there is another intersection at play: the intersection of religion and decolonization. Fanon does not elaborate on this intersection. As Slisli points out, religion would be able to fuel the revolutionary class. Both Marx and Fanon seemed to see religion’s revolutionary potential.

Fanon enhances Marxism to make it applicable for the colonized nation. Marx and Engels say that the bourgeoisie move across the globe and spread everywhere. Fanon takes this argument further by addressing the role of internalized racism in the colonized people in this expansion. The discernable difference between the Communist Manifesto and The Wretched of the Earth is the role of the proletariat and peasant. The Manifesto is written to inspire the proletariat as the revolutionary class, while urging them to fight against the bourgeoisie. The peasants are not pivotal for Marx and Engels. Fanon, by contrast, sees the proletariat as the bourgeoisie of the colonized nation and the peasants as the revolutionary class. The potential of the peasants may be attributed to religion, which is something that Fanon and Marx both remain ambivalent about. The Manifesto is a call to action––“Proletarians of all lands unite!” (Marx and Engels, 94). So too is The Wretched of the Earth––“Now, comrades, now is the time to decide to change sides” (Fanon, 235). The Wretched of the Earth and the Manifesto are fighting for the same cause, in a sense. They both want to destroy the superstructure of capitalism and colonialism through a movement originating from the substructure. Each book is simply addressing the class that has the most potential to destroy each superstructure. In this way, The Wretched of the Earth can be understood as another type of manifesto: the Decolonization Manifesto.

References:

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Preface by Jean-Paul Sartre. Richard Philcox trans. New York: Grove Press, 2005.

Marx, Karl, and Joseph J. O’Malley. Critique of Hegel’s ‘Philosophy of Right’ Cambridge: U, 1970. Print.

Marx, Karl, Friedrich Engels. The Communist Manifesto. L. M. Finlay trans. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 2004.

Slisli, Fouzi. “Islam: The Elephant in Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth.”Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies (2008): 97-107.